A brief history of James VI and I

News Story

James VI and I was a hugely significant Stewart king. But he has been overshadowed by his notorious relations. His predecessor in Scotland was his mother, Mary, Queen of Scots. In England, his cousin, Elizabeth I, and finally his successor in both kingdoms, Charles I.

Who was James VI and I?

Born in 1566, James VI and I was the product of Mary’s ill-fated marriage to Henry, Lord Darnley. Darnley’s assassination in early 1567, and Mary’s subsequent over-hasty marriage to one of its perpetrators, Lord Bothwell, triggered events that led to Mary’s downfall.

James VI became king of Scotland in 1567 when Mary was forced to abdicate. On the death of Elizabeth in 1603, he became James I of England. He is thus known as James VI and I.

In 1590 he married Anna, the sister of the Danish king, Christian IV. They had numerous children, three of whom survived infancy. Henry, who died after a short illness in 1612, Charles who was to succeed James, and Elizabeth, who married Frederick, elector of Palatine, and the swiftly deposed King of Bohemia. Romantically she has become known as the Winter Queen.

Unlike his mother or his son Charles, James died of natural causes in his own bed in 1625.

Engraving of Mary Queen of Scotland with her son (later James VI and I), after a painting by F. Zucherri, published 1779. Museum reference M.1934.447.

A notable monarch

James was one of the most long-standing monarchs of Scotland, king for 58 years from the age of one. Of the Scottish monarchs before the Anglo-Scottish union of 1707, only William the Lion (1165–1214) comes close in longevity.

But he is notable not just for the length of his reign, but for the amount that he managed to achieve within it.

Of these achievements, perhaps the most significant of all was his careful management of his peaceful succession to the English throne in 1603. In doing so, he brought the ‘auld enemies’, the kingdoms of Scotland and England, together under the kingship of one monarch. This dynastic union became known as the ‘Union of the Crowns’, which included that of Ireland too. In 1604, James proclaimed himself King of Great Britain. So James’s reign produced the first Anglo-Scottish union (though this was not full political union). This helped to form the background to the formal union of 1707.

James and Mary, Queen of Scots: a troubled relationship

In 1567, at the age of one, James was placed in Stirling Castle for his care and safety. Following a visit to see him, Mary was ‘abducted’ by James Hepburn, Lord Bothwell (whether or not she was a willing participant is unknown) and forced into marriage to him. This visit proved to be the last time James ever saw his mother.

Over the next twenty years they had a difficult relationship. It was hampered by the physical distance between them, the problems of communication by letter or word of mouth, and dependent on who had custody of the young king. Most importantly, there were tensions over Mary’s attempts to regain her Scottish throne during her English captivity. Mary’s return would have compromised James’s own kingship. Famously, James did little other than protest to Elizabeth over Mary’s execution in 1587.

The Penicuik jewels. This locket is said to show Mary, Queen of Scots and her son James on the reverse. Museum reference H.NA 422.

James ordered a splendid tomb to be made for Mary in Westminster Abbey when he became king of England. Mary’s marble tomb with its elaborate canopy outshines the one he created for his predecessor on the English throne, Elizabeth I.

In death you could say that Mary triumphed over the queen that had signed her death warrant. In memorialising Mary in such a way, James perhaps assuaged any guilt he may have felt. Given her claim to the English throne (as a great-granddaughter of Henry VII), Mary would have thought it fitting to be laid to rest alongside other English monarchs.

Plaster cast of the tomb of Mary, Queen of Scots. Museum reference

IL.2001.192.

The boy king

As an infant, James had councillors ruling in his name, but he took up his personal reign in his mid-teens, in the early 1580s. His childhood was spent at Stirling castle in the care of Annabella, Countess of Mar, whose son became a lifelong friend of the king. He was tutored by the stern Presbyterian and humanist George Buchanan.

James was a clever boy, very well educated, who learnt the art of argument early. In 1579, aged 12, he made a formal entry as king into Edinburgh. But in the years following he suffered from political and religious factionalism at court. In 1582 he was abducted in the Ruthven Raid by several nobles, including the earl of Gowrie, who wanted to ensure a Presbyterian-inclined government of Scotland.

