Key in a search term below to search our website.

Key in a search term below to search our website.

This historic Bruce-Oosterwijck pendulum sea clock played an important role in the long quest for a practical way of determining longitude at sea; a problem that made sea voyages incredibly hazardous.

Date

1662

Made by

Severyn Oosterwijck (c.1637- c.1694)

Made in

The Hague, the Netherlands

Made from

Brass

Dimensions

17cm x 13.5cm x 7cm

Acquired

The acquisition has been made possible by the National Heritage Memorial Fund (NHMF) and Art Fund.

Museum reference

T.2018.215

On display

The clock is on display in the Earth in Space gallery at the National Museum of Scotland.

Did you know?

In 1714, a prize was offered to anyone who could find a way of successfully calculating longitude at sea. The fame of this prize continues to the present day, with the Longitude Prize offered to tackle growing levels of antimicrobial resistance.

“…nothing is so much wanted and desired at sea, as the discovery of the longitude, for the safety and quickness of voyages, the preservation of ships, and the lives of men…- Longitude Act, 1714

Above: The Bruce-Oosterwijck longitude pendulum clock.

Made in 1662, the clock was part of the first attempt to establish longitude at sea with a purpose-made mechanical timepiece. While latitude (the north-south position of a point on the Earth's surface) could be worked out by observing the height of the sun or stars above the horizon, longitude (the east-west position) was harder to ascertain.

The ‘longitude problem’ is famous as an exemplar of scientific endeavour with a truly global effect, however, the early Scottish contribution is less well-known.

Alexander Bruce, Earl of Kincardine commissioned the mechanism for this clock from the Dutch maker Severyn Oosterwijck in 1662. Bruce lived in the Netherlands as part of the Stuart court in exile and was one of the founder members of the Royal Society.

Oosterwijck (c.1637- c.1694) was a leading clockmaker and craftsman of the Dutch golden age who played a key part in the birth of the pendulum clock. He became the first Master of the Hague Clockmaker’s guild, having been one of the petitioners for its incorporation.

Above: Alexander Bruce by Jan Mytens c1660. © Broomhall Home Farm Partnership.

As the Earth rotates, different places on the globe experience different times. Sunrise comes first to Moscow, then Edinburgh, then New York. On a smaller scale, sunrise (and noon, and sunset) comes just over four minutes earlier in Edinburgh than in Glasgow to its west. If you have a clock which was set to the exact sun time in one place and it keeps accurate time as you carry it somewhere else, you can work out how far east or west you have travelled. The difference between the local time from the sun where you are, and the time at your reference location gives the longitude.

To use this method to work out longitude at sea required a clock that would keep accurate time on board a ship, in humid conditions on a pitching and tossing sea. In the 17th century, this was easier said than done.

Knowing your latitude and longitude at sea is not enough for good navigation – it is also vital to know where the ports and dangerous rocks are, which requires accurate maps. British expertise in mapping led to the worldwide adoption of Greenwich Meridian (the North-South line through the Royal Observatory, Greenwich, London) as the universal zero for longitude in 1884. Longitude was therefore calculated by working out the time difference between your location and Greenwich Mean Time.

The first practical pendulum clock was invented in 1656 by the Dutch mathematician and astronomer Christiaan Huygens (1629–95). He then turned his attention to the creation of an accurate sea clock for the determination of longitude.

Huygens collaborated with Bruce on the project, with the Scot introducing a number of new features to the Dutchman's designs before having four sea clocks made, two of them by Severyn Oosterwijck.

