Fashion and folklore of the Arnish Moor man

News Story

On the Isle of Lewis, in the early 1700s, a young man was mortally injured in mysterious circumstances. His body was buried just off the main road.

Over 300 years later, his clothed remains with a few small possessions were recovered, preserved in the peat.

18th century men's bonnet, jacket and stockings that were found preserved in peat.

The discovery

The man was found on 23 May 1964, just off the main north-south road from Stornoway by the turning to Grimshader. He was found by brothers John and Donald Macleod of Crossbost, Lewis, who were digging into a peat-bank when they came across a burial. On the discovery, they later said “To put it mildly, we both got a bit of a shock”.

After alerting the local police, it was established that this was not a recent death. The style of his clothing suggested instead that the body had been in the moor since the early 1700s.

Forensic analysis in the 1960s revealed that the person was a young man, around 20 to 25 years old and 1.64m tall. A fracture to the back of his head led at the time to a suggestion that he had been murdered.

His clothing and personal possessions were given into the care of National Museums Scotland. They are remarkably well-preserved, which gives us a rare insight into the type of dress being worn in the Outer Hebrides in the early 1700s. Through studying the fabrics, we can learn more about woven cloth and its making.

Questions remain unanswered over the man's identity, and the reason for his death and burial. Several local oral traditions have grown up about the events, and the existence and fate of his possible assailant. Supernatural sightings have also been reported.

18th century knitted brown man's bonnet. Museum reference K.1997.1115 F.

A traditional knitted bonnet

The first item found was the bonnet which remains in good condition. It is a traditional Scottish knitted bonnet, round in shape, and made of a firm felted wool that is now brownish green in colour. Dye analysis shows the presence of indigo, which suggests the bonnet used to be dark blue. Around its rim is a row of red wool knots at two-stitch intervals, which created a pattern like that of the red-checked bands that became popular later on in the 1700s.

Stylish outerwear

The man was wearing a long thigh-length jacket. It was fitted over the chest but flared out from the waist, with a central back seam, and a vent. This design allows us to date it to the early 18th century. The jacket was made from a woven woolen cloth that is now stained light brown by the peat it was buried in. It is likely that the cloth had been produced locally, even possibly by the man’s own family. The jacket was fastened with eleven cloth ball buttons running from the standing collar at his neck to his waist. Further buttons secured his cuffs and the one large pocket on the left hand side.

Originally it must have been quite a stylish garment, but it is now showing signs of much wear. The jacket has been repeatedly mended with patches of differently patterned cloth. A lining made from another garment has also been re-used.

Underneath there is an equally stylish but longer-length shirt, made in a more finely woven material of a similar light brown colour. It may have been made by a tailor, its buttonholes being neatly stitched, and the cuffs and collar lined. It’s quite a superior garment. In contrast, the undershirt that lay beneath it is much poorer quality. It's made from a variety of scraps of material and is very ragged in condition.

No breeches were found with the body. Instead long woven wool stockings or leggings remain and would have covered the lower legs, held up by cloth strips just below the knee. Perhaps the man was wearing a plaid for travelling, wrapped around his hips, which had been removed on burial? Alternatively, he may have been wearing something like linen drawers which would have disintegrated over time.

Image gallery

18th century menswear jacket inside with plaid fabric and stitching repairs. Museum reference K.1997.1115 A.

Fabric on 18th century menswear jacket inside showing repair stitching on seams. Museum reference K.1997.1115 A.

Fabric on 18th century menswear jacket inside showing repair stitching on the side vents. Museum reference K.1997.1115 A.

Mended with care

The many tiny hand stitches suggest the care that went into keeping the jacket wearable. This gives us an intimate look into its life and that of its owner and his loved ones. Perhaps the stitches are the work of his mother or grandmother or sisters; or maybe the jacket had been handed down by an older male relation?

Possessions of Arnish Moor man including comb and spoon.

The young man's possessions

The young man was carrying a small woolen bag. The bag is made of striped woven cloth, with a tie of lighter coloured material attached to the top to wind around to fasten it. Inside was a wooden comb, probably made of birch. It has fine teeth on one side and coarse on the other, many of the fine ones now missing. Alongside this was a well-used and mended horn spoon. He was also carrying two quill pens.

Who was he?

