Key in a search term below to search our website.

Key in a search term below to search our website.

On 30 October 1942, at the height of the Second World War, two sailors gave their lives in the service of their country. Posthumously awarded the George Cross for their bravery, the crucial role they played in the war was to remain a closely guarded secret until the 1970s. How, then, did their story appear in a children’s comic in 1969?

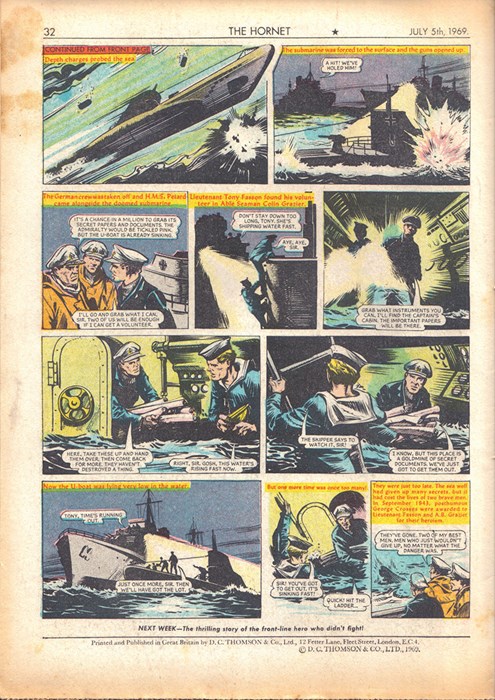

October 30, 1942, and Britain is at war. In Mediterranean waters off the Egyptian coast, four Royal Navy destroyers are attacking an enemy submarine, U-559. After a lengthy depth charge assault, the ships succeed in forcing the U-boat to the surface, the crew abandoning ship in desperation.

Naval officers knew the importance of salvaging papers and equipment from enemy craft; salvage that could contain vital secrets. Any secrets held by U-559 would soon be lost if immediate action wasn’t taken.

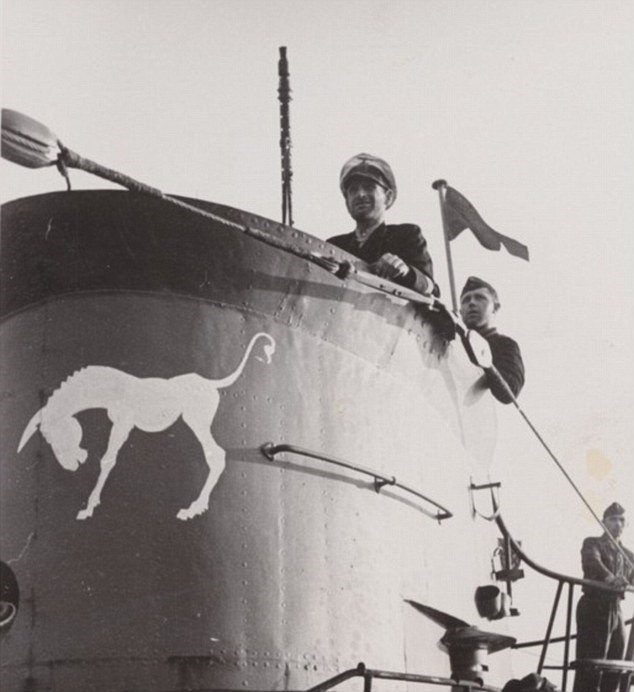

Above: The distinctive white donkey painted on the conning tower of the submarine made it easily identifiable as U-559.

First Lieutenant F.A.B. Tony Fasson, a Scotsman born and raised near Jedburgh in the Borders, was the first to volunteer. Together with Able Seaman Colin Grazier, from Tamworth in Staffordshire, he dived from his ship, HMS Petard, and swam towards the sinking submarine. Behind him, in one of the ship’s boats, came 16-year-old canteen assistant Tommy Brown, who had lied about his age when joining up at just 15.

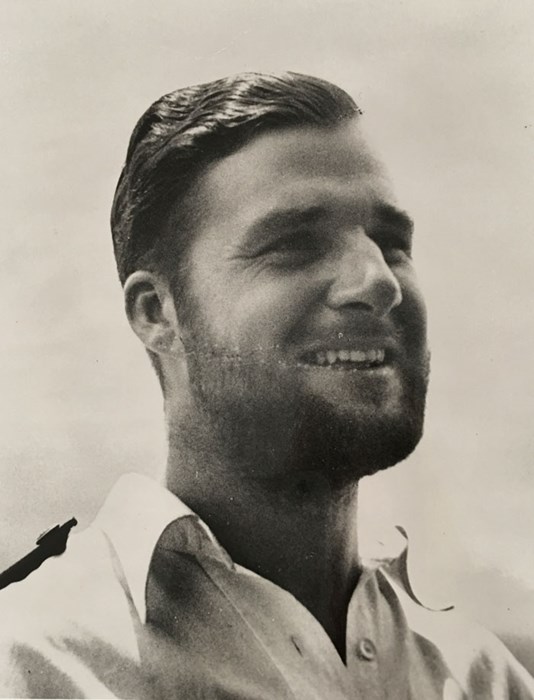

Above: First Lieutenant F.A.B. Tony Fasson.

