Early Modern Scottish belief in 10 objects

News Story

These 10 key objects help paint a picture of belief and devotional practice in Scotland. By showing how people used and interacted with these objects, we get a glimpse into the everyday experience of faith in early modern Scotland.

In late medieval and early modern Scotland, religion was at the heart of daily life. This shaped how people thought and acted. Before 1560, Scottish people followed Catholic practices which used material expressions of faith. Objects were thought to have spiritual power, embodying the physical connection between believers and the divine.

In 1560, a religious Reformation occurred, and Protestantism replaced Catholicism in Scotland. The Protestant focus on the Word of God changed how people worshipped. Rituals became simpler, and objects were no longer viewed as inherently sacred. In the early years of the Reformation, objects and images relating to Catholicism were destroyed. Yet, some continuities remained in how people experienced and expressed their faith.

All these objects are on display at the National Museum of Scotland, in the Kingdom of the Scots Gallery. Visiting them in person offers a unique opportunity to appreciate their scale, detail, and physical presence. As you explore these objects up close in person or below, imagine how they were handled in prayer, used in worship, or interacted with in homes.

1. An iconographic finger-ring

This 15th century finger-ring is a small, intimate object of private Catholic devotion. It was designed to be used daily. It has two religious images engraved upon it. The Virgin Mary holds an infant Christ on the left, and a female saint, possibly Saint Barbara, is on the right. Saints played a vital role in pre-Reformation devotional practice. They were believed to have the power to intervene in people’s everyday lives. The Virgin Mary was often called upon for protection and could appeal to God on behalf of individuals. Saint Barbara was thought to protect against sudden death.

Wearing a ring engraved with religious figures was a way of maintaining a direct and personal relationship with them. The wearer would rub or touch the images on the ring while praying, creating divine connection through physical contact. Daily contact with the ring’s images reinforced the wearer’s personal faith and sense of divine protection.

Iconographic ring of silver-gilt depicting the Virgin and child on the left and a female saint on the right. From Hume Castle, Berwickshire, 15th century. Museum reference H.NJ 90.

Iconographic ring of silver-gilt depicting the Virgin and child on the left and a female saint on the right. From Hume Castle, Berwickshire, 15th century. Museum reference H.NJ 90.

