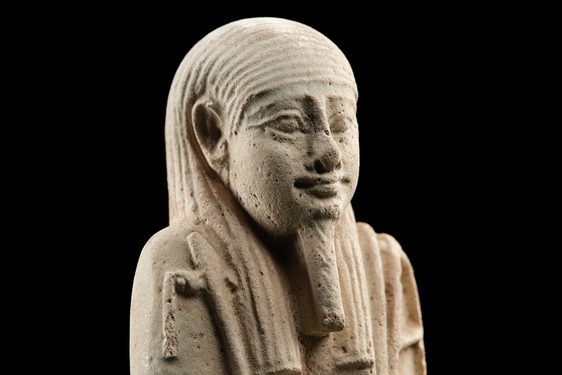

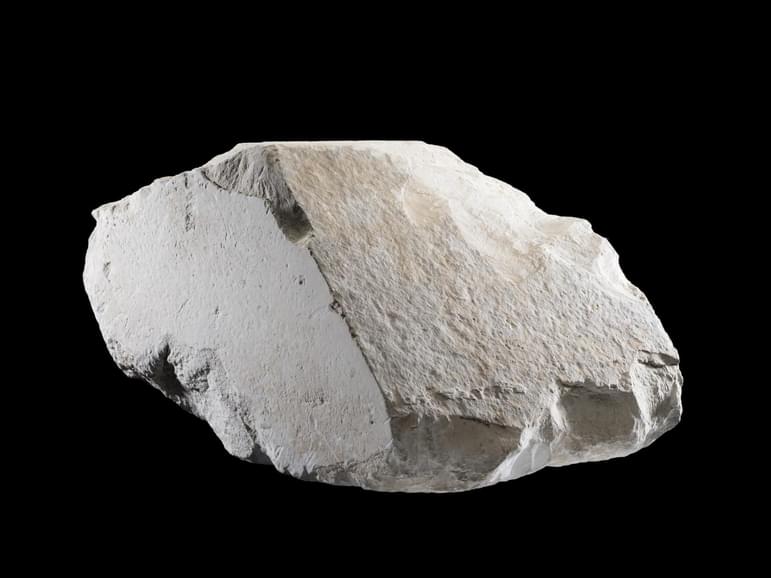

Casing stone from the Great Pyramid of Giza

News Story

This block is one of the few surviving casing stones from the Great Pyramid of Giza, built for King Khufu. It is the only pyramid casing stone on display outside Egypt.

Khufu was the King of Egypt around 2500 BC. He is also known as Cheops, the ancient Greek rendering of his name. King Khufu's biggest legacy is the Great Pyramid, the oldest and largest of the pyramids at Giza.

What was the casing stone used for?

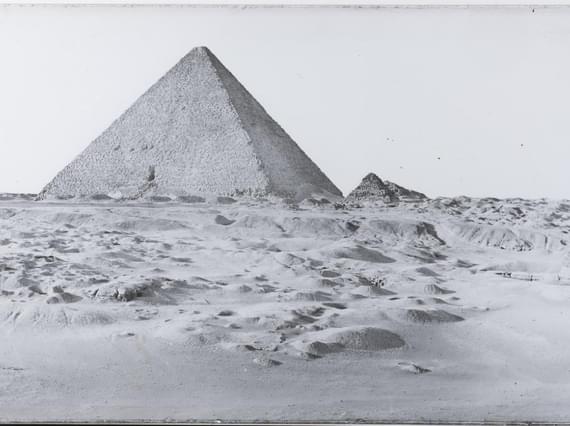

Around 5.5 million tonnes of limestone, 8,000 tonnes of granite (transported from Aswan, 800km away), and 500,000 tonnes of mortar were used to build the Great Pyramid.

The mighty casing stone formed part of an outer layer of fine white limestone. This outer layer made the sides of the pyramid completely smooth. It was polished until it shone so that the pyramid would have gleamed in the sun. The limestone casing blocks came from quarries at Tura 15km upriver from Giza.

The Great Pyramid casing stone, Giza.

How did the casing block come to the Museum?

