10 Roman objects found in the Scottish Borders

News Story

These objects found in the Scottish Borders, mainly from the Roman fort of Trimontium (modern Newstead), help paint a picture of the Romans in Scotland. Over 200 items, including these highlights, are on loan to the Trimontium Trust. Their award-winning museum in Melrose tells the story of the Roman Empire’s invasions of Scotland.

1. Iron Age copper-alloy armlet

This armlet shows the skills and connections of Iron Age societies in the Borders at the time of the Roman conquest. Making a large casting such as this took great expertise: it weighs 600g and is 11cm across.

The flowing decoration is typical of Celtic art in Northeast Scotland, and it was clearly imported from this area. A later owner has trimmed the edges to make it fit them better. It was found with another armlet (now lost) while digging a well at Stichill, north of Kelso, in 1747.

Copper alloy armlet found at Stichill, Roxburghshire, 100 - 200 A.D. Museum reference X.FA 17.

2. Leather shoes

These leather shoes survived so well because they were thrown into a well, and the waterlogging preserved them. The different sizes highlight the range of people living in and around the fort. These shoes are for a man, a woman and a child.

Just like today, shoes could be ornate fashion statements with cut-away patterns and stamped decoration. The adult shoes are stitched together from several different pieces of leather, with a hard-wearing sole consisting of multiple layers secured with iron hobnails. The child’s shoe is cut from a single piece of leather. These shoes were thrown away because they were worn out.

3. Brass arm guard

Roman soldiers were heavily armoured to protect themselves in battle. Infantry often wore a flexible arm guard (museum reference X.FRA 116.2) on their sword arm. The metal would stop the cut of a blow, with a padded lining to absorb the shock. Most arm guards were of iron, but this one is of brass, one of only three known from the whole Roman empire. This is the lower part, tapering towards the hand which was protected by the rectangular plate. Small holes in the corners once held rivets for leather straps; the larger holes at the ends were used to fasten the padded lining.

Lower part of a lamellar arm guard of bronze, from the Roman site at Newstead (Trimontium), Roxburghshire, 80 - 180.. Museum reference X.FRA 116.2.

4. Iron dolabrae (pick-axes)

The pick-axe, dolabra (museum reference X.FRA 225, 226, 227, 228, 229, 230, 231), was a fundamental part of a soldier’s kit. It was a multi-purpose construction tool, mounted on a wooden shaft and used for breaking ground, shaping timber, and levering things into place. Some of these examples have damaged edges from heavy use.

5. Iron scythe

This scythe (museum reference X.FRA 288) is a formidable tool, almost 80cm long, which was used to gather hay for ever-hungry cavalry horses. The blunt end once fastened to a long wooden shaft. Its remarkably good condition is because it was buried in waterlogged conditions, preventing the iron from rusting.

Iron scythe blade, from the Roman site at Newstead (Trimontium), Roxburghshire, late 1st century AD. Museum reference X.FRA 288.

6. Iron hanging lamp

In the long dark nights of a Caledonian winter, soldiers needed light. In the barracks, this came from burning wooden torches or tapers, or the light of a fire. For the officers, oil lamps lit up their quarters. This iron example (museum reference X.FRA 1108) is similar to a traditional Scottish crusie lamp. Its long spike allowed it to be stuck into a timber or hung from a hook at different angles.

Olive oil was poured into the figure-of-eight base, and a wick of rush or cord was hung over the edge and lit. The attention lavished on small decorative details, such as twisting the rod and rolling the ends of the hooks, shows that this was an expensive item.

Iron hanging lamp from the Roman site at Newstead (Trimontium), Roxburghshire. Museum reference X.FRA 1108.

7. Bronze cooking pot

The soldiers in one barrack room cooked communally. Vessels like this (museum reference X.FRA 1187), hammered to shape out of bronze sheet, were highly practical. They were much more durable than pottery, making them suitable for campaign use as well as back at base. Pairs of holes in the rim once held fittings for an iron carrying handle.

Bronze camp kettle from the Roman site at Newstead (Trimontium), Roxburghshire. Museum reference X.FRA 1187.

8. Pair of imported quernstones

Quernstones were used by soldiers to grind flour for baking bread. Grain was poured into the hole in the top. The iron plate held a spindle which stabilised the two stones and allowed the fineness of the flour to be adjusted. A wooden handle in the iron socket on the edge was used to turn the upper stone. This crushed the grain and flour fell out of the edge between the two stones.