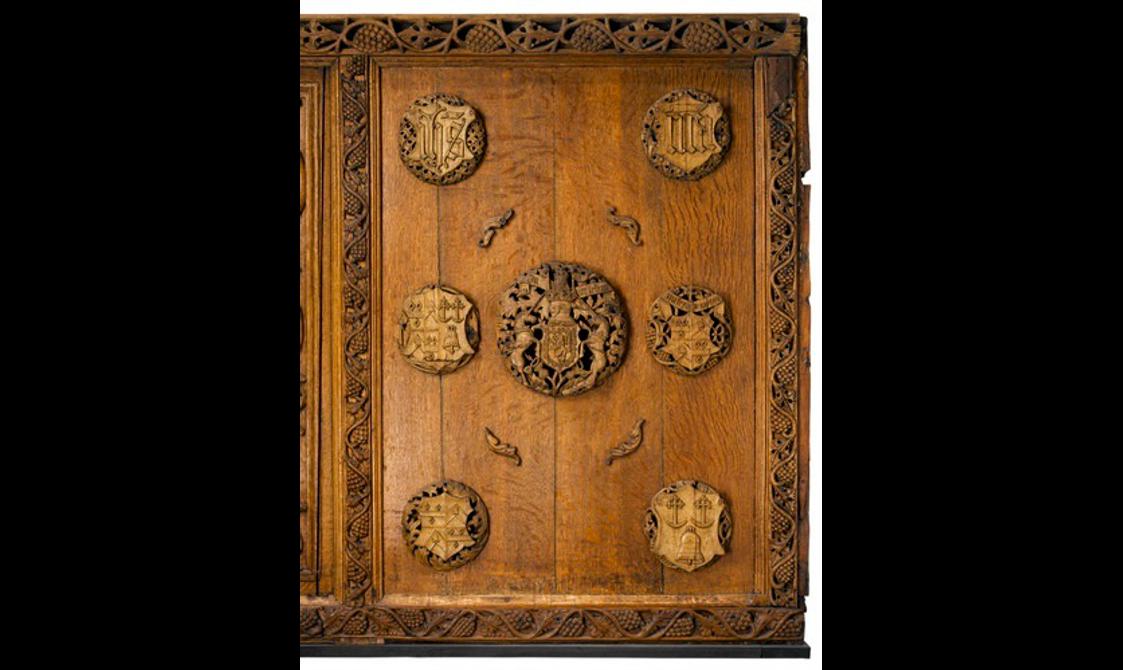

2. Carved Catholic wood panels

These seven carved wood panels were commissioned by Cardinal David Beaton in the 1530s. Beaton was murdered by Protestant rebels in 1546 for opposing the Reformation. But, the panels were saved by a member of Beaton’s family after his death and taken to their home, Balfour House, in Fife. Despite Protestant attitudes towards Catholic religious imagery, these panels remained on display there until the 1920s.

