100 years of the Little Black Dress

News Story

The ‘Little Black Dress’, or ‘LBD’, first captured the fashionable imagination in the 1920s. It was radically modern and masculine-inspired, and was free from the earlier constraints on women’s dress.

In 2023 National Museums Scotland presented an exhibition Beyond the Little Black Dress. It brought together 65 looks from museums and designers around the world. Over one third of these looks come from the museum’s permanent collection. This represented a chance both to showcase some of our collections held in storage and to acquire new pieces for the national collection.

The colour black is open to myriad interpretations. It is at once expressive of piety and perversion, respect and rebellion. But how we interpret the colour can also be influenced by our cultural background, faith, gender, political affiliation, or economic situation. In this way, the LBD is a blank canvas on which to project identity and cultural meaning. Examine the evolution and reinvention of the LBD in popular culture in the 20th and 21st centuries, through garments from our collection.

Well mannered black

The LBD has long been a shorthand for good taste. In 1954, Christian Dior’s The Little Dictionary of Fashion declared it appropriate to wear black at any time, any age, and for almost any occasion. At once the cloak of mourning and the uniform of the chic socialite, it is also a symbol of sexual sophistication. Paradoxically, the LBD can be modest and polished, bold and alluring. It treads a delicate line between respectability and rebelliousness.

Fashions of the 1920s shunned the constraints society imposed on women. New designs reinforced post-war ideas about liberated womanhood. In 1926, Coco Chanel introduced a famously simple, black day dress. American Vogue hailed it as ‘the frock that all the world will wear’. It was the epitome of modern womenswear – loose, comfortable and relatively unadorned. Until, in 1947, Dior’s ‘New Look’ revived a voluptuous femininity in women’s dress. Based on tight corsetry, voluminous skirts, and pointed brassieres, it straddled the demure and the erotic.

In the mid-20th century, the LBD had become synonymous with the ritual of the cocktail hour. The cocktail hour originated with prohibition in the 1920s. It quickly become a daily ritual for which society women needed a new wardrobe. By the 1950s, Christian Dior defined the perfect cocktail dress as elaborate ‘afternoon dresses’ in black taffeta, satin, chiffon, and wool. In 2018, National Museums Scotland acquired the Ligne Longue cocktail dress by Christian Dior. It is made of black silk faille and featured in Dior's 1951 Autumn/ Winter collection. It was one of the first pieces we acquired for the museum’s exhibition on the LBD.

Designing in black

Former Vogue editor Diana Vreeland, once said that black is the hardest colour in the world to get right. Its starkness focuses the eye on the core elements of design – texture, tone, and silhouette. By turns opaque or transparent, matte or shiny, the play of light across the surface of the textile can reveal or conceal design details. While the absence of colour accentuates the architecture of the garment. With nowhere to hide, the designer’s technical skill is paramount.

Designers like Cristóbal Balenciaga, Yves Saint Laurent, and Jean Muir are united in their reverence for the craft of dressmaking. All are especially renowned for their mastery of the little black dress. Their understanding of the properties of specific fabrics allowed them to eliminate superfluous lining and underpinnings. They constructed garments so sophisticated that they have transcended fashion’s changing trends.

Jean Muir is famed for her timeless, sensual designs. Her signature fabrics were matte jersey, wool crepe, buttery soft leathers and suede. This 1970s shirt dress of black suede is part of Miss Muir’s extensive archive held by the National Museum.

Other examples of designers turning to the colour black include this embellished silk robe de style designed by Jeanne Lanvin in 1926. In 2018, the museum also acquired the Cygne Noir (Black Swan) evening dress. Made in black tulle and lace, it was created by Yves Saint Laurent for the House of Dior in the late 1950s.

Yves Saint Laurent was an exceptional colourist. But his LBDs and Le Smoking tuxedos formed the backbone to his collections. Following Dior’s death in 1957, Saint Laurent was appointed art director for the famous house. The ‘Black Swan’ dress was inspired by the character of Odile in Swan Lake. In the 1940s she first became known as the black swan and inspired many couture creations.