By 1585, however, James was old enough to begin to impose his own will on the feuding factions.

James VI as a boy, by an unknown artist.

God's lieutenant on earth: James as king

James had strong views on the rights of kings. His tutor Buchanan’s book De Jure Regni had called for a contractual monarchy in which kings can be held to account for their actions. This was an attempt to legitimise the overthrow of James’s mother Mary. James subsequently published a rebuttal, The True Law of Free Monarchies. It set out an opposing opinion on the duties of the subject to the king, and vice versa. He saw himself as one of God’s lieutenants on earth, and thus his power was the result of divine will, and not to be argued with.

James was also renowned for having favourites at court. Because these men exerted significant power they stimulated resentment amongst those less favoured.

These close relationships have led to speculation that James was gay, although it would be difficult to prove this conclusively.

Image gallery

Stained glass panel of James VI and I. Museum reference A.1966.174.

Stained glass panel of the duke of Buckingham. Museum reference A.1966.175.

Watch thought to have been given by James to the earl of Somerset. Museum reference H.NL 63.

Front of James VI gold 20-pound piece, Edinburgh, 1575. Museum reference H.C232.

Reverse of James VI gold 20-pound piece, Edinburgh, 1575. Museum reference H.C232.

Articulated figure of James VI on the throne. A lever at the back moves his arm which may have once held a sceptre. Museum reference H.KL 21.

James and the kirk

The Protestant Reformation in Scotland created a more Calvinist version of Protestantism, known in Scotland as Presbyterianism, in which all participants were said to be equal. James’s relationship with the kirk was somewhat fractious. Although he was a committed Protestant, he believed in a less extreme, Episcopalian version of Protestantism, in which the king was the head of the church, and ruled it through bishops. His idea of the church’s role more closely resembled that of the English Anglican church. An infamous incident occurred in 1596 when a Presbyterian minister, Andrew Melville, shook the king by the sleeve calling him but ‘God’s silly vassal’ in the religious sphere.

James’s ecclesiastical legacy endures in the King James Bible of 1611, which he commissioned.

Marriage

In 1590, James married Anna, the sister of the Danish king, Christian IV. After a rough crossing of the North Sea, she received a grand formal entry into Edinburgh. She was a powerful figure in her own right, and maintained good relations for Scotland with the rich Protestant Danish king.

Image gallery

James and witches

In 1590, as James was attempting to bring home his new Danish wife Anna, a storm blew his ship off-course near the coast of East Lothian. Subsequently, several alleged witches from North Berwick were arrested, tortured and executed, a process in which James took an active part. For a time, he was obsessed with uncovering witches, and in 1597 published a tract on them, Daemonologie.

Witch's collar, or jougs, formerly owned by the parish of Ladybank in Fife, 17th century. Museum reference H.MR 43.

Bloodfeud and the Borders

James was determined to assert his power as king, and to crack down on the ancient custom of bloodfeud. These violent disputes between families, and their large armed retinues, were often very long-running. Bloodfeud was seen as especially prevalent in the Borders (though it happened throughout Scotland), and James was to target the feud there. This was also part of his suppression of violence and cross-border raiding in the late 1590s. This was a time when it looked likely that he would succeed Elizabeth on the English throne.

The most famous of the Borders’ feuds was that between the families of the Scotts and the Kers.

