A brief history of Roman Scotland

News Story

Many people think that Hadrian’s Wall marks the limit of the Roman Empire, but the Roman world stretched much further north than that. For almost 400 years, much of what is now Scotland was either inside the empire or an uncomfortably close neighbour.

Roman armies campaigned as far north as the Moray Firth. The Roman fleet sailed around Scotland and reached Orkney. Roman garrisons were stationed up the east coast at least as far as Stracathro in Angus, only 30 miles south of Aberdeen. Roman objects have been found all across the country, from Galloway to Shetland, showing the wide influence of the Empire.

The Roman armies tried to conquer Scotland three times, but each was short-lived. The history of Roman Scotland is a story of invasion and withdrawal. Scholars still debate why this happened. Were the local warriors too fierce, the landscape too rough, the conditions too difficult? Or did the rewards not justify the investment? Was it just too far away? When there were problems nearer to Rome, soldiers were pulled out of Britannia, leaving too small a force to hold the country.

The truth is a mixture of all these possibilities, and the influence of any one factor varied over time.

Image gallery

The Bridgeness distance slab c. AD 142, found at Bo'ness on the Firth of Forth near the eastern terminus of the Antonine Wall X.FV 27.

Coin of Septimius Severus found at Birnie, Moray.

Sestertius of Antoninus Pius, minted in Rome, AD140-144.

A gladius, the iconic weapon of the Roman legions, found at Newstead. Museum reference X.FRA 138.

Roman advances in Scotland

Campaigns into what is now Scotland started in earnest in the 70s AD. Under the emperor Vespasian and his sons, the governor Agricola led the legions deep into Caledonia. The Roman armies won a major battle at Mons Graupius, somewhere in north-east Scotland. But within a few years, demands for soldiers elsewhere meant they abandoned their conquests and pulled back.

They first withdrew to more secure territory in southern Scotland, and then to northern England between the river Tyne and the Solway Firth. This line was fortified under the emperor Hadrian, who ordered the now-famous Hadrian's Wall to be built on the Empire’s northernmost edge.

Hadrian's successor, Antoninus Pius, ordered the army to push north again. They occupied Scotland as far as Perth and built another wall. This time the wall was of turf and earth, between the Firth of Forth and the Firth of Clyde which formed a natural pinch point in the land. Today we call this the Antonine Wall.

A section of the Antonine Wall at Rough Castle, Falkirk, showing the earthen ditch that was in front of the wall itself.

Croy Hill, a section of the Antonine Wall where many Roman-era finds were made.

This too was short-lived. Before Pius’s death, plans were being made to abandon Scotland and refortify Hadrian’s Wall. This remained the northern frontier, apart from a brief period in the early third century when the northern tribes were causing considerable trouble. The emperor Septimius Severus and his son Caracalla led a huge army north to try to crush the troublemakers in the area of Stirling, Perth and Dundee.

The local tribes, however, had learned not to face Rome in a pitched battle. They used guerilla tactics to grind down the Roman army. Although the Romans established new bases, they couldn’t control the area with force.

Severus died in York in AD 211, and Caracalla left Britannia as fast as he could to head back to Rome. The history of Roman involvement in Scotland didn’t stop there. Even when Rome's armies were back on Hadrian’s Wall, he kept a careful eye to the north. After all, a good general always knows what his neighbours are doing.

With a combination of scouts, punitive raids, and diplomatic activities, the Roman world stayed involved in Caledonia until the Roman Empire crumbled in the fifth century. These relations with Rome were a key part of the early history of Scotland.

Map of probable and possible Roman marching camps in the late 1st century AD. Note the concentration in southern, central, and eastern Scotland and the absence of known Highland sites.

