10 stories of disability history in the collections

News Story

Disability History Month begins in November each year. But all year round we care for and interpret objects connected to the lives and experiences of D/deaf, disabled and neurodivergent people, past and present. This list highlights objects in our disability history collection that relate to livelihood and employment.

1. A chanter from a piping dynasty

This chanter belonged to Iain Dall MacKay, who was one of the most important pipers and composers of the 17th and 18th centuries. He was blind from childhood and studied with the MacCrimmon family of pipers in the Isle of Skye . In 1805, the chanter was taken to Nova Scotia, Canada, by Iain Dall’s grandson John Roy and preserved by his descendants through eight generations before being donated to the museum in 2010.

It is one of the earliest examples of a chanter in our collections, and its link to Iain Dall makes it an incredibly significant survival. Extensive research has been done on this chanter by Julian Goodacre and Barnaby Brown to produce a replica of it to find out how it sounded. This research demonstrates that his bagpipes were similar in volume to modern examples but produced a lower, warmer tone close to a modern B flat.

Chanter of Iain Dall MacKay (1656-1754). Museum reference K.2010.92

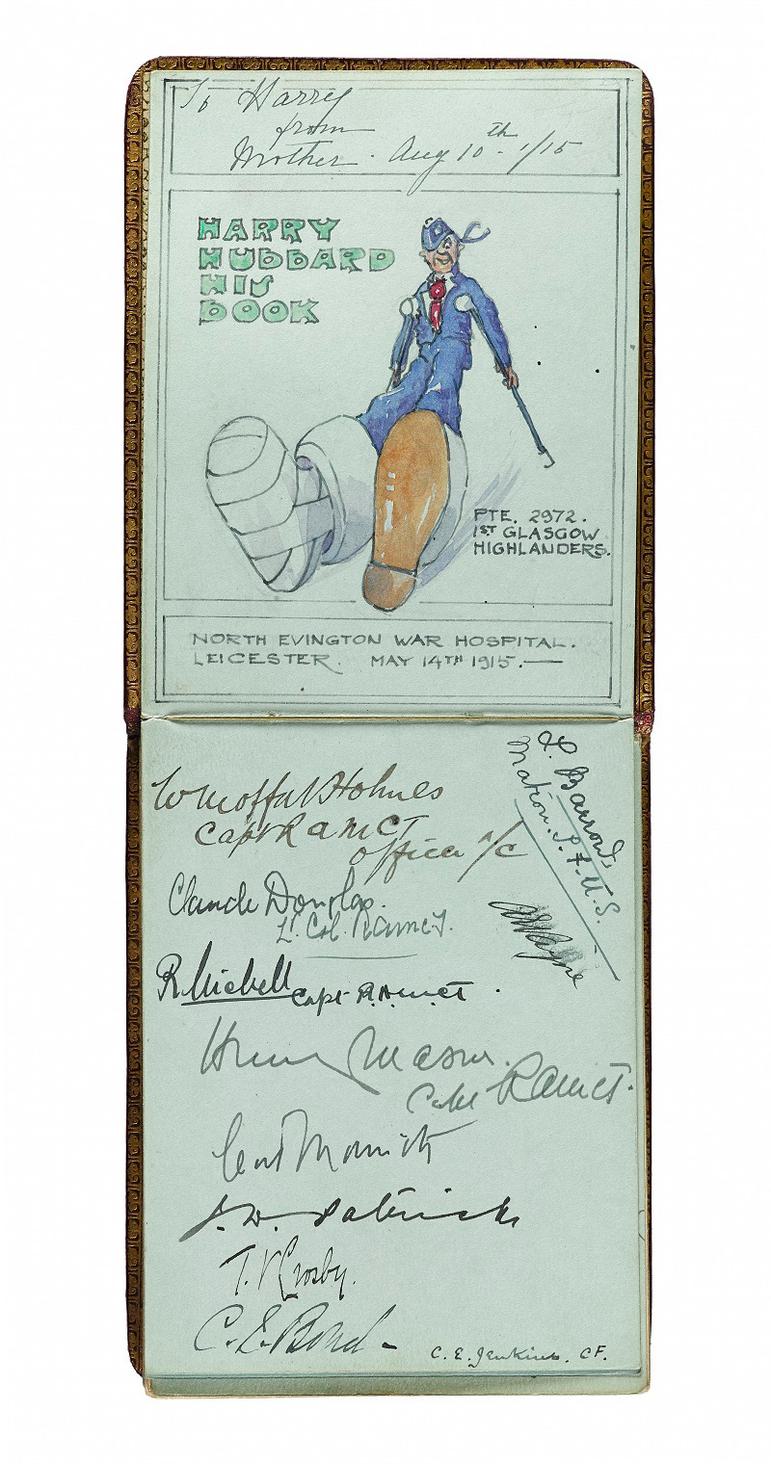

2. An autograph book of a First World War soldier

This autograph book was compiled by Private Harry Hubbard when he was in North Evington War Hospital, Leicester, in 1915. Many soldiers who were injured, lost limbs or were diagnosed as having ‘shell shock’ (a type of post-traumatic stress disorder) during the First World War created art, wrote poetry or did crafts as part of their rehabilitation.