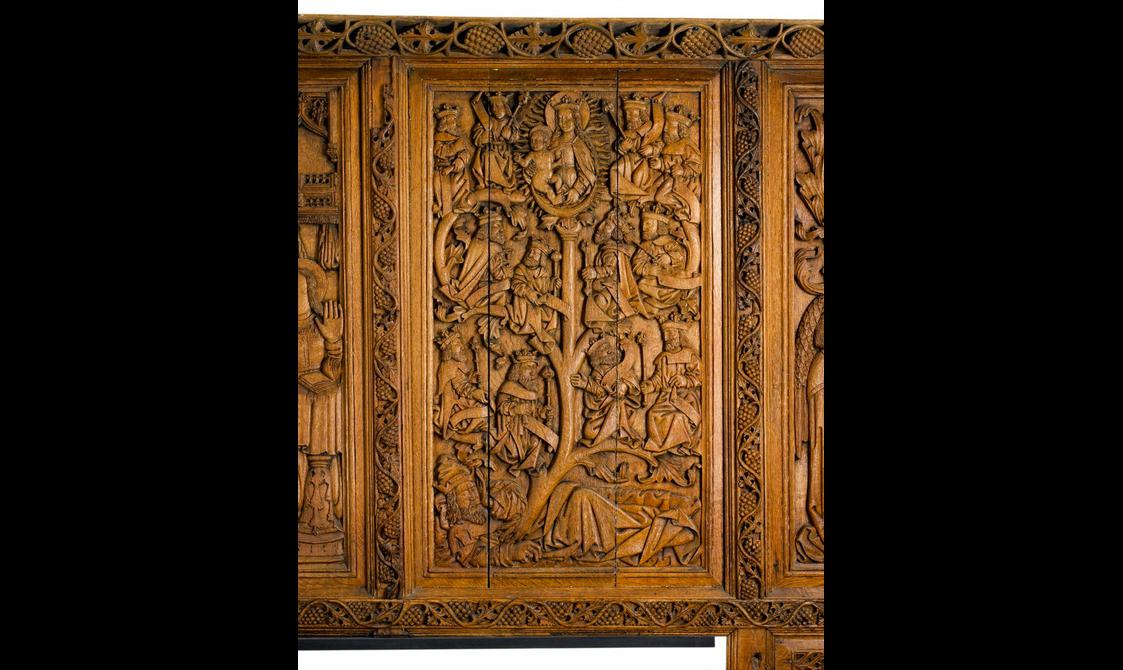

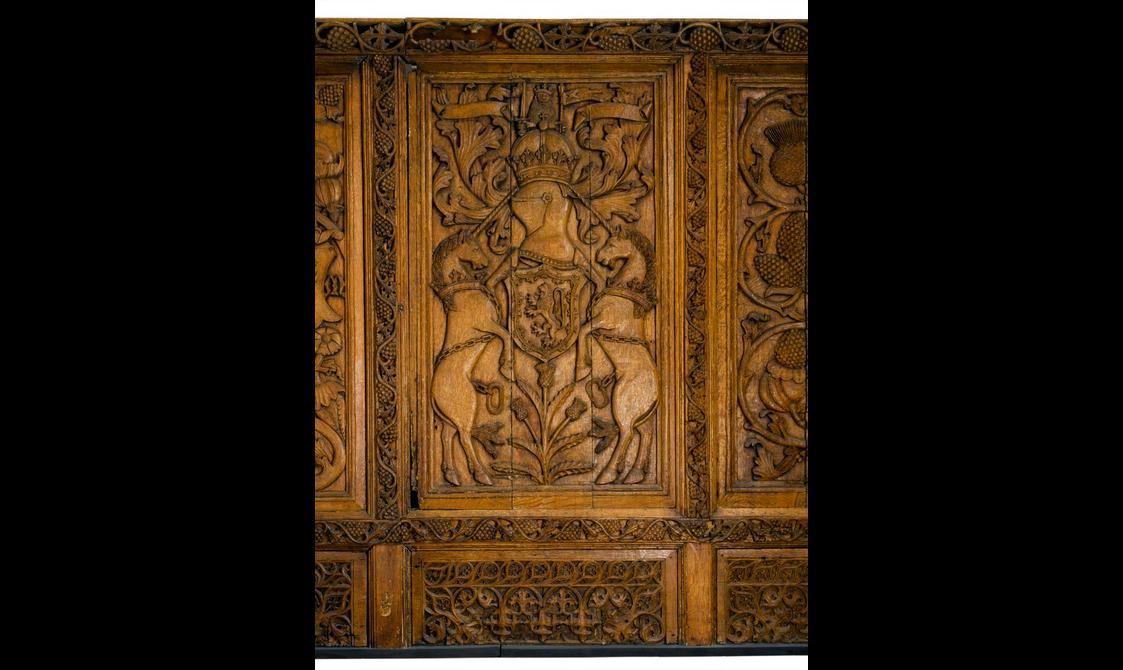

Due to their large size, these panels served as a projection of Beaton’s identity and as devotional aids. They show imagery related to Christ’s birth and lineage, alongside Beaton’s family heraldry. The first panel shows the angel Gabriel announcing to the Virgin Mary that she will give birth to Jesus Christ. The second represents Christ’s lineage. A tree emerges from the figure of Jesse, Christ’s ancestor. At the top, the Virgin Mary, holding the infant Christ, blossoms from the trunk. Next to this is a panel depicting the 'Arma Christi', symbols of Christ’s death, arranged like a heraldic shield.