Image gallery

Dress of black suede, by Jean Muir Ltd, c. 1970s (K.2005.649.1392.1-2)

Subversive black

Black has long held symbolic associations with rebellion and transgressive behaviours. It is the colour of nihilism, revolution, and solidarity. Black has been adopted by various 20th century subcultural movements, from punk and goth to streetwear.

The colour has also always been imbued with a seductive power. This is partly down to its cultural associations with sexual subcultures, and the erotic thrill of the socially ‘taboo’. In the 1980s, fetish signifiers were readily assimilated into mainstream fashion. This was seen as a subtext to sharp-suited power dressing. Bondage-inspired details and primarily black, ‘second-skin’ fabrics such as leather and rubber, flaunted sexuality as empowerment. Yet, they have also been critiqued as degrading and misogynistic.

Contemporary debates around sex-positive clothing are about not only subversive design, but also disrupting society’s restrictive beauty ideals. Irish designer Sinéad O’Dwyer’s debut at London fashion week was a celebration of female agency. It reinforced body positivity in an industry that has long promoted exclusive body ideals. O’Dwyer uniquely works in a sample size 18-22. Her sex-positive Spring/Summer 2023 collection pioritised comfort and subversive design equally. The show championed all bodies as equally desiring and desirable.

O’Dwyer worked with casting director Emma Matell. They wanted to challenge the body dysmorphia inherent to contemporary fashion. Together they street cast models whose sizes ranged from 8 to 26. Two of the models, Naadirah Qazi and disability activity Emily Barke, were wheelchair users. The garments evoked a fetishist aesthetic with ‘shibari’ or Japanese rope bondage-inspired elements. The accessories contain hidden symbols like references to the sexual metaphor of the cello.

Intrigued by O’Dwyer’s design practice, the National Museum acquired an ensemble from her Spring/Summer 2023 collection, custom made in a size 20. O’Dwyer’s approach starts with the model rather than the garment. She utilises a method she developed while studying at the Royal College of Art. There, she presented silicone body casts as wearable art.

From a design perspective, O’Dwyer’s mission is more difficult. She works from numerous block patterns at once and uses a range of around seven fit models. One standard fit model is the industry standard.

It represents a lengthy process of data-gathering. But O’Dwyer’s commitment is such that she chooses to reduce the number of items she is making each season. This allows her to focus instead on achieving a wide range of sizes per style. O'Dwyer references her own experience with body dysmorphia. She is acutely aware of the impact it has on mental health when luxury fashion excludes the majority. As such she is focused on developing techniques to design flexibly for differently sized bodies. She aims to create space within the pattern for curves rather than attempting to erase them.

Sexual politics

Fashion’s fascination with fetishwear illustrates how trends have fluctuated according to the sexual politics of an era. Especially considering that the rising hemlines of the 1920s incited scandal enough.

From the early 19th century, women were gaining greater independence. The suffrage movement was a key factor, and during the First World War more women entered the workforce.

This greater sense of freedom was reflected in styles of dress. The 1920s ‘flapper girl’ fashion was marked by shorter hemlines and androgynous silhouette. This was known as the ‘la garçonne’ (boyish) look . These styles empowered women to rebel against feminine norms. They also aroused controversy, partly due to social anxieties around changing gender roles.

Spiritual black

The implied sensuality inherent in the colour black is in part due to its association with sin. This connection is underscored by the teachings of the early Christian Church. Historically associated with demonic cults and witchcraft, black has morphed into a trope of evil.

Yet in ancient Egypt and other parts of Africa and Asia, black had both positive and negative associations. It was simultaneously symbolic of life and death. Black was linked to the fertile aspect of the earth, the passage to the afterlife, and the promise of rebirth.

A variety of belief systems have powerfully influenced the fashion for black. Contemporary fashion designers in the West often borrow creatively, and provocatively, from the disparate practices of Roman Catholic Christianity, occultism, and Paganism, with designs that bridge the sacred and the secular.

Black’s inherent monastic virtue is illustrated by the Catholic priest’s cassock and the nun’s habit. This connection has held a particular allure for designers. London label Cimone’s Autumn/Winter 2017 collection featured several looks with religious references. These were not necessarily tied to any one faith but were inspired by the notion of the undead, or the question of life and spirit continuing.

Black futures

The binary of black as evil and white as pure, is partially constructed in Western consciousness by the influence of Christianity. The 'Beyond the Little Black Dress' exhibition explored black as a colour, culture, construct, and as a global diasporic community.