The best querns were made from imported lava from Mayen, near Koblenz in western Germany. The natural bubbles in its structure meant it didn’t wear out, and that there were always fresh sharp edges exposed. Finished querns were shipped up the Rhine and across the North Sea.

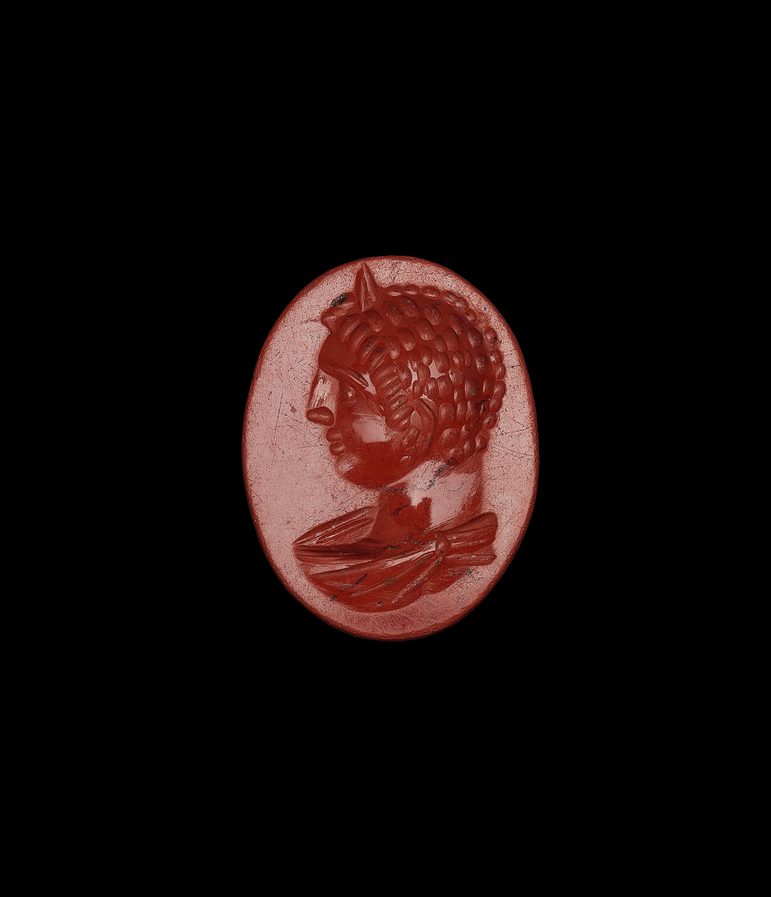

9. Gemstone showing the emperor Caracalla

The fields around Newstead have produced a rich crop of Roman gemstones. This remarkable example (museum reference X.2000.4) was discovered by local amateur archaeologist Walter Elliot when he was walking over the ploughed fort site in 1998. It brings alive a key moment in Scotland’s history when massive Roman armies marched north in AD 209 and 210 to quell unruly tribes. This huge army was led by the emperor Septimius Severus and his son and co-emperor Caracalla, whose face is carved into this gem.

The gem of red jasper was once set into a ring, probably of gold. It was given as a personal gift from the emperor to one of his close supporters who was travelling with him. The recipient must have been rather worried about the emperor’s reaction when he discovered the gem had popped out of the ring!

Intaglio of Caracalla of red jasper and having a draped bust and facing left, from Newstead (Trimontium), Roxburghshire. Museum reference X.2000.4.

10. Iron ring with a gem showing Maenad

Carved gemstones were both beautiful and functional. This example (museum reference X.2000.17.3) is the only one from Trimontium which still preserves its iron finger ring. Gem-set rings were practical jewellery: the design on the gem acted as the owner’s mark when they impressed it in wax seals.

The designs often featured deities or mythical figures. This one shows a Maenad, a female follower of the wine-god, Bacchus. She is playing an aulos, a double-pipe, and dancing ecstatically, her dress flowing as she spins. For the wearer, this probably evoked the good life they dreamed of.

Nicolo intaglio depicting a Maenad dancing and playing the double pipes (‘auloi’, set on an iron ring. Part of the Cruickshank collection of finds from Newstead (Trimontium), Roxburghshire. Museum reference X.2000.17.3.