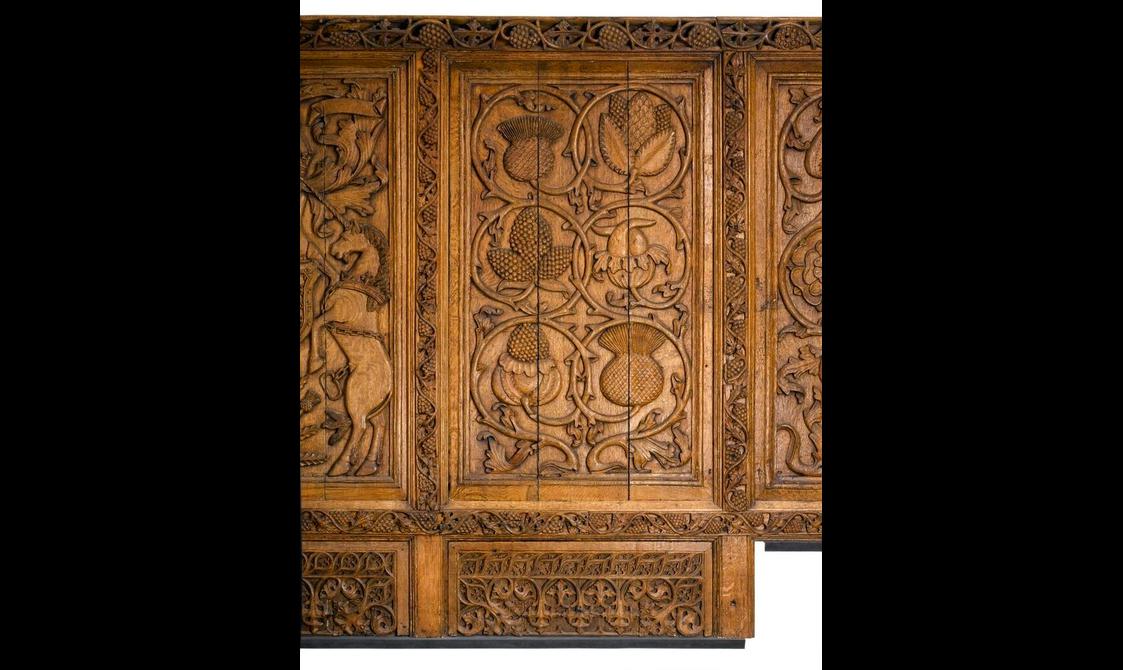

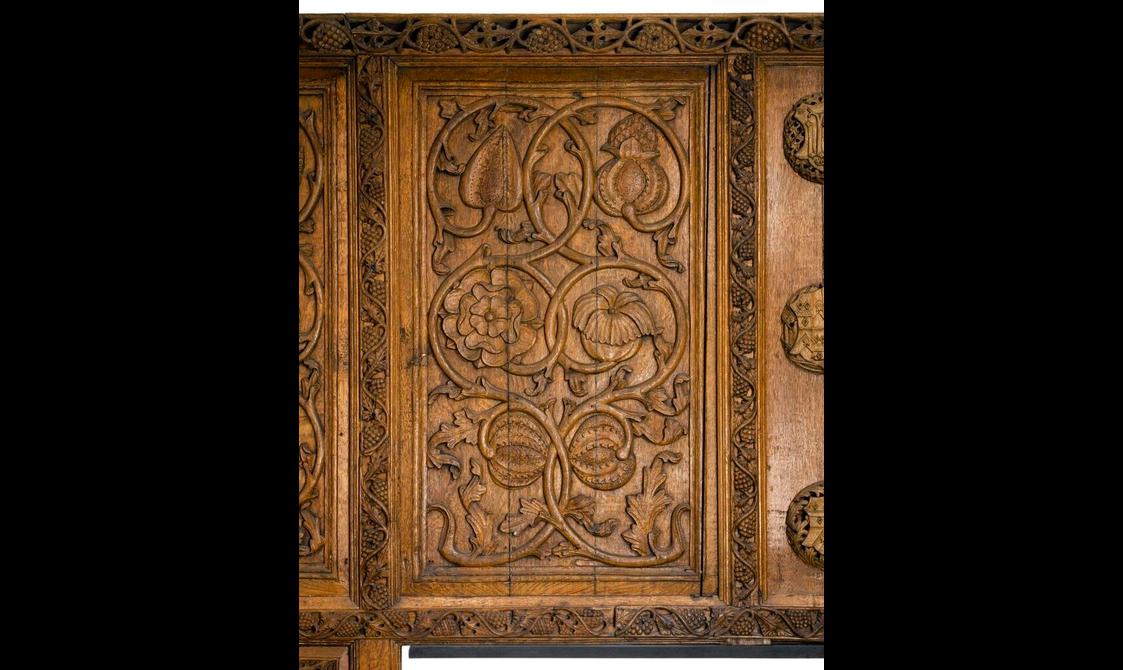

The remaining panels depict Beaton’s lineage, including his family’s Coats of Arms . These are intertwined with seedpods and flowers, celebrating fertility.

The blending of explicitly religious depictions with familial imagery may explain why these panels survived the destruction of religious materials in the early years of the Reformation.

Image gallery

Carved oak panel depicting the Annunciation, 1530s. Museum reference H.KL 222.

Carved oak panel depicting the Tree of Jesse, 1530s. Museum reference H.KL 222.

Carved oak panel depicting the Arma Christi, 1530s. Museum reference H.KL 222.

Carved oak panel depicting the armorial shields of Cardinal Beaton (top) and his parents (left and right), 1530s. Museum reference H.KL 222.

Carved oak panel depicting the Scottish coat of arms, 1530s. Museum reference H.KL 222.

Carved oak panel depicting flowers and seedpods. Museum reference H.KL 222.

Carved oak panel depicting flowers and seedpods, 1530s. Museum reference H.KL 222.

3. A 'jewel' associated with Mary, Queen of Scots

This intricate, double-sided pendant is believed to have belonged to Mary, Queen of Scots, who remained Catholic after the Reformation. It is gold with enamel inlays and measures less than 4cm high. Carved pearwood biblical scenes depicting the Crucifixion and Last Judgement adorn each side. The loops at the top and base suggest it likely hung from a rosary, a devotional tool of beads strung on a cord. Rosaries were worn on the body and used to count prayers by passing each bead through the fingers, creating a tactile connection to the divine.

As the believer turns the pendant during prayer, the two sides interact. The Crucifixion scene prompts the believer to reflect on Christ’s sacrifice. The Last Judgement serves as a reminder of divine justice. When considered together, the pendant invites the viewer to think about the connection between Christ’s sacrifice and their own moral choices in the face of mortality.

Gold and enamel pendant containing Biblical scenes of the Crucifixion and the Last Judgement carved from pearwood, 16th century. Lent by Alan W. D. McLean. Museum reference IL.2002.13.

