The Autumn harvest in 8 rural snapshots

News Story

Seasons of the year have always shaped how communities and people live. Farming and rural life was driven by the changing of the seasons. While the technology employed to do the work has changed, the tasks done in each season have largely remained the same.

Autumn is the season of the harvest, and is followed by a period of preparation. A variety of crops are reaped for food and for animal feed, and the soil is prepared for next year’s crops. Grain is stored and hay is baled to be used as animal bedding. As temperatures begin to fall, livestock farms get the animals ready for winter and young animals are taken to market to be sold at auction.

Our Rural Life collections have tools, machinery, craft objects, paintings, models and many more types of objects that relate to different seasons on the farm. Here are eight objects from National Museum of Rural Life that can tell us more about Autumn in Scotland.

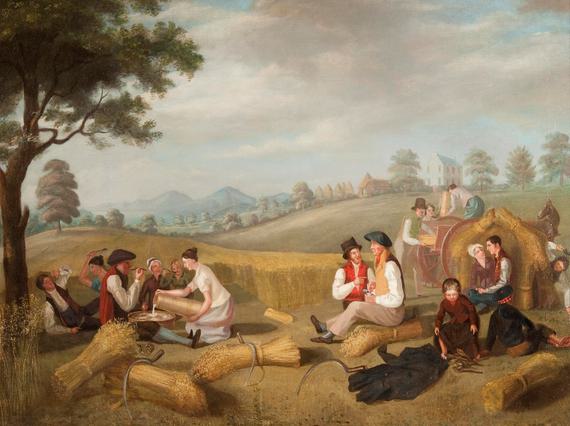

1. Everyone played a part

This oil painting shows a hairst, or harvest, at Auchindinny in Midlothian in the early nineteenth century. The artist has shown a team of workers who have set their sickles and sheaves of grain aside to stock up on food and refreshments. Reaping was physically demanding work. Although this painting shows an idealised portrayal of the hairst, it was a collective community task in which everyone, young and old, played a part.

The Hairst at Auchindinny, early 19th century, artist unknown, oil on canvas on display in the Tools Gallery at the National Museum of Rural Life. Museum reference H.OD 148.

2. Sickles then Scythes

The National Collection has a number of sickles and scythes used for harvesting crops. Several are on display in National Museum of Rural Life. Traditionally, the Scottish harvest was reaped by seasonal migrating workers. Groups of women from the Highlands and Islands would travel to the Lowlands, moving from farm to farm during the autumn months reaping the crops with a sickle. In the nineteenth century, the Highlander and the sickle were replaced with teams of Irish immigrants using scythes. Later in the nineteenth century the invention of the mechanical reaper began to replace both the sickle and the scythe.

Sickles and Scythes on display in the Tools Gallery at the National Museum of Rural Life.

3. Reaping the benefits of machinery

The invention of the horse-drawn reaping machine had a significant impact on agricultural practice in the nineteenth century and beyond. Some of its features were incorporated into early combine harvesters. The first reaping machine that was successfully adopted in practice was invented in 1826-28 by Rev. Patrick Bell, Minister of Carmyllie, Forfarshire. Bell created a reaper with a cutting bar that was based on the clipping motion of shears, and which was pushed from behind by two horses. This model of Bell’s Reaper is on display at National Museum of Rural Life.

Model of Bell’s Reaping Machine in the Study Store at the National Museum of Rural Life. Museum reference T.1865.79.93.

4. Flailing through Autumn

Flails were handtools used for threshing grain and consisted of two long parts - a wooden handstaff and souple (or beater). The flail would be swung and brought down with force on the sheaves of grain laid out on the threshing barn floor to separate the edible parts of the grain from the stalks. Flails were used from the earliest times in Scotland and in many other countries. Despite the development of threshing machines in the nineteenth century, the use of flails persisted on small crofts into the twentieth century. Threshing by hand was a very physical job on the farm and was usually carried out between Autumn and Winter.

Flails in the Study Store at the National Museum of Rural Life.

5. Threshing out

Threshing with a flail was hard work and required a lot of manpower and time, therefore machines began to be developed in the eighteenth century. In 1786 Andrew Meikle invented a threshing machine that could be worked by horsepower, wind or water. This large water threshing mill from Breck of Rendall farm, in Orkney, dates to c.1803 and is the earliest known surviving threshing mill in the world. This mill continued to be used until the 1960s and came to the National Collection in the 1980s.

Water Threshing Mill in the Tools Gallery at the National Museum of Rural Life. Museum reference W.1999.230.

6. Tattie baskets

The potato, or tattie, is a staple crop of Scotland. Tatties are harvested in October and although today this is largely done by machinery, it used to involve whole communities who would lift the tatties by hand. It was such an important part of the farming calendar in some regions of Scotland that children would be taken out of school for two weeks to help. Today, this activity is still marked by the ‘October Holidays’, but luckily for children they no longer have to take to the field. These baskets are known as tattie baskets or tattie sculls and were used to scoop the uprooted potatoes from the ground. Tattie sculls would be made of whatever was available locally – split wood, cane, willow – but were of roughly the same shape and size everywhere.

Two of 12 tattie sculls from Ewingston, East Lothian, 1920s. Museum reference W.1990.249.

7. Combining it all

The combine harvester was introduced to Scotland in the 1930s, but it took until after the Second World War before they were widely used by farmers. The first combine harvester used in Scotland was this example by Clayton and Shuttleworth, made in Gainsborough, Lincolnshire. It was purchased by the 3rd Earl of Balfour in 1932 for use on his farms in East Lothian. Combines were designed to harvest a variety of crops and ‘combined’ the processes of cutting, threshing and dressing them all at once, effectively replacing tools and machines that did these jobs in previous times. Today, combines are a common sight in Scottish fields between the months of July and October. Held at National Museum of Rural Life, our combine collection is one of the largest in Europe.

Clayton and Shuttleworth Combine Harvester in the Combine Store at the National Museum of Rural Life. Museum reference W.1999.200.1, W.1999.200.2.

8. A harvest celebration

So much effort goes into preparing the soil and harvesting the crops on a farm. So, it's no surprise that once the last sheaf was cut and the harvest had been successfully reaped, it was time to celebrate. Harvest celebrations and commemoration took different forms throughout Scotland and are steeped in folklore and local traditions. Festivities included drinking and eating, dancing and singing, and members of the community also made harvest plaits or knots like this one shown here. Traditionally, harvest plaits and knots took the last stalks of grain to be cut and bound or plaited them. They could be hung in the home or the barn, worn, or used to decorate carts.

Harvest Plait. Museum reference W.1970.20.