A rare pectoral cross in the Galloway Hoard

News Story

Viking-age hoards are known for their large amounts of hacksilver. These are silver objects cut up and valued for their weight. Complete objects are rare from these silver hoards.

A well-preserved pectoral cross placed near the top of the Galloway Hoard was the first sign this was an extraordinary assemblage.

Pectoral crosses were worn on the chest as a display of Christian belief. Unusually, this one has a fine silver wire chain still in place, coiled around the cross and threaded through the pendant fitting. This suggests it had only recently been in use by the time it was buried.

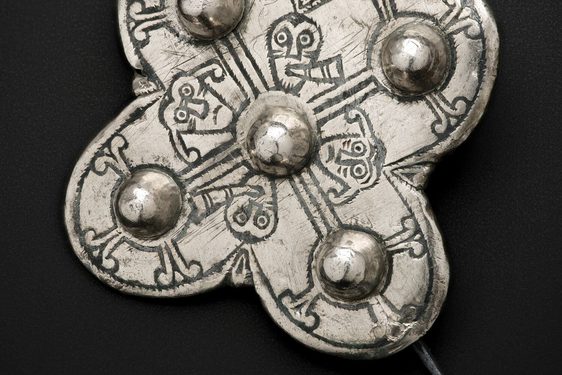

The shape of the cross immediately recalls depictions of the Christian cross in sculpture. It is an equal-armed cross, modified with circular armpits. This was a common feature of early medieval Insular (Northumbrian, Gaelic and Pictish) art styles. The back of the cross is undecorated silver. The front is decorated with several materials, requiring careful cleaning and conservation.

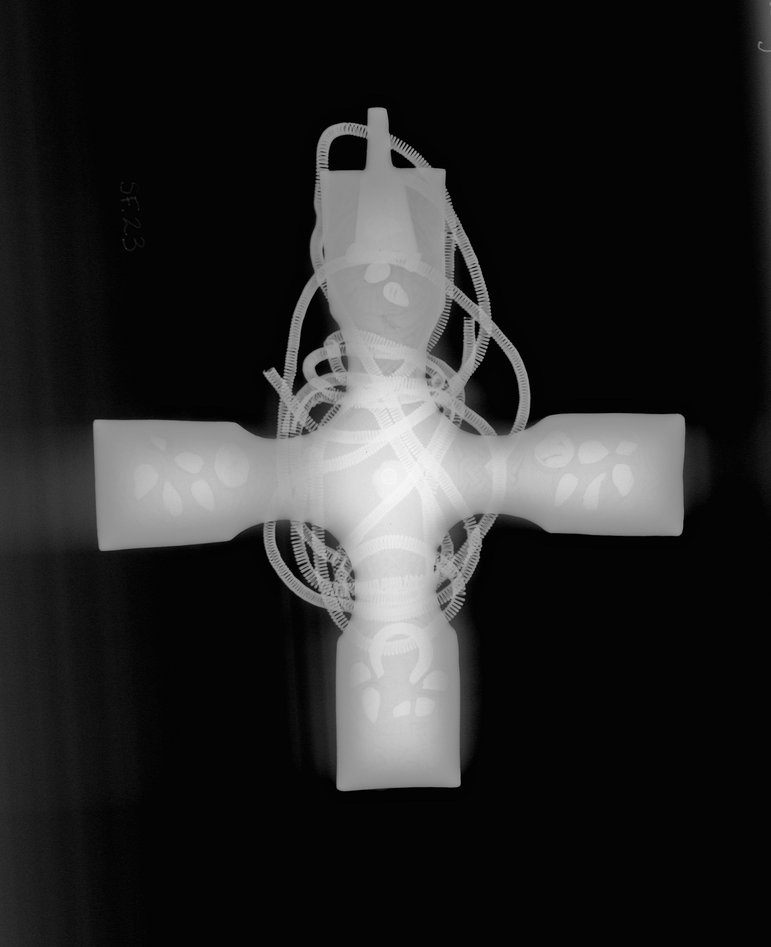

X-radiography prior to conservation showed the different parts of the cross and its ornament. At the head, a sturdy silver mount with a loop holds the suspension chain. At the centre, a large silver rivet once secured a large circular boss. This was removed before the cross was deposited in the Galloway Hoard. Patches of brighter white reveal denser material, in this case gold which was applied into cut out recesses in the silver surface. It revealed a mirroring of the design on the left and right arms.