Gold and enamel pendant containing Biblical scenes of the Crucifixion and the Last Judgement carved from pearwood, 16th century. Lent by Alan W. D. McLean. Museum reference IL.2002.13.

4. A Pilgrim's badge

This small badge is a spiritual souvenir, awarded upon the completion of a journey to a holy site. Saint Andrew, the Patron Saint of Scotland, has been cast into the surface of the lead. Found in London, this suggests that it was awarded after a pilgrimage to Scotland. Pilgrim’s badges were designed to be sewn onto hats or clothing as a way of commemorating the journey. These badges marked the pilgrim's spiritual achievements, and facilitated a community identity among the faithful. They reflect the community's commitment to Catholic practices and the veneration of saints.

Their association with sacred sites also meant that they were believed to carry divine powers.

When touched to a holy site or relic, the badge took on spiritual agency and had the capacity to heal and protect. Ritually rubbed, or used in prayer, these tokens became sacred in their own right.

Pilgrim's badge cast in base metal, rectangular with loops (one missing and one broken), with a design of St Andrew on his cross, found in Silvertown, London, 14th century. Museum reference H.KJ 320.

5. A charmstone with healing powers

Charmstones were believed to hold healing powers in pre-Christian Scotland. When Scotland adopted Christianity, instead of abandoning these stones, people began to integrate them into Catholic practices.

Elite individuals mounted charmstones in silver and suspended them on a chain. The charm could be worn as a protective amulet or ritually dipped in water. The water was given to people or animals as a drink to cure disease or prevent illness. The charmstones’ powers were activated by reciting verbal charms, like prayers, invoking saints. This blended traditional folk healing with religious practice.

After the Reformation, objects and practices relating to sacred intervention in the material world were deemed superstitious. However, charmstones endured into the 19th century. Deeply rooted in local tradition, the ongoing use of charmstones in post-Reformation Scotland reveals the tension between official religious doctrine and personal belief in the healing power of special objects.