The exhibition co-curator Sequoia Barnes worked with us to introduce a theme to the exhibition titled ‘Black Futures’. This section reconsidered ways of seeing and connecting to clothing through the lens of black and Blackness. Her selection explored the monochromatic, Afrofuturistic fashions created by seven leading Black British, or UK-based, fashion designers.

Afrofuturism has always been fluid in definition and style. It can be characterised as the creative use of technology and tropes of science-fiction to explore Black diasporic cultures, experiences, and concerns. Combined with symbols from the Black diaspora, the works created decolonise time and imagine liberatory futures. Afrofuturism also deconstructs meaning. In fashion, this encourages us to explore what a dress could be or what ‘dress’ can mean. We can consider racial, gendered and other expectations when it comes to ‘dressing’ up.

Techwear meets Afrofuturism

The designs of menswear brand A-COLD-WALL* are the epitome of when techwear meets Afrofuturism. British artist, designer, and multidisciplinary creative director, Samuel Ross, founded A-COLD-WALL* in 2014 . Before establishing his own label, he had worked as Virgil Abloh’s design assistant. Through his label, Ross explores societal issues, disparities, and realities faced by people living in inner-city London. He creates an aesthetic informed by his studies in graphic design, the British class systems, and Brutalism.

An ensemble by A-COLD-WALL* was generously donated to National Museums Scotland by the designer. The styling of the ensemble blurs human and post-human with its distorted angles and chrome body paint. It is an overt example of Afrofuturism’s appropriation of science-fiction tropes and cyborg aesthetics.

A new black

Fashion is one of the most energy-consuming, polluting, and wasteful of modern industries, exacerbated by cycles of endless consumption. In response, contemporary designers are seeking more sustainable solutions. These range from cutting-edge technologies to nature-led approaches.