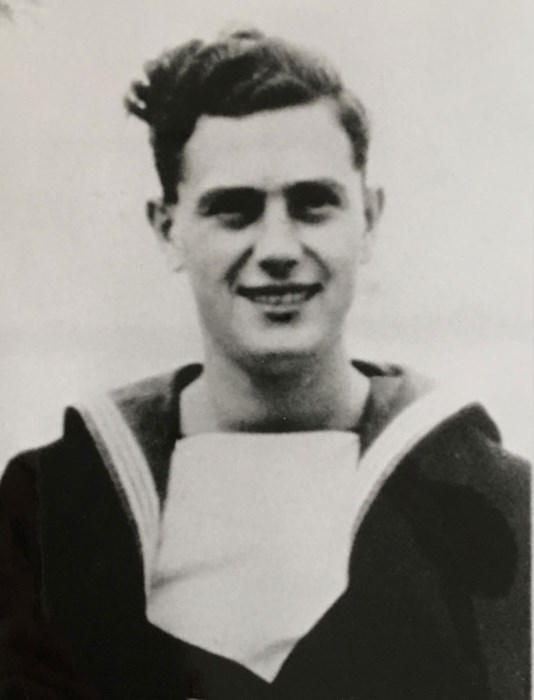

Above: Able Seaman Colin Grazier © The Royal Navy Trophy Fund.

The two men boarded the submarine, where they discovered some documents in the captain’s cabin. They handed these to Brown, who managed to keep them dry despite the rising waters – vital as they were printed in water soluble ink – then returned to try and detach some equipment from the control room.

As water continued to pour into the stricken vessel, Brown shouted a warning, but before Fasson and Grazier were able to escape, U-559 sank down into the depths, taking the two men with her. Fasson was 29 years old, and Grazier just 22.

Above: HMS Petard in 1943 © IWM (A 21715).

Yet the lives of these two brave men had not been lost in vain.

Back in Britain, scientists at the top secret codebreaking centre at Bletchley Park were struggling to crack new alterations to the Enigma code system used by the German military to communicate information. Cryptanalysts at Bletchley, including Alan Turing, had broken the now-famous code in 1940. But by 1942, the German Navy had upgraded their machines, plunging the codebreakers into darkness for ten months. With the Allies no longer able to track the locations of German U-boats, convoys carrying vital supplies across the Atlantic were left vulnerable to attack and destruction.

Above: Four-rotor Enigma machine made in 1944. You can find out more about this machine here.

The papers Fasson and Grazier had rescued, a Short Weather Cipher (Wetterkurzschlussel) and Short Signal Book (Kurzsignalsheft), were sent to Bletchley Park, arriving there on 24 November 1942. These books provided the vital clue required to crack the new codes. Almost immediately after this breakthrough, the Navy was able to reroute convoys to avoid waiting U-boats and plan their attacks.

Due to the intense secrecy that surrounded Bletchley, the actions of Fasson, Grazier and Brown could not be revealed for many years. Yet their contribution helped change the course of the Second World War, saving an estimated 1,250,000 tons of shipping in just two months and paving the way for D-Day in 1944 and the eventual victory of the Allies a year later.

“Few examples of courage by three individuals can ever have had so far-reaching consequences.- Ralph Erskine, Naval Historian

Fassion and Grazier were both awarded the George Cross, with an announcement published in the London Gazette on 14 September 1943:

“The King has been graciously pleased to approve the posthumous award of the George Cross to: — Lieutenant Anthony Blair Fasson, Royal Navy. Able Seaman Colin Grazier, P/SSX.25550 - for outstanding bravery and steadfast devotion to duty in the face of danger.

These medals are now on display in the National War Museum at Edinburgh Castle.

Above: George Cross medal awarded to First Lieutenant Tony Fasson.

Brown was awarded the George medal. He survived the war but tragically died trying to save his sister from a house fire in 1945 – a hero to the end.