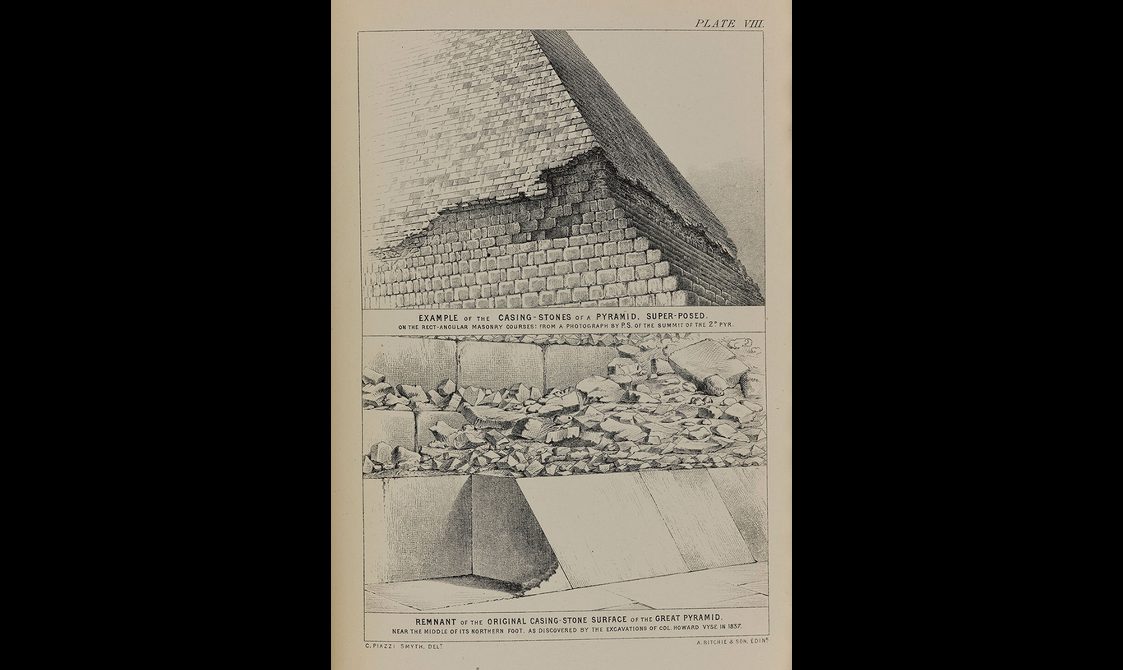

By the 19th century, most of the casing stones had been removed. They were used for other building work, although some can still be seen at the foot of the pyramid.

The stone came to the UK in 1872 as a result of work undertaken by Charles Piazzi Smyth, Astronomer Royal of Scotland. In 1865, Piazzi Smyth carried out the first largely accurate survey of the Great Pyramid. He was given official permission to carry out this work by the Viceroy of Egypt, Ismail Pasha. He received assistance from the Egyptian Antiquities Service and the Governor of Giza. When Piazzi Smyth returned to Scotland, he published many articles and books to share his results.

Piazzi Smyth had planned to do further survey work at Giza. However, ill-health led him to request the assistance of his friends Dr James Grant Bey and Waynman Dixon instead. Grant was physician to the Viceroy and a well-known figure in Egyptological circles in Cairo. Waynman Dixon was a structural engineer who was building a bridge in Cairo. Dixon and Grant carried out their work at Giza in 1872 with the permission of the Egyptian Antiquities Service, though local consent was not sought (it was not standard practice at the time to do so).

While working in Giza, they found a casing stone among the rubble at the base of the pyramid. It had been uncovered during road building work carried out at the base of the pyramid by the Egyptian government a few years earlier. Dixon undertook the transportation of the stone to Edinburgh for Piazzi Smyth.

Some interesting discoveries have been made in and about the Pyramids of Ghizeh by Mr. John and Mr. Waynman Dixon of London, assisted by the English physician in Cairo, Dr. Grant… Exploring among these rubbish heaps, Mr. Waynman Dixon lately discovered this loose specimen, just in time to save its being broken up and used in building near there...The stone has been sent to Professor Smyth.

The Graphic, Dec 7, 1872

Image gallery

Plate from Charles Piazzi Smyth’s publication 'Our Inheritance in the Great Pyramid' showing some of the casing stones still in situ at the base.