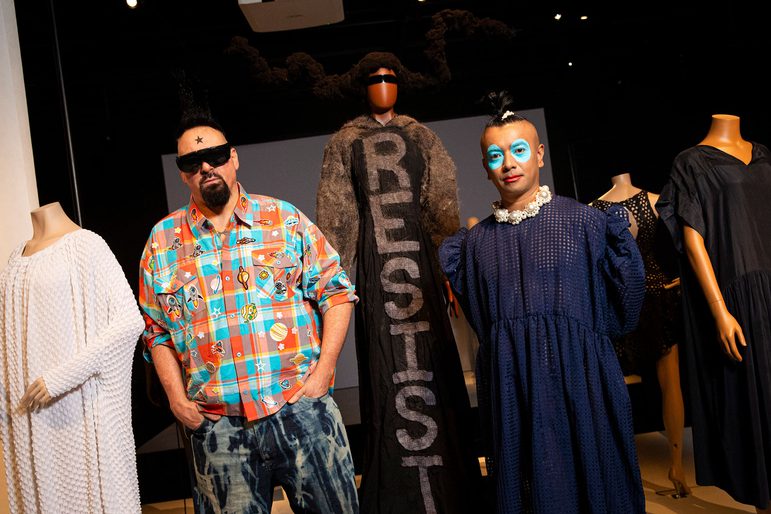

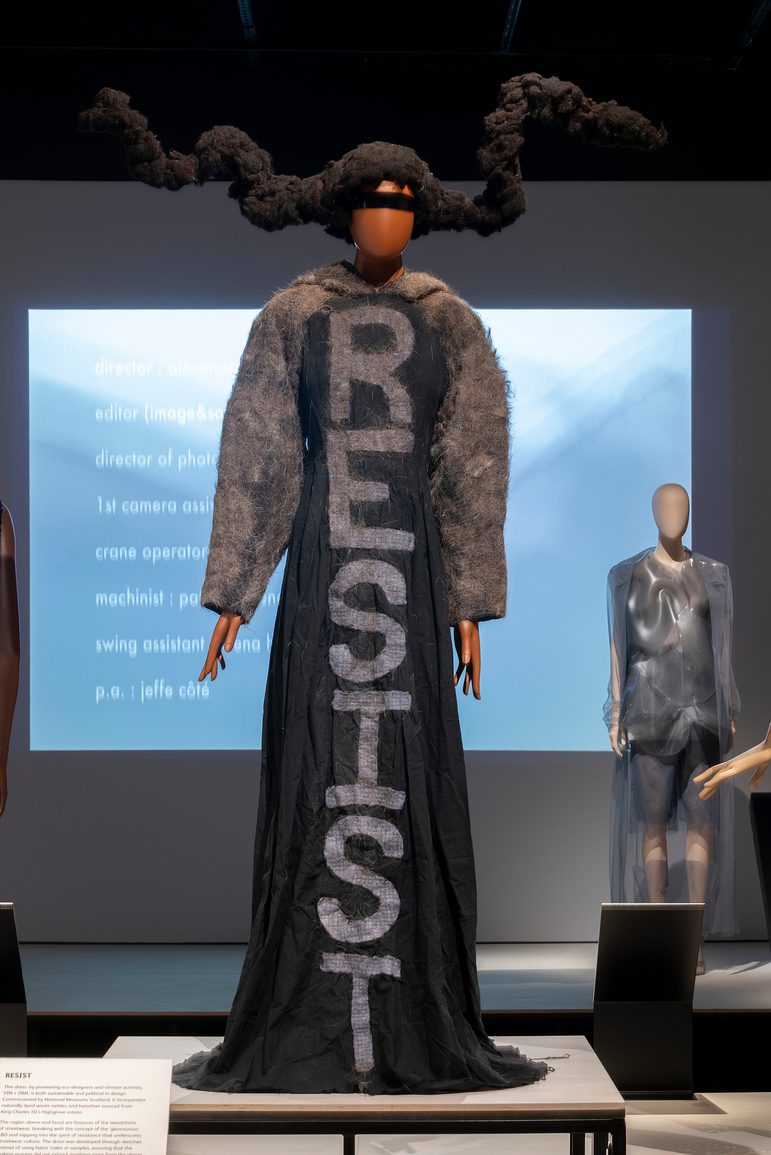

Pioneering eco-designers and climate activists, VIN + OMI, launched their brand in 2004. They use fashion to challenge both industry and consumer perceptions about sustainable ways of living. They show outside of London Fashion Week, staging their own catwalk a day before the official schedule starts. This is a rejection of the traditional fashion system that’s driven by commerciality.

The VIN + OMI manifesto is about continuing to seek unique solutions to a problem. They pioneer new processes and programmes, and track their carbon footprint. The energy used is tracked, even down to the calories expended in the making of a garment.

While they have dressed countless celebrities, they are also known for their social impact and environmental work. This includes global waste plastic clean up schemes. These initiatives work with local communities to turn the plastic into products and strive for a cleaner environment.

At VIN + OMI’s studio HQ in Norfolk, they grow a range of crops and plants for textile development and research.Since 2004, they have developed 32 unique to market textiles based on sustainable, eco-processes. These include rPET and hybrid textiles made via their ocean and river waste plastic collection schemes. They’ve also sourced sustainable, organic, and ethical latex from their own plantation in Malaysia. VIN + OMI also have a strong focus on textiles and products made from UK waste plant source. This includes pioneering ‘leathers’ made from chestnut, mushroom, and seaweed. Their ground-breaking nettle textile was made from waste nettles from King Charles III’s Highgrove estate.

National Museums Scotland commissioned VIN + OMI to create a unique piece in response to the exhibition on the LBD. The resulting ‘RESIST’ dress featured as the finale to VIN + OMI’s Autumn/Winter 2020 catwalk.

The dress incorporates naturally dyed waste nettle fibre and horsehair sourced from Highgrove. The design includes a raglan sleeve and hood, which are features of the sweatshirts of streetwear. This breaks with the concept of the silky, ‘glamourous’ LBD and taps into the spirit of resistance that underscores streetwear culture.

Refashioning black

The fashionable black dress was a practical and versatile option for women over 100 years ago. During the Second World War it doubled up as mourning wear and a formal afternoon dress. Today the LBD is still considered a wardrobe essential and a keystone of slow fashion. In all its derivations it has absorbed countless trends from across the fashion spectrum. The LBD captures and reveals changing definitions of gender, sexuality, ethnicity, status, and class.