Dunadd Hillfort: The seat of early medieval Scottish power

News Story

Before there was a kingdom called Scotland, the people known as the Scotti were just one group among many in the north and west of Britain. By the sixth century AD, the Gaelic-speaking Scots had built a strong and wealthy kingdom known as Dál Riata. Their most spectacular power centre was the hillfort of Dunadd. It rose up from the wetlands at the mouth of Kilmartin Glen in Mid Argyll.

Excavations at Dunadd across the 20th century uncovered hundreds of artefacts, most of which fall within the heyday of Dál Riata in the sixth to ninth centuries. They reveal aspects of war and violence, but also the arts of diplomacy and metalcraft, in early medieval Scotland.

War

The history of early medieval Scotland is often depicted as a constant battle for supremacy among different ethnic groups. In a time when historical sources are sparse, we are lucky to have two early records of Dunadd from Irish chronicles. The first was a siege in AD 682, and the second was a battle that would change history.

In 736 King Onuist son of Uurguist burned Dunadd and subjected the Scots to Pictish rule. A boar symbol in a recognisably Pictish style is carved into a rock panel near the summit of Dunadd, and may relate to this battle.

In its early medieval heyday Dunadd was a bustling, multi-purpose settlement. Hillforts were the most visible power centres of early medieval Scotland. This natural crag had seen some form of occupation since at least the Neolithic, and in the Iron Age it was used as a fort. In the seventh century AD a complex series of ramparts were added. This transformed the crag into a classic ‘nuclear’ hillfort made of several enclosed terraces. Dunadd became an undeniable statement of martial strength.

A great assemblage of weapons was unearthed from Dunadd. Parts of over thirty spears, four arrowheads (including two crossbow bolts), and a fragment of a sword were found. Early medieval weapons are very rare, and this is the largest collection from Scotland. Not all of these were remnants of past battles. Weapons and other tools were being forged and repaired at the site’s busy smithy.

Peace

Before and after its documented battles, hillforts like Dunadd were arenas for royal statecraft. Dál Riata was made up of several kindreds, each with their own ancestral territory. It has been argued that Dunadd was at the interface of these lands – perhaps even a ‘neutral’ place for rivals to meet.

On the summit of the hillfort stood a monumental roundhouse of stone. Leaders assembled here and strove to keep the peace with elaborate rituals and feasts. Proclamations could be made from above to the crowds gathered in the lower terraces. The footprint carved into the rock at Dunadd has been interpreted as part of the rituals for the inauguration of kings. In many ways, hillforts made kingdoms, not the other way around.

The earliest excavations revealed 54 stone querns or handmills, used for grinding grain into flour. They act as a reminder of the labour it took to feed the crowds which gathered here. The discarded animal bones from these feasts show that fine cuts of beef were hauled up the crag for these lavish events.

The other critical evidence of elite gatherings is broken ceramic vessels. These were almost entirely made up of pots, bowls, and jars imported from Gaul, in the Gironde valley of modern-day France. This ‘E-ware’ ceramic tells us they were drinking wine and consuming other exotic foods. In amongst this material were sherds of fine imported glass from drinking vessels.

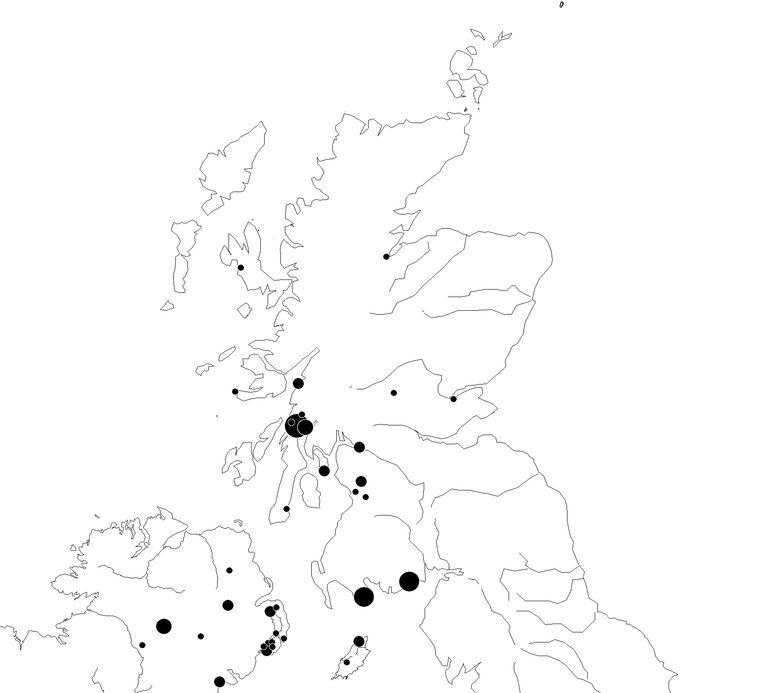

Dunadd has the largest collection of E-Ware ceramic in Britain and Ireland. It sits at the centre of a cluster of other finds of these imports in Mid Argyll. Its rulers seem to have redistributed these imports as gifts to neighbouring lords and allies. The distribution map puts Dunadd at the centre of a kingdom well-connected to the wider world, through both trade and diplomacy.