A sacred object

After cleaning, it was clear that the Galloway Hoard cross is a supreme example of a late Anglo-Saxon art-style known as Trewhiddle style. This style was named after a late ninth-century hoard of metalwork from Cornwall. Its animal and plant forms are characteristic of this style.

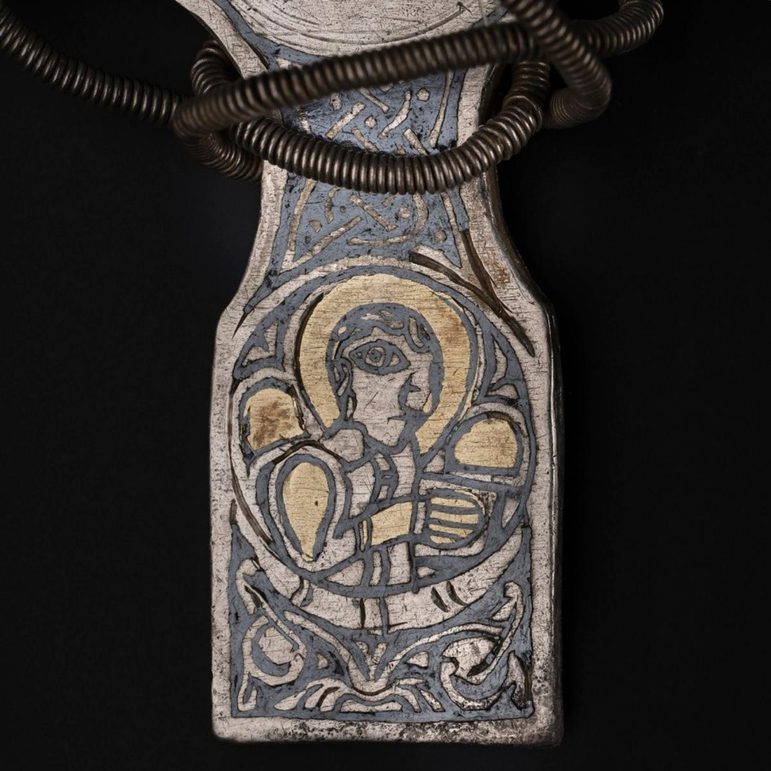

The gleaming silver surface was carved and then inlaid with pieces of gold. Both the silver and gold were then inlaid with black niello, a paste of silver and copper sulphide. The gold areas were used to pick out important features such as the wings and haloes of the figures on the cross arms.

Several objects from the Galloway Hoard were made in the same style, including the gold bird-pin and the silver disc-brooches. This use of figurative and naturalistic art differs from largely abstract ‘Viking-age’ decoration seen on the arm-rings in the Hoard.

In each of the arms of the cross are the symbols of the four evangelists who wrote the Gospels of the New Testament:

- Saint Matthew (bottom – haloed figure)

- Saint Mark (right – the winged Lion)

- Saint Luke (left – winged ox)

- Saint John (top – eagle)

Parts of their body, and in the case of Matthew, his halo, are picked out in gold with a black and white background. All four symbols of the evangelists hold a book representing their Gospel.

Each evangelist is framed within a roundel set in a complex design of sprouting foliage. The narrow, curved portions of the arms are filled with a tight interlace design shaped around the empty central circle. The lion and winged ox look inward toward the missing central setting. The lost feature at the crossing of the arms may once have held a depiction or symbol of Christ.

Revealing the cross

The variety of materials used and the fineness of the ornament presented unique challenges for conservation. Some areas were well preserved under thin layers of dirt and superficial corrosion. But others were badly damaged. In some areas corrosion had formed underneath the niello decoration. This pushed it to the surface, where it became extremely vulnerable and brittle. Some of the niello was also disintegrating, with the surface reducing to silver and forming into small curls.