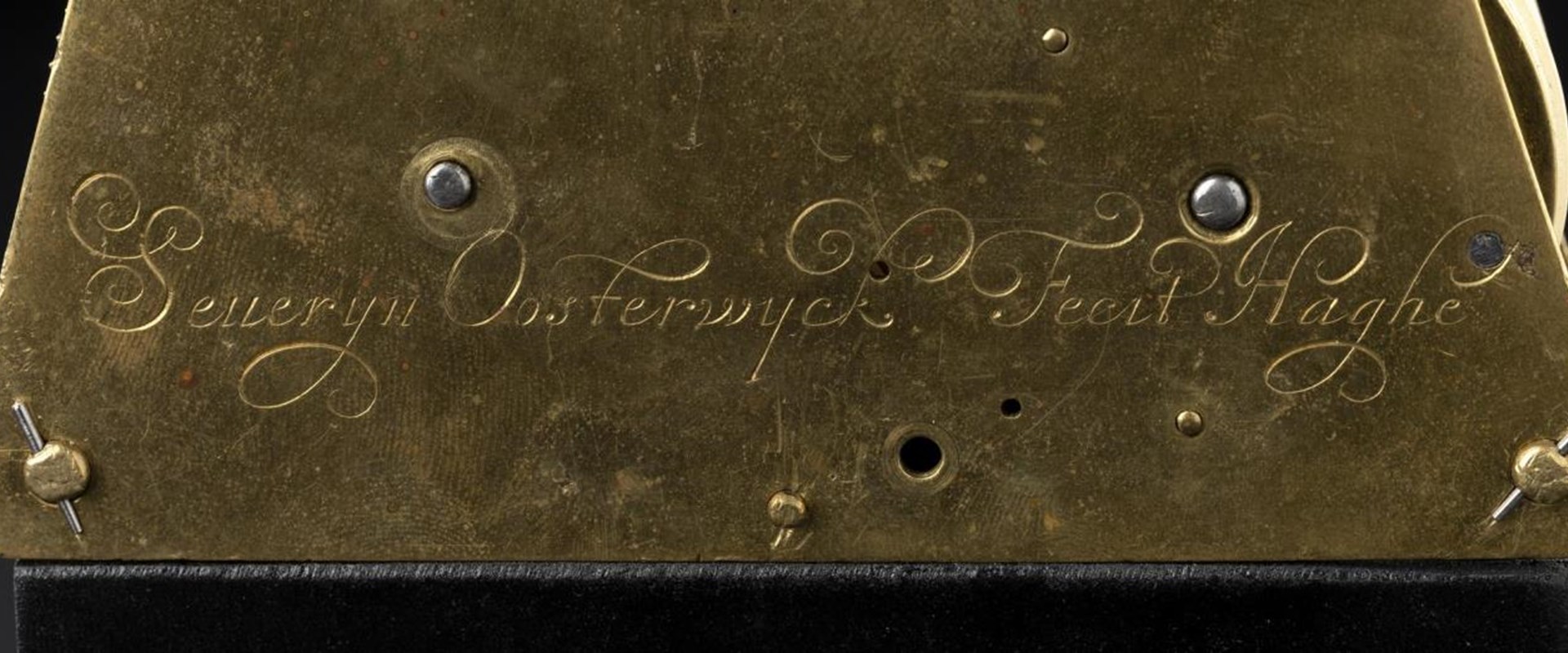

Signature of Severyn Oosterwijck on the Bruce-Oosterwijck longitude pendulum clock.

By the end of 1662, Bruce’s initial sea-trials were proving promising. More formal sea-trials were carried out, with reports suggesting that the clocks had performed exceptionally well.

However, these reports eventually proved to be inaccurate. Captain Robert Holmes, who had been entrusted with the trials of the clocks (though his attention was clearly more devoted to plundering Dutch merchant shipping), had reported implausible success beyond even the best hopes for the clocks. Samuel Pepys was asked to investigate, and it transpired that the glowing reports were entirely fictitious. Despite the optimism of the 1660s and extensive discussions over patents and profits, the new marine timekeepers turned out not to be the solution that had been hoped for.

It was another century before the English clockmaker John Harrison would famously solve the longitude problem.

After its sea trials in the 1660s, Bruce's clock was converted into a domestic clock and disappeared from the historical record. There is no knowledge of its whereabouts between c.1670 and 1972; it appears its interest was forgotten, and it was accepted as a later 17th-century domestic clock, though still of considerable importance for its date, maker and quality of craftsmanship. It owes its survival to serving as a working clock over the centuries and has only recently been recognised for its role in the quest for longitude.

Above: Senior Curator Tacye Phillipson with the Bruce-Oosterwijck longitude pendulum clock.

Now, however, the clock will take its place in the story of our planet and the Universe told in the Earth in Space gallery, demonstrating the innovative spirit and international collaboration so critical to Scotland's history.

We are grateful to the fine art auctioneer Dreweatts 1759 for their generous practical assistance with our purchase of this timepiece.

Acquired with support from