Image gallery

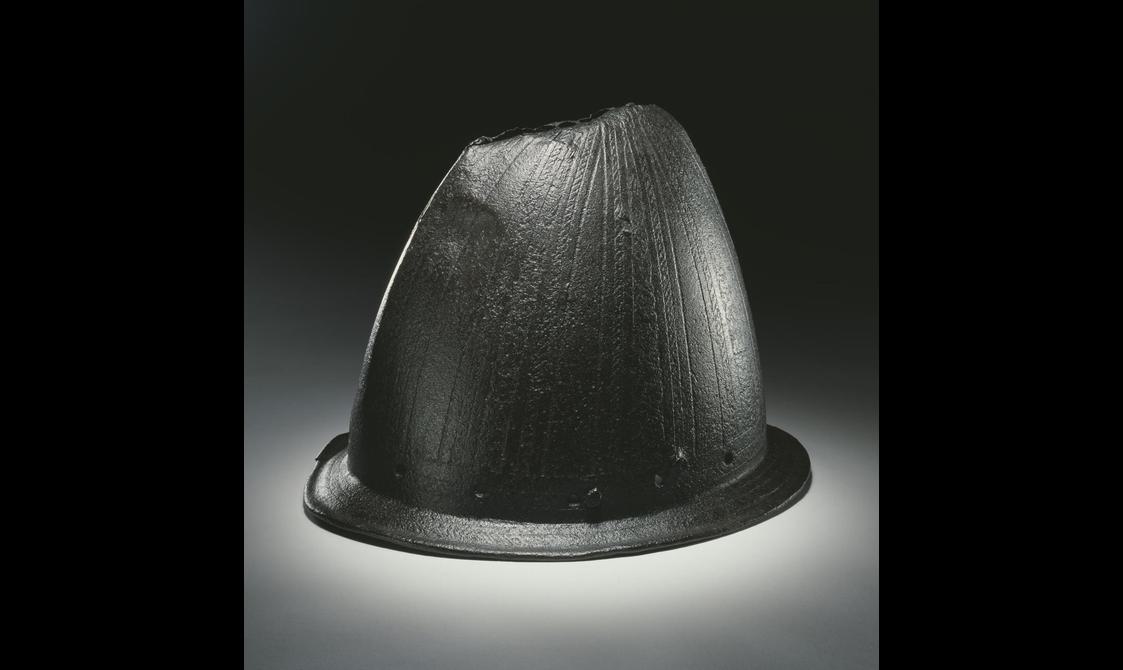

An iron morion helmet known popularly as a ‘steel bonnet’, headgear of the Border raiders. This was found at Ancrum, a stronghold of the Kers. Museum reference H.LN 50

Wat o’ Harden’s spurs. Museum reference H.ML 85.

Wat o’ Harden’s horn: Walter Scott of Harden would have used this bugle to call his men to his side in a raid or skirmish. Museum reference H.LT 45.

The Union of the Crowns

In 1603, James VI succeeded to the English throne on the death of his cousin Elizabeth I with no direct heirs. As the new James I of England, he rode south and was to spend almost the entire rest of his life in England, based at Whitehall. He is thus known to us as James VI and I.

James was very keen to promote the idea of union and friendship between the previously hostile England and Scotland. He called it a ‘blessed union’, one of ‘hearts and minds’.

Banner showing James VI and I’s coat of arms combining those of Scotland (the saltire, the unicorn, and the rampant lion in the top left dominant quarter), of England (the cross of St George, the three lions in the top right quarter), and of Ireland (the harp in the lower left quarter).

Return to Scotland

Despite promising on his departure to return every three years, James was only to return to Scotland once in 1617. Having professed a ‘salmon-like’ desire to return to the land of his birth, he came with a multitude of English and Scottish courtiers and councillors. He spent around three months touring his castles and palaces, and those of the great lords and lairds.

During this period, he presided over a meeting of the Scottish parliament, which famously rejected his attempt to get them to pass his ecclesiastical reforms. This became known as the Five Articles of Perth. Elite Scottish households prepared for the king's visit and there are several examples of objects and decoration made in case the king came to visit.

Image gallery

Ceiling boss of carved wood, with a unicorn carrying a Union flag, with traces of original paintwork, from Linlithgow Palace, Scotland, c. 1617. Museum reference H.KL 177.

Circular beech box containing a set of fourteen roundels or plates used at an entertainment given by Sir George Bruce of Carnock for King James VI: English, 1570 – 1620. Museum reference K.1999.528 C.

Circular beech box containing a set of fourteen roundels or plates used at an entertainment given by Sir George Bruce of Carnock for King James VI: English, 1570 – 1620, with inscription on the bottom, ‘Desert Plates used at an Intertainment given by George Bruce of Carnock to King James 6’. Museum reference K.1999.528 B.

Death and succession

James died in 1625 and was succeeded by his son, Charles.