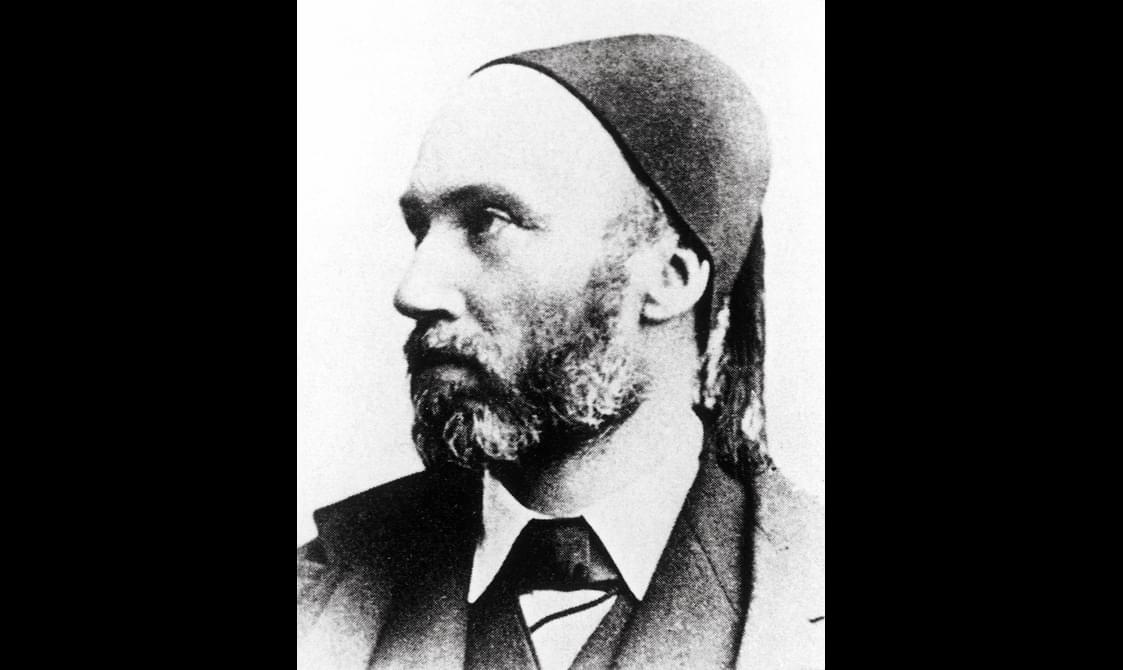

Charles Piazzi Smyth.

Glass lantern slide taken by Charles Piazzi Smyth showing Jessie Piazzi Smyth standing next to the sarcophagus in the King's Chamber in the Pyramid of Khufu.