The cross was conserved by removing dirt and corrosion working under a low-powered optical microscope. Hand tools like swabs with mild abrasives, cocktail sticks, scalpels, needles, brushes, and even porcupine quills, were used for removing silver corrosion and dirt without scratching the silver. Loose particles could then be brushed away. The surface tarnish was removed with a swab and an appropriate abrasive. The whole process was very time-consuming.

Overall, the cleaning process took conservator Mary Davis an estimated 80 hours: 50 for the cross, and 30 for the chain alone.

It’s a very grand object, made for an important individual, who had access not just to considerable wealth, but also to a goldsmith of outstanding skill and artistry; and it is a unique survival of high-status Anglo-Saxon ecclesiastical metalwork from a period when – in part thanks to the Viking raids – so much has been lost.

Leslie Webster, former British Museum curator and author of 'Anglo-Saxon Art'

Conserving the chain

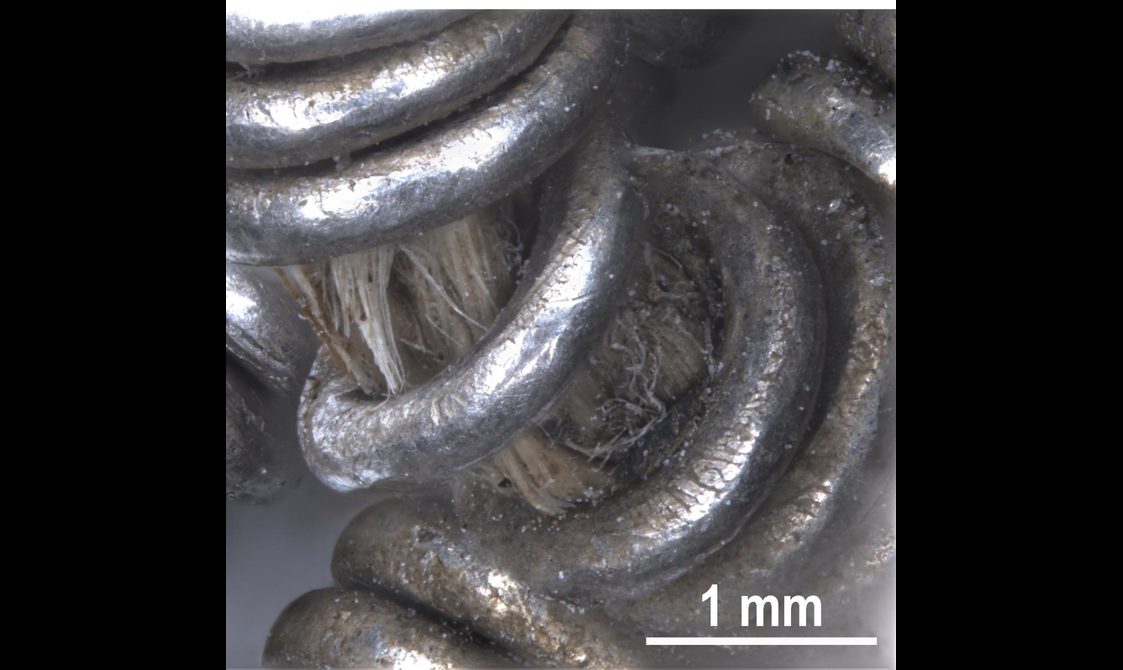

The silver chain is incredibly thin, delicate and mobile. This makes even basic cleaning time-consuming and labour-intensive.

It is made of sections of very fine coiled silver wire about 0.5mm thick. These are joined together by threading one section between the coils of the next. This allows the chain to look like a continuous spiral. There are very few visible gaps between the coils, but in some places the silver has stretched apart. It has also become quite brittle and the chain is broken in several places. The use of a porcupine quill carved to a fine wedge-shaped head was particularly useful for cleaning between the tight silver coils.

Where the coils have separated, it is possible to see remnants of a fine string running through the centre of the chain. A small surviving piece was removed with tweezers. When examined under the microscope this was identified as animal gut.