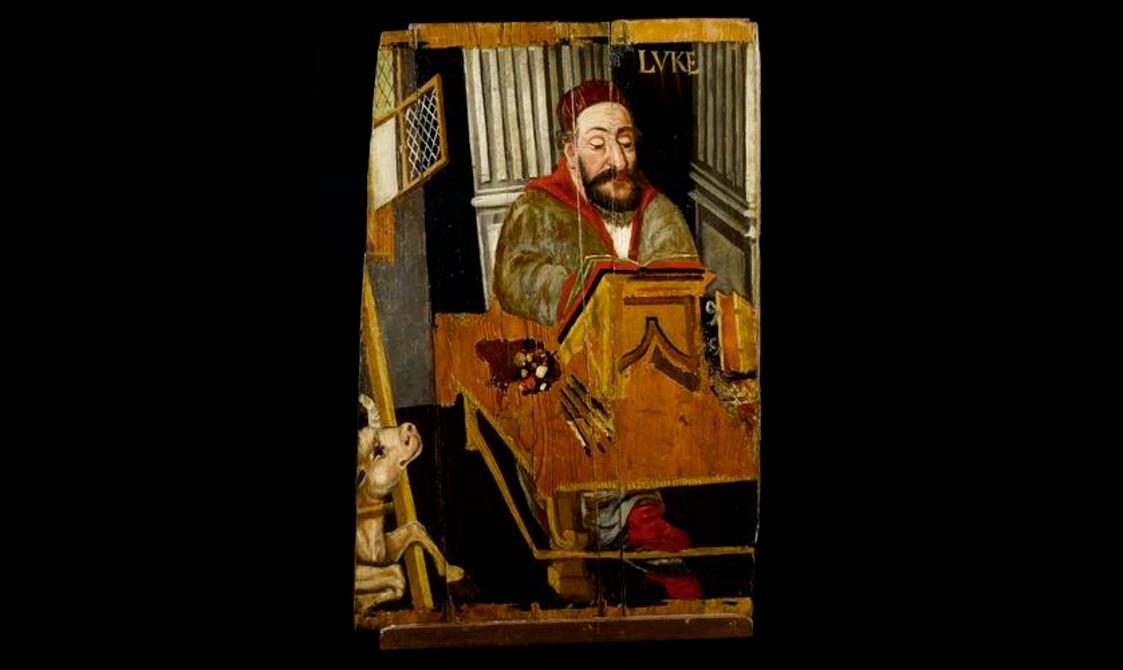

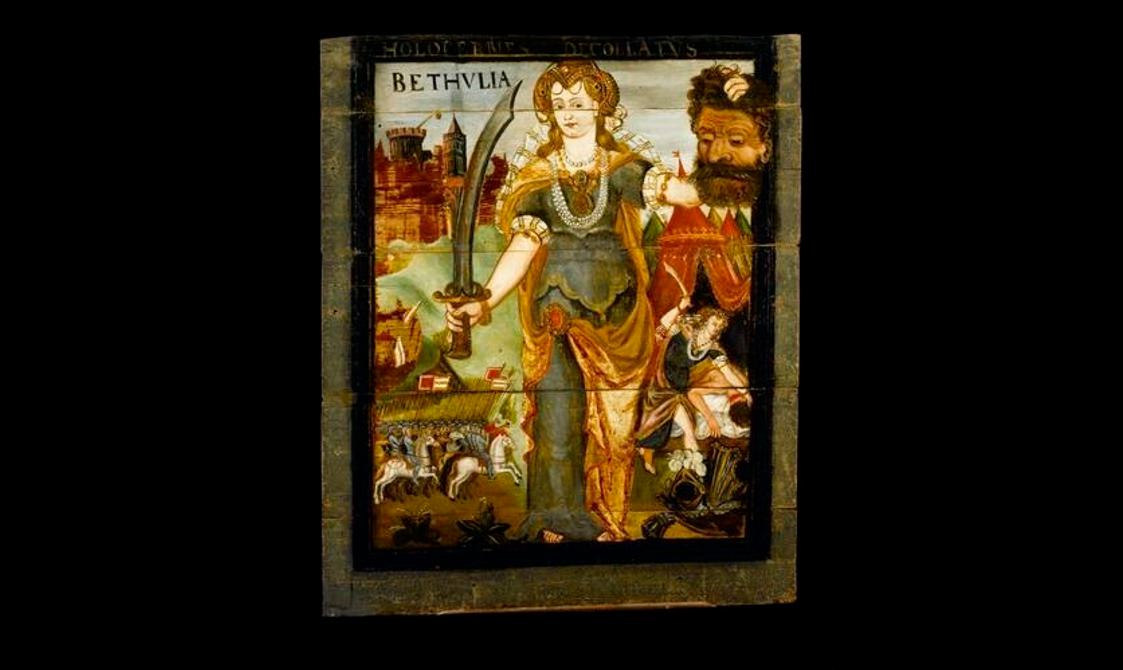

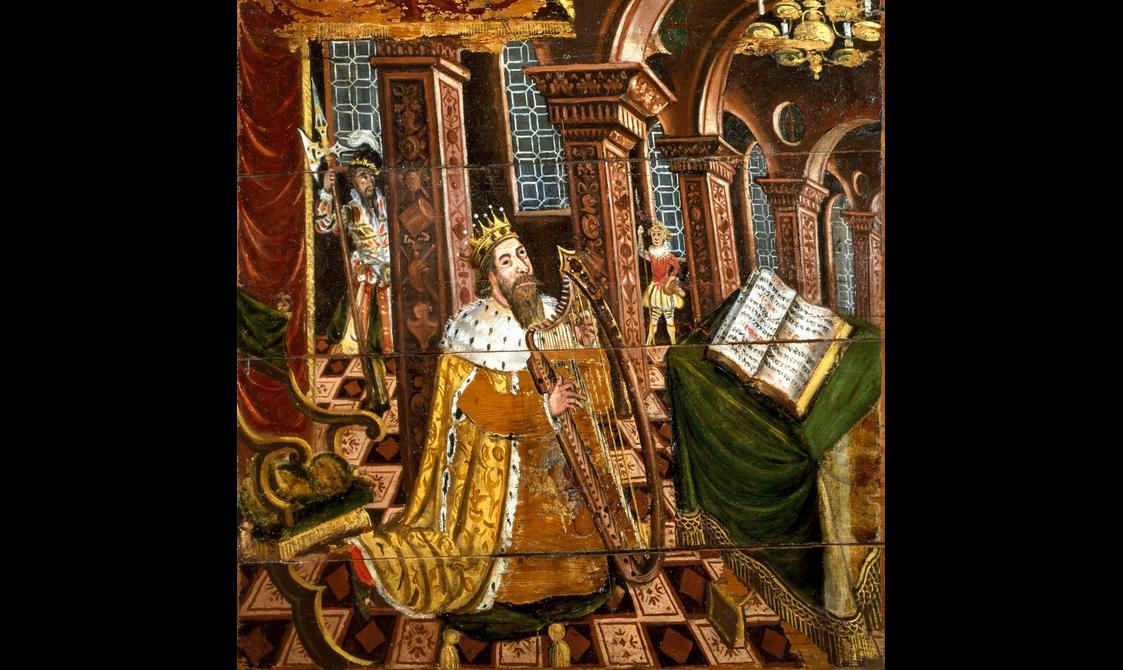

6. Painted ceiling panels

There is a misconception that post-Reformation Scotland was a colourless place. This comes from the promotion of the Word of God over visual representations of biblical stories. However, these panels were commissioned after the Reformation by a staunch Protestant for his Edinburgh home. Painted in the in the 1620s, they were once part of a decorative ceiling in the Gallery at Dean House, a space used to entertain guests and gather the family.

Reading scripture and listening to preaching were the primary ways of experiencing faith in post-Reformation Scotland. But, religious decoration remained present. Images of saints and scenes from Christ’s life were thought to be idolatrous. However, Old Testament stories were considered acceptable subjects, because they were viewed as historical narratives teaching moral lessons without the risk of idolatry. These brightly coloured panels animated the space and provided spiritual guidance to people in the Gallery.

Image gallery

Painted ceiling panel depicting St Luke, one of seven from Dean House, Edinburgh, probably by a local artist, 1605 – 1627. Museum reference H.KL 68.

Painted ceiling panel depicting Judith with the head of Holofernes, one of seven from Dean House, Edinburgh, probably by a local artist, 1605 – 1627. Museum reference H.KL 71.

Painted ceiling panel depicting Abraham and the Sacrifice of Isaac, one of seven from Dean House, Edinburgh, probably by a local artist, 1605 – 1627. Museum reference H.KL 69.

Painted ceiling panel depicting King David playing his harp, one of seven from Dean House, Edinburgh, probably by a local artist, 1605 – 1627. Museum reference H.KL 70.

7. Communion beakers

The Lord’s Supper became central to the collective practice of religion in post-Reformation Scotland. The ceremony was conducted in the Kirk to commemorate Jesus’ Last Supper. It involved the sharing of bread and wine as symbols of His body and blood. The congregation drank wine from communal cups and shared bread. The Lord’s Supper fostered both individual and collective expressions of devotion, providing spiritual nourishment and an opportunity for reflection.