The melting pot

Dunadd was not only occupied by the Scots. These gatherings attracted visiting elites, foreign merchants and the best craftspeople. The metalsmiths of Dunadd were certainly well-connected. We can see this not only in what they made, but what inspired them. Amongst the metalworking debris are fragments of objects imported from far and wide, perhaps as models. Between the trading of objects and ideas, Dunadd became a centre for momentous artistic innovation.

One rare find is a piece of slate on which an artisan has sketched out the design of an elaborate pseudo-penannular brooch. The sketch has panelled terminals and settings for gemstones. It is similar to fine examples like the Hunterston Brooch and the Mull Brooch. This was a variation of the characteristic hoop-shaped dress fastener used as a badge of elite status across early medieval Northumbria, Wales, Scotland and Ireland. The remains of numerous clay moulds show that both penannular and pseudo-penannular brooches were being made at Dunadd.

The clay moulds also show that the Dunadd workshop had been in the business of casting brooches for centuries, from small (Fowler Type G) brooches found across western Britain, to bird-head terminals which are were most popular in Northumbrian England. Craftworkers at Dunadd were producing dress items from far beyond the fashions of Scots or even their Pictish and British neighbours. Over time, these artistic networks led to the creation of the blend of ideas we now call ‘Insular art’.

Image gallery

Gold and garnet stud from Dunadd, Argyll, imported from Northumbria, 600 - 700 AD. Museum reference X.1997.434.

Trial design on piece of slate for a penannular brooch, from the royal hillfort at Dunadd, Argyll, 575 - 850 AD. Museum reference X.GP 218.

Sheet bronze fragment with stamped ornament, from Dunadd, Argyll, imported from Northumbria, 600 - 700 AD. Museum reference X.1997.435.

Gilt copper alloy disc for a hanging bowl, from Dunadd, Argyll, 575 - 850 AD. Museum reference X.1997.481.

Gilt enamelled interlace disc from Dunadd, possibly a Germanic import, 575 - 850 AD. Museum reference X.HPO 267.

Clay mould for casting penannular brooch with bird-head terminals from Dunadd. Museum reference X.1996.293.653.

Church and state

In addition to its imposing hillforts, the kingdom of Dál Riata had one of the highest densities of Christian sites in early medieval Scotland. The occupants of Dunadd may have been Christian for most of the time the site was in use. One of the Dunadd rotary querns was marked with a simple cross of a kind used at the monastery of Iona. It has been argued that this quern was part of a gift or tribute from Iona. It suggests that flour made with this quern would be protected through the sign of the cross.

There are other signs of close ties between the fort at Dunadd and the Church. A sherd of E-ware ceramic from the monastery was likely traded or gifted from Dunadd. Beyond wine and exotic foods, these vessels also carried rare dyestuffs. These were likely intended for monasteries where they wrote manuscripts. At least one of the vessels at Dunadd contained Dyer’s Madder, a plant-based extract used for making purple dye. A fragment of a mineral called orpiment used for making yellow pigment was also found here.

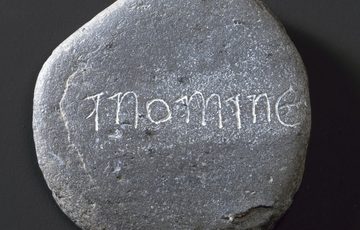

There are at least two other objects from the excavations which could have been Christian amulets. One is a small, handheld slate pebble inscribed inomine, an abbreviated invocation of the name of God. It is in the kind of script used in Insular manuscripts of the 7th or 8th centuries. The other is a plaque of mudstone incised with images of deer, eagles, and complex knotwork interlace based on the shape of the cross. It is perforated near the top, with wear suggesting it was suspended on a cord for a long period of time. Its art style suggests a tenth-century date, and it is one of the latest artefacts from the site.

Image gallery

Much more than 'just' a hillfort

Hillforts like Dunadd look at first glance like projections of military force. They make us imagine a time so dangerous that people needed to wall themselves up atop hills to stay safe. At Dunadd we see that its location was more than just defensive. It was positioned to channel different kinds of power. Being at the boundary between multiple kindreds of Dál Riata made it a shared place. Facing the sea opened it up to long-distance communication. Rising up from the mouth of Kilmartin Glen, it channelled the power of an ancient ritual landscape.

Just as its ramparts re-shaped the crag, Dunadd’s early medieval ceremonies re-made Scotland’s history.