Animal gut string is made from the small intestines of domesticated animals like sheep or goats. It is extremely tough and versatile. It is still used for stringed instruments today as it can withstand very high tension. It would have been much stronger and more hard-wearing than other substances available at the time. A single piece could have been cut to the length of the chain. This provided a continuous central core to stop the sections of coiled wire from spreading apart like a spring when worn.

Image gallery

Desecrated or devotional?

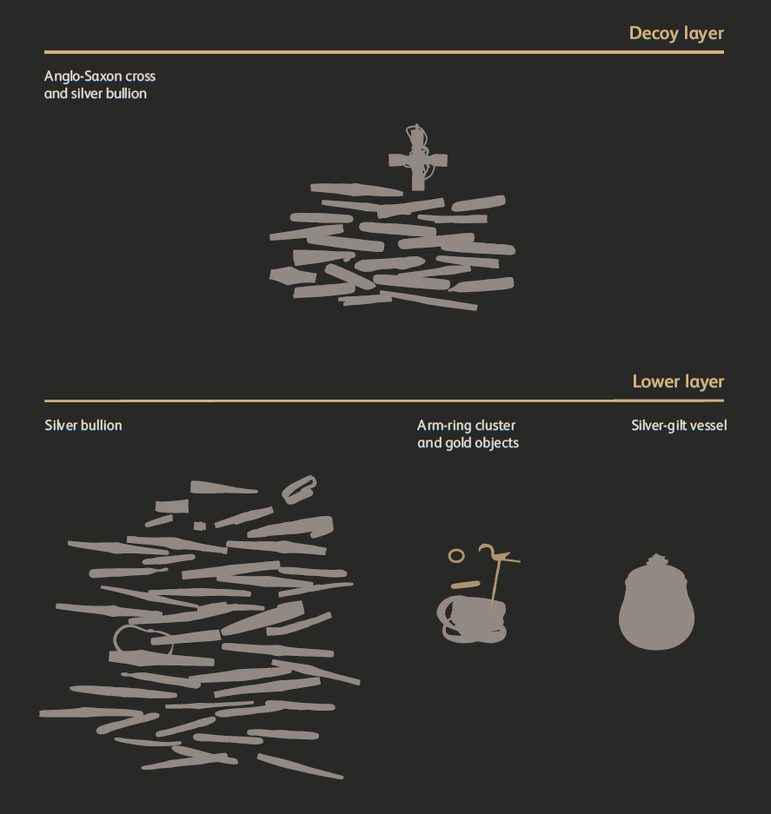

Everything about the pectoral cross is rare. Few Viking-age hoards have Anglo-Saxon material in them, and the presence of ecclesiastical material is rarer still. Of the crosses surviving from hoards, very few have suspension chains. This one was deposited as part of the upper layer along with only silver bullion in the form of ingots and arm-rings. The other Anglo-Saxon material in the Galloway Hoard was largely in the silver vessel buried beneath this. Why was this separate from the rest of the complete objects?

Much depends on how the cross was treated. This is why it was so important to conserve the cross with its chain coiled as found. The undecorated silver circle in the middle of the cross suggests a raised boss or gem setting which has been removed. Was this an act of desecration, or reuse of a valuable gem? After it was modified in this way, was the cross now just bullion to be melted down like the other hacksilver in the Hoard?

We can easily imagine this cross being robbed from a Christian cleric during a raid on a church – the classic stereotype of the Viking Age. But the Galloway Hoard was buried on what is now church land. Many silver hoards in Ireland were buried on church land in places where sanctuary could be claimed for possessions just as it could for people.

Many of the objects in the vessel, and the vessel itself, were carefully curated heirlooms, many wrapped in textiles. Is it possible the cross was placed not as a ‘decoy’ but as a protective offering for the Hoard as a whole?

Whatever its role in the Galloway Hoard, the cross would have been a valued possession. It would have been produced and worn by those with access to the highest quality ecclesiastical objects. It may have been worn as the badge of office for a high-ranking cleric, such as a bishop, abbot or abbess. Imagining how it came to be buried with the Galloway Hoard helps conjure the individuals behind this remarkable collection.