With the change in ritual practice, new cups were needed to involve the entire congregation. This led to elite members of the congregation commissioning and presenting cups to the Kirk. Gifting these decorated vessels was a personal act. Many like this example have the donor’s name engraved on the cups. The gift demonstrated their elite social status and wealth in the community, and secured their legacy as a devout member of the church.

Silver communion beaker presented to Ellon Kirk, Aberdeenshire, by John Kennedy of Kermuck and his wife Janet Forbes, made in Amsterdam, 17th century. Museum reference IL.2010.39.1.

Silver communion beaker presented to Ellon Kirk, Aberdeenshire, by John Middleton, burgess of Aberdeen, made by Walter Melville in Aberdeen, 1642. Museum reference IL.2010.39.2.

8. A Covenanter's token

These penny-sized lead tokens were used by Covenanters to access secret religious gatherings. The Reformation in Scotland was not universal. Throughout the period different Protestant factions fought for control. Covenanters were a group of people who swore to uphold the principles of Presbyterianism against Royal religious intervention in the mid-late 17th century. While their voice was supported by Scottish Parliament against Charles I, with the Restoration of Charles II their ideas about the relationship between church and state were seen as rebellious.

The small size of these tokens allowed them to be carried discreetly in dangerous circumstances. They would be shown as admission to religious meetings often held outdoors or in private homes. They are usually cast with words, such as the phrase ‘I am the vine’. This quote evokes Christ’s connection with his followers, symbolizing spiritual unity.

Covenanter’s token inscribed 'I am/the vine', Scotland, 17th century, obverse. Museum reference H.1995.607.

Covenanter’s token inscribed 'I am/the vine', Scotland, 17th century, reverse. Museum reference H.1995.607.