While we don’t know his identity, his clothing and possessions give us a few clues to the kind of person he was. The clothing is a mixture of good and poor quality. The bonnet and the outer clothing visible to others gave the man a better appearance than what lay below. The stockings too had been extensively patched, with rags tied around the right heel to cover a hole. He was man of limited means, but he was someone that cared about his appearance. His clothing was often repaired, and he had a comb. The care taken to mend his spoon signals that this was someone who looked after his possessions.

He was also educated to some degree, given the presence of the quill pens which indicate that he could write. Maybe he was still a scholar, or writing was a function of his employment? He was a young man at the start of a life cut tragically short.

Folklore and collective memory

The discovery of the young man's remains in the 1960s are very much within living memory. Once he was found, several oral traditions - passed down through the generations - became related to him. Like a tradition told locally of a burial by a distinctive rock called Creag a’ Bhodaich, the rock of the old man. This was recorded by the Rev G Hutchinson in his 'Reminiscences of the Lews' in 1873.

Rev Hutchinson also recorded another tradition of an argument between two young men, a murder and the fate of the murderer. This was related onwards to the local newspaper, the Stornoway Gazette, shortly after the find of the man and his clothing:

Two youths attending the school at Stornoway went to the moors on a birds’ nesting expedition. They quarrelled when sharing out the spoil, and one of them felled the other by a blow on the head with a stone. When he realized that his companion was dead he buried him, and fled to Tarbert, Harris, whence he made his way to the south and took up a seafaring life.

However, it is said, that his past eventually caught up with him:

Many years afterwards his ship put into Stornoway harbour and he went ashore, probably intending to remain incognito. But he was recognized, convicted of murder, and hanged on Gallows Hill

near the castle in Stornoway.

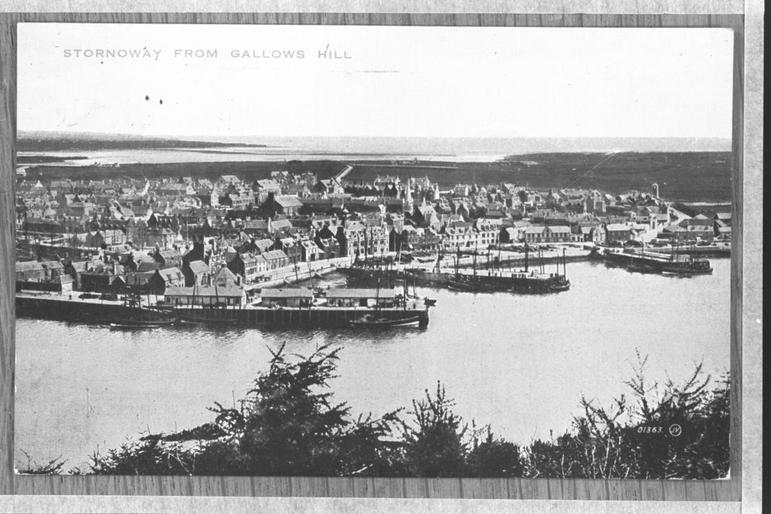

19th century postcard of Stornoway from Gallows Hill.

Supernatural stories

But there are also some supernatural stories associated with the Arnish Moor man and his murderer’s fate. It was said that the murderer was recognised whilst eating in an inn in Stornoway, when the bone handle of his knife began to bleed. There was a folk belief that bones bled when handled by a murderer.

Others told of a ghost that haunted the road close by the turning off to Grimshader, that was not seen again after the man was found.

These traditions perpetuate the memory of the young man and his murderer, and they are well known in and around the area in which the victim was found.

Further stories were generated as a result of the excavation of the man and his possessions.

The family of the people who found the remains still live in the area. Intense local interest in the man and his life remains.

Retelling the story in the local community

The Arnish Moor man's possessions are now display at the Kinloch Historical Society Museum in Balallan, only ten miles from the site of the burial.

Given the very fragile condition of the clothing, it is not possible to put them on display. In its place, National Museums Scotland and the Kinloch Historical Society will work together to create a representation of the clothing.

First we must ask: do you create the replicas as they would have been first made and in perfect condition, or would it be more accurate to create them as they were found and are now, patched, and worn?

Written by

Dr Anna Groundwater

Principal Curator, Renaissance and Early Modern History