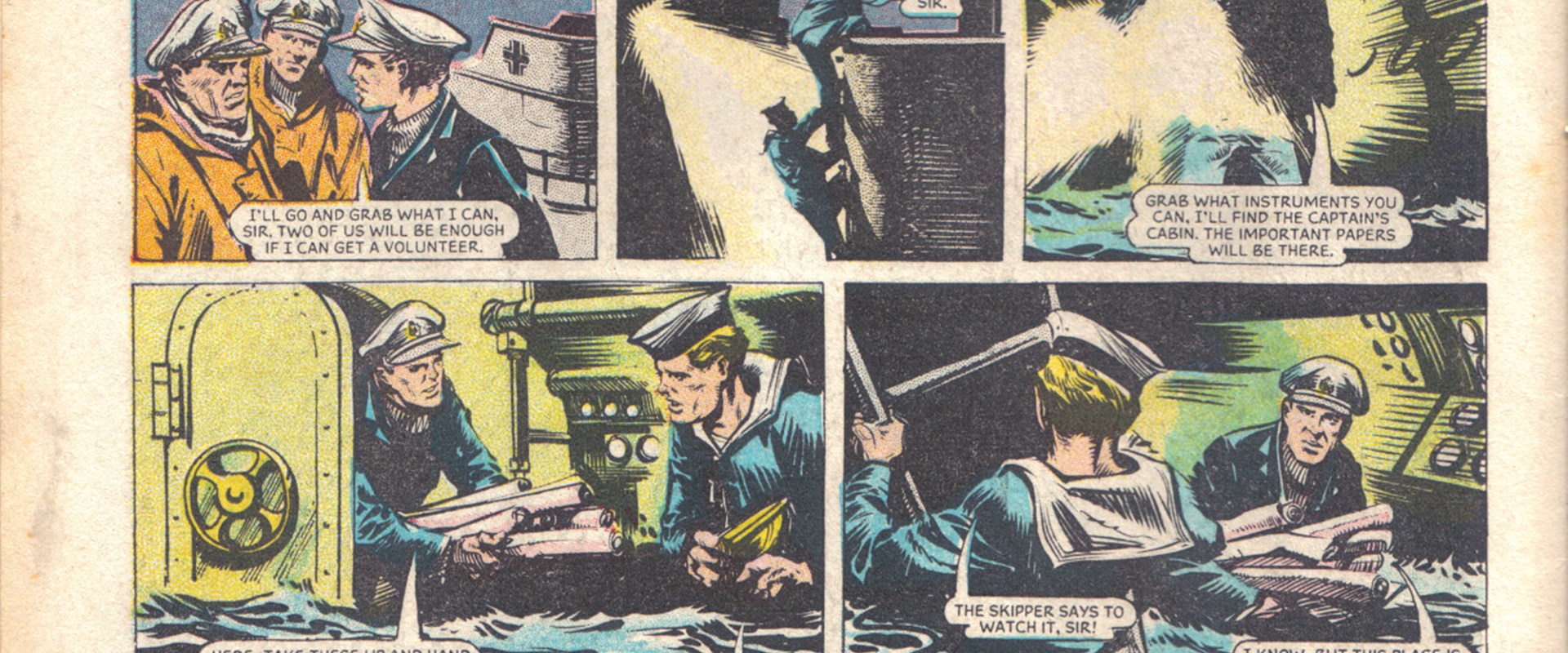

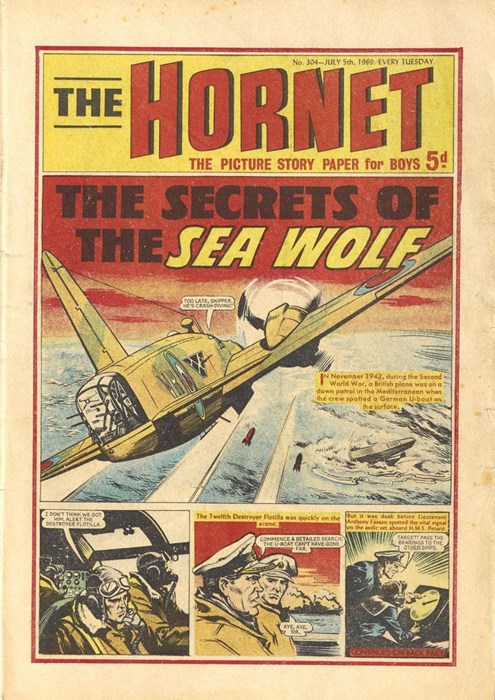

Protected by the Official Secrets Act, the clandestine work carried out at Bletchley Park – ‘Britain’s best kept secret’ – was not revealed until 1974, 29 years after the war ended. Yet in 1969, issue 304 of DC Thomson’s boys’ comic The Hornet told a tale of derring-do almost identical to Fasson and Grazier’s – even including their names. (Poor Brown’s role was omitted!) Clearly, someone had broken the Official Secrets Act to tell the story of the heroes of U-559. But who that was we may never know…

Above: 'The Secrets of the Sea Woof in The Hornet © DC Thomson & Co Ltd. You can see the comic next to the Enigma machine in the Communicate gallery at the National Museum of Scotland.