We hold several autograph books and craft items produced by recovering soldiers in our collections. These books contain a mixture of humorous and sentimental pictures and messages. Art and crafts in hospitals could alleviate boredom, improve dexterity after injuries, or have a therapeutic benefit. Alongside art and crafts, many permanently disabled veterans were given access to vocational workshops, such as those at Erskine Hospital. This meant that those veterans who were able to work could gain new skills so they could get jobs once they left hospital or could be employed in sheltered workshops, such as the ones at Erskine.

Autograph book of Private Harry Hubbard, Highland Light Infantry (Glasgow Highlanders). Museum reference M.1994.1.4

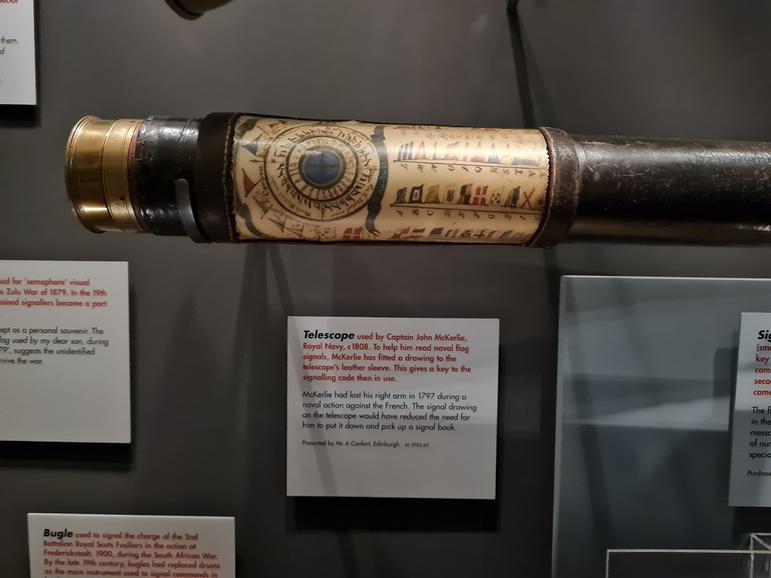

3. An adapted telescope

Rear Admiral John McKerlie joined the Royal Navy in 1794 and lost his arm three years later whilst serving aboard the HMS Indefatigable. However, like many other people in the military who had lost limbs, he continued to serve in the navy and McKerlie later fought at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805.

This telescope shows how McKerlie adapted objects to make them easier to use with one arm. It has a leather sleeve with naval flag signals placed into a pocket on the side. This meant he did not need to put it down to look in his signal book and could just turn the telescope sideways to check the symbols. National Museums Scotland also holds McKerlie’s naval dirk, which was a weapon that he favoured for close-fighting because it was easier to wield with one arm.

Telescope of Rear Admiral John McKerlie (1774-1848). Museum reference M.1955.65

4. A racing wheelchair

Scottish Paralympic athlete Karen Lewis-Archer used this wheelchair during her sporting career. It was made by Top End in Florida, USA. Lewis-Archer was a well-known and respected wheelchair racer, competing in the 2000 and 2004 Paralympic Games as well as other international championships. She started her sports career as a swimmer but switched to wheelchair racing after joining the track relay team at the last minute during the World Youth Games in Miami in 1989, helping them win a gold medal.

This lightweight racing wheelchair was used by Lewis-Archer to win gold medals in World and European championships. After Lewis-Archer retired from competing, she continued to be a significant supporter of disability sports as the first National Development Officer for Scottish Disability Sport. Her work promoted inclusion and access to sports in Scotland for people with a range of physical, intellectual and learning impairments.