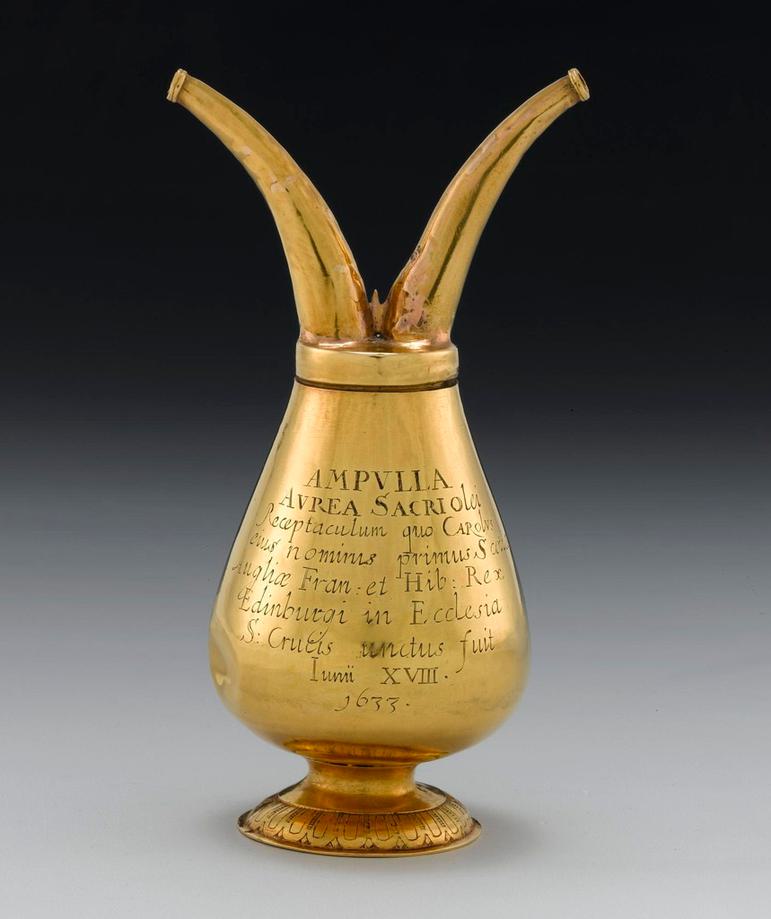

9. An ampulla used in a royal coronation

This gold ampulla, crafted to hold holy oil, played a central role in Charles I's 1633 coronation in Scotland. The ritual of anointing during coronation symbolises the divine authority of the monarch. The senses of smell and touch enhanced the experience for those taking part in the ceremony. The ampulla embodies an intimate, elite form of worship that reinforced the monarch's personal connection to divine authority.

Anointing of the monarch was a practice adopted in the Anglican coronation ceremony with Catholic roots. Charles’ coronation was the first time that this ritual had occurred in Scotland since the Reformation. Charles’ attempts to alter religious practice in Scotland were rejected by Presbyterians. The discord which resulted from these changes led to the Covenanting wars and can be linked ultimately to the regicide in 1649. In addition to rejecting the Anglican rituals as too Catholic, Presbyterians refused to recognise the monarch as head of the Kirk. The ampulla demonstrates the tension between the monarch’s personal faith, imposed upon the nation, and the disparate beliefs of the Scottish people. It not only held holy oil but also carried the weight of political and religious conflict.

Coronation ampulla of gold which held the sacred anointing oil for the coronation of Charles I at Holyroodhouse on 18 June 1633, possibly made by James Denniestoun, 17th century. Museum reference H.KJ 164.

10. Travelling Chalice

Not all people in Scotland followed Scotland’s Protestant faith. A small percentage of Scottish people remained Catholic, despite the threat of persecution. Priests operated secretly, often moving between hidden locations to perform Mass. Travelling chalices, small and portable, were central to this covert worship. In a Catholic Mass, the chalice holds wine that, during the ceremony, is believed to become the blood of Christ.

This example, like many in Scotland, can be taken apart at a moment's notice. The bowl of the chalice unscrews from the stem and can be inverted over it. This enabled the Priest to easily carry and conceal the chalice as they travelled across Scotland. Due to their small size, worship with these chalices was intimate. Conducted in private rooms, or sometimes outdoors, worshippers gathered fully aware of the dangers. In these secret gatherings, the chalice became a symbol of faith, transforming ordinary spaces into sacred sites for worship in the face of suppression.

Travelling Chalice. Museum reference H KJ 115.