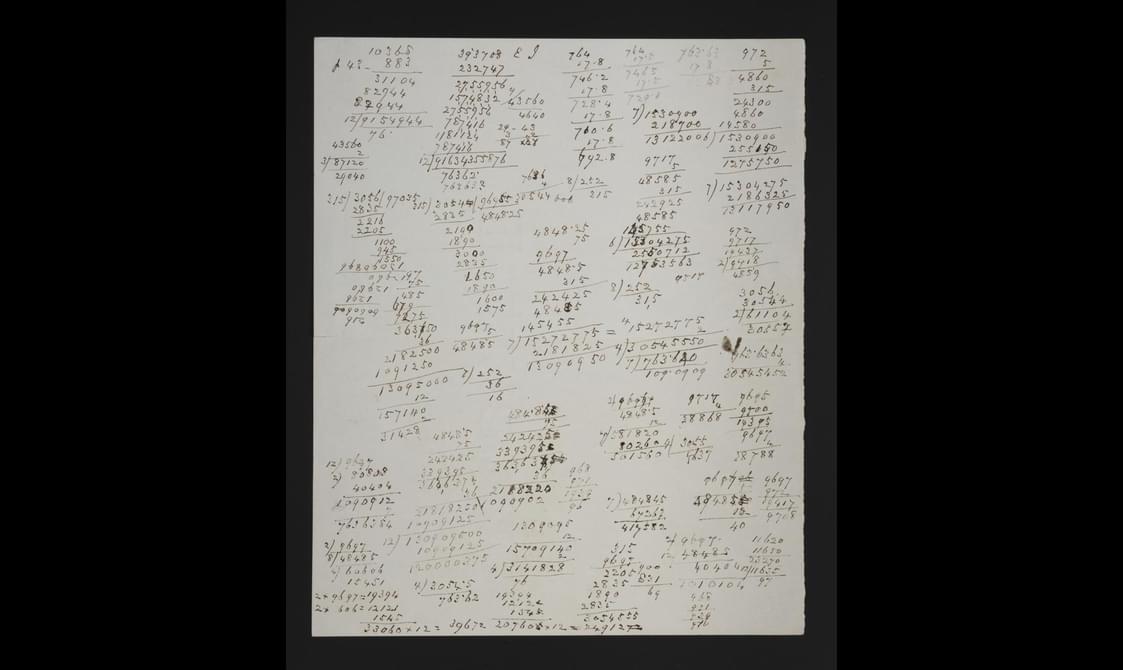

Glass plate photographic negative taken in 1865 by Charles Piazzi Smyth with handwritten notes 'Great Pyramid, its sepulchral hill, the Sphinx, &c, from hill top, south?'.

Who was Charles Piazzi Smyth?

Charles Piazzi Smyth (1819–1900) was the Astronomer Royal for Scotland. In 1865 he and his wife Jessie, a geologist, completed the most accurate survey of the Great Pyramid of Giza to date. They took thousands of detailed measurements and the first photographs of the pyramid’s internal chambers.

Before his interest in the Great Pyramid, Piazzi Smyth was already a pioneering scientist. He worked in the fields of high-altitude astronomy, spectroscopy, and photography. He was also responsible for instituting the one o’clock gun in Edinburgh. This signal helped ships in the Firth of Forth set their maritime clocks.

Piazzi Smyth decided that he would conduct a survey of the Great Pyramid when he found other surveys too inaccurate to use to test his theories. Like many Victorians, Piazzi Smyth was influenced by evangelical Christianity. He championed the existence of a ‘pyramid inch’, a unit of measurement handed down by God. This became a political argument. The French had just introduced the centimetre. Smyth hoped his work on the ‘pyramid inch’ would prove the superiority of the British inch. However, his theories were ultimately disproved. Nevertheless, his books and lectures inspired many other researchers to work in Egypt. This included the person whose survey work at Giza would disprove his theories! W.M.F. Petrie went on to become one of the most influential Egyptologists.

Charles Piazzi Smyth resigned as Astronomer Royal in 1888 and retired to Ripon in Yorkshire, where he died in 1900. He was buried at St John's Church in the village of Sharow, where his grave is marked by, of course, a pyramid.

The casing stone was initially displayed in a custom-made glass case in the library of the Royal Observatory of Scotland and residence of the Astronomer Royal. It was donated to the National Collection by the Royal Observatory, Edinburgh, in 1955.

Charles Piazzi Smyth's pyramid-shaped gravestone.

The pyramid casing stone (museum reference A.1955.176) is on display in the Ancient Egypt Rediscovered gallery at the National Museum of Scotland.

References

References for this article

Nature, Nov 28 1872, pp. 71-72.

Nature, Dec 26, 1872, p. 146.

The Graphic, Dec 7, 1872, pp. 530, 545.

Lightbody, David Ian, 2016, ‘Biography of a Great Pyramid Casing Stone’, Journal of Ancient Egyptian Architecture 1, pp. 39-56.

Piazzi Smyth, Charles, 1867a, ‘A Notice of Recent Measures at the Great Pyramid’, Transactions of the Royal Society Edinburgh XXIV, pp. 385-406.

Piazzi Smyth, Charles, 1867b, Life and Work at the Great Pyramid, vol. 1 (Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas), pp. ix, 4-8, 29-30.

Piazzi Smyth, Charles, 1874, Our inheritance in the Great Pyramid: including all the most important discoveries up to the present time (London: Isbister), pp. 489-492.

Piazzi Smyth, Charles, 1880, Our inheritance in the Great Pyramid: including all the most important discoveries up to the present time, 4th edition (London: Isbister), pp. 28, 29, 489-492.