Racing wheelchair used by athlete Karen Lewis-Archer (1974-2016). Museum reference SH.2006.8

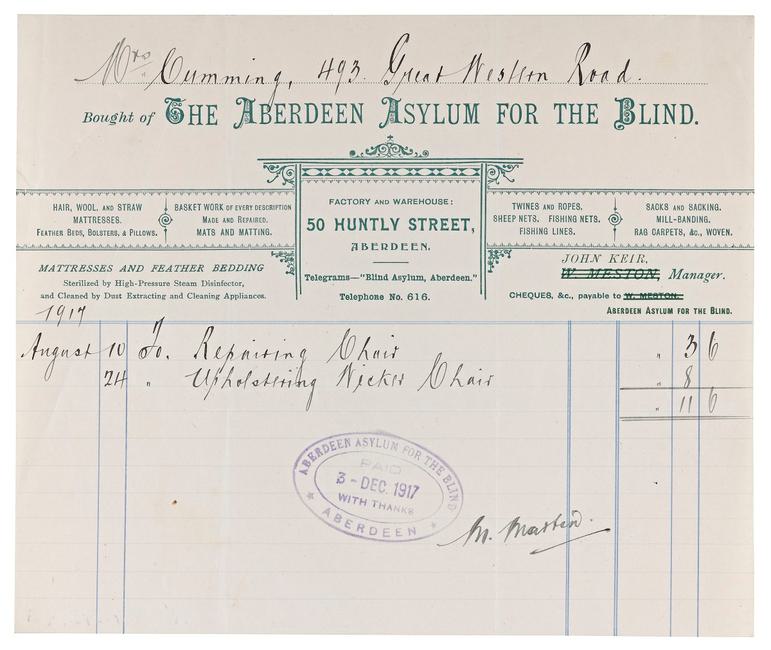

5. An invoice for The Aberdeen Asylum For The Blind

This invoice shows the range of objects made by people working in impairment-specific workshops. During the 19th century, workplaces called ‘asylums’ were established to provide training and employment for people who were blind or D/deaf. Many of these places had connections with schools for blind or D/deaf children that had been established in the 18th and 19th centuries.

These asylums often did not provide good pay and were run as very strict environments. However, blind piper and teacher Archie McNeill recounted how in 1918 he was involved in strikes with the National League of the Blind, the Co-operative Society, the miners’ and other union organisations. This strike action resulted in better pay for workers at the Glasgow Blind Asylum where he was employed.

Headed invoice from The Aberdeen Asylum For The Blind, 50 Huntly Street, Aberdeen, 1917.Museum reference W.MS.1997.173.43

6. Dedicated schools for D/deaf, blind and disabled children

Since the 18th century, there have been a range of schools in Scotland providing education and vocational training for D/deaf, blind and disabled children. One such school established in 1850 is Donaldson's School. Originally the school used a system of integrated co-education, with half the pupils D/deaf and half hearing, then the school became exclusively for D/deaf children in 1938.

This photograph shows senior pupils at Donaldson’s School in 1959 learning woodworking and carpentry. Other skills that were taught at the school included gardening, printing, tailoring and shoemaking for boys, and cookery and domestic work for girls. Donaldson’s has always taught using British Sign Language (BSL), leading to D/deaf and hearing pupils becoming teachers, interpreters and social workers. Teaching BSL to hearing pupils and parents at Donaldson’s throughout its history has connected D/deaf and hearing communities and helped promote greater understanding of D/deaf issues.

Two senior pupils at Donaldson's School in Edinburgh, 1959.

7. A ceramic poppy crafted by a disabled artist

Paul Cummins MBE is an artist with colour associated dyslexia and an impairment in his hand, which he acquired when installing ‘Blood Swept Lands and Seas of Red’ at the Tower of London. Cummins is most well-known for his large-scale installations of ceramic flowers, producing work for the London 2012 Cultural Olympiad, Chatsworth House, Derby Royal Hospital, RHS Chelsea Flower Show and Blenheim Palace.

This ceramic poppy is from the installation he designed for the First World War commemorations in 2014 in collaboration with theatre designer Tom Piper MBE. The installation included 888,246 ceramic poppies, each one representing a British or colonial serviceman who died in the war, creating a sea of red around the Tower of London. Paul commented that "I thought the country would take the project to their hearts but not the whole world. It was quite amazing".

Ceramic poppy from 'Blood Swept Lands and Seas of Red' at the Tower of London, 2014. Museum reference M.2015.3.1