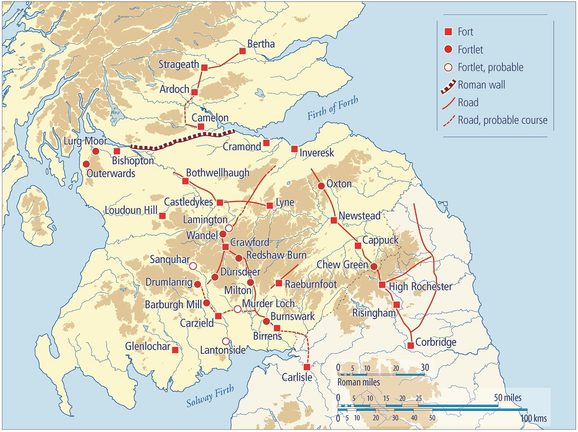

Map of Roman forts, fortlets, roads and the Antonine Wall in the mid-2nd century AD.

Roman warfare

The Roman army fought by different rules from the locals. Warfare in the Iron Age was generally a small-scale affair between different local groups or warbands. A lot of warfare was about prestige and protection rather than conquest. Bravery in a raid or a skirmish was a way of making a name for yourself. The dangers of raiding were a part of everyday life.

In stark contrast, the Romans fought to conquer. They came in overwhelming force, armed to the teeth. If local leaders sided with the Roman world, they were absorbed. If they resisted, they were crushed. This was a brutal army of occupation.

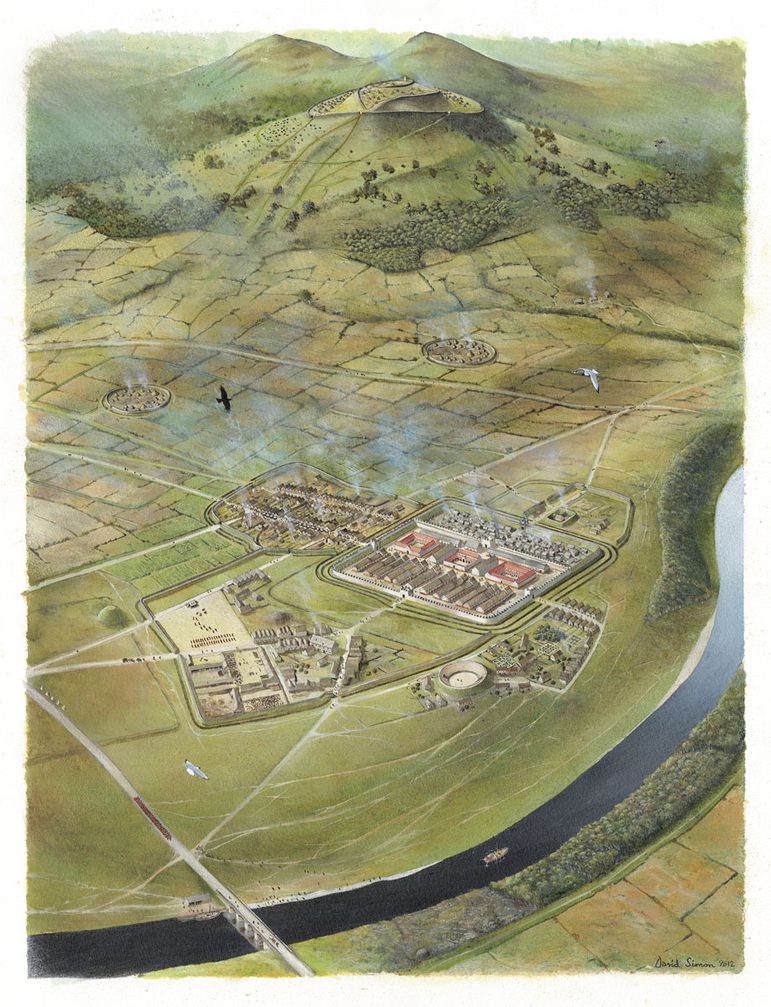

Artist's depiction of the Roman fort at Trimontium near Melrose in the Scottish Borders.

At the end of each day’s march, the campaigning troops built a temporary camp with a bank and ditch rapidly thrown up for protection. Remarkably, remains of these brief defences, used overnight or for a few days or weeks, still survive in the landscape today.

Once a general was sure that the enemy had been defeated, the troops were set to work in creating the network of occupation. This consisted of roads to allow men and supplies to move quickly around the country, with strongpoints spaced along them. Forts were typically garrisoned by 500 soldiers, while smaller fortlets were used in some areas to disperse Roman forces among a troublesome tribe.