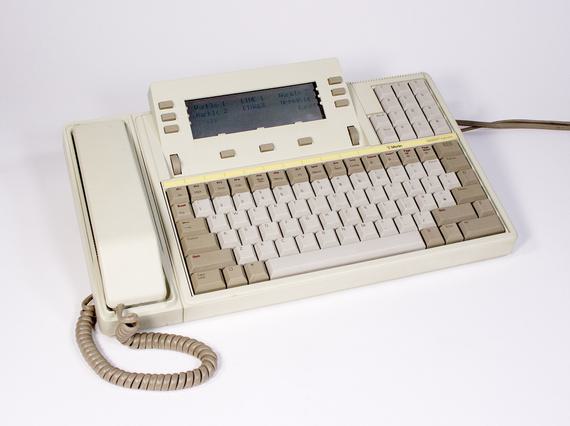

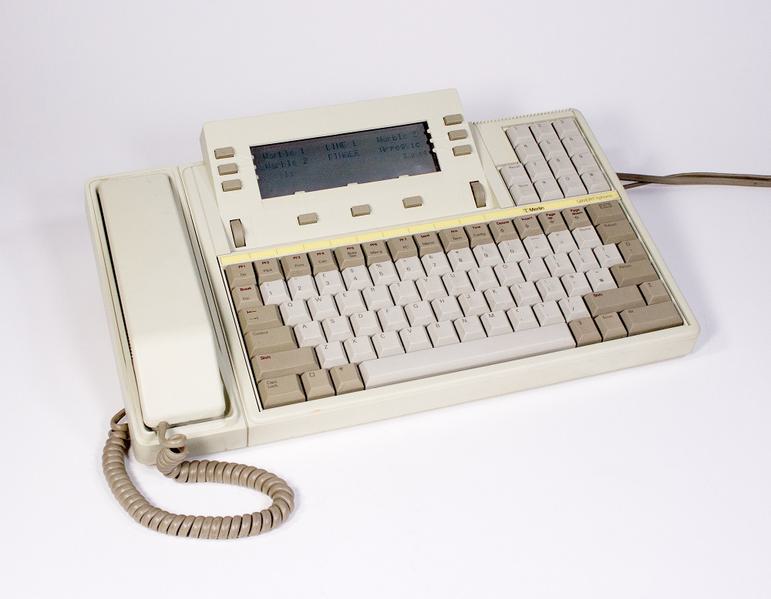

8. An accessible telephone

This work telephone was supplied by BT to the Assistant Curator of Earth Sciences at the New Walk Museum, Leicestershire Museums, c1989 to support him at work. It was made by Merlin and has a QWERTY keyboard, rectangular screen, number keypad, handset and a printer that could be attached to allow messages to be read on paper. Domestic telephones like this one were also supplied to D/deaf people through the Royal National Institute for Deaf People.

The phone was designed with ease of use in mind, in the introduction of the user manual it states "DO NOT BE AFRAID TO TRY THINGS OUT. YOU CANNOT HARM THE QWERTY phone by simply pressing a few wrong keys." The donor of this phone remembers how in the mid-1990s “the Qwertyphones became redundant, and a few years later officially obsolete. But in their day they were a lovely bit of kit”.

Telephone supplied by BT for D/deaf customers made by Merlin, 1986. Museum reference T.2003.291.1

9. A carte-de-viste of conjoined twins Eng and Chang Bunker

Eng and Chang Bunker were born in Siam (now Thailand). This is where the phrase ‘Siamese Twins’ originates. It's a description applied to conjoined twins that remains to the present day. In 1829, they met Scottish merchant Robert Hunter who offered them the chance to emigrate to the United States and work as circus performers.

Eng and Chang toured extensively across the USA, Europe and the UK throughout the 1830s. Their substantial earnings funded the purchase of land in North Carolina and enslaved people to work the plantation and maintain their lifestyle. They married sisters Adelaide and Sarah "Sallie" Yates and built homes close to one another. Eng had 11 children while Chang had 10. After the American Civil War and the abolition of slavery, their finances took a downturn. Returning to the performance circuit with PT Barnum they failed to gain the attention they had previously received.

Carte-de-visite of Eng and Chang (1811-74). Museum reference T.2023.44.4.247

10. A wedding photograph of Lavinia Warren and Charles Stratton

This carte-de-visite shows Lavinia Warren and Charles Stratton in their wedding outfits in 1863. Both were successful American entertainers who had dwarfism. Warren was a gifted singer and dancer and Stratton was a skilled actor and comedian, known as General Tom Thumb. The couple amassed considerable wealth that allowed them to purchase a steam yacht and properties in New York and Connecticut.

PT Barnum presented the couple as childlike to the public which frustrated Warren, “It seemed impossible, to make people understand at first that I was not a child; that, being a woman, I had the womanly instinct of shrinking from a form of familiarity which in the case of a child of my size would have been as natural as it was permissible”. After Stratton died, Warren created a small opera company with two Italian performers with dwarfism. They were called “Count” Primo Magri and his brother “Baron” Giuseppe.

Carte-de-visite of Lavinia Warren (1841-1919) and Charles Stratton (1838-83). Museum reference T.2023.44.4.471