Five remarkable prehistoric and early medieval finds from Kilmartin Glen

News Story

Kilmartin Glen in Argyll is one of the most impressive archaeological landscapes in Britain.

From Neolithic rock art to early medieval hillforts, people have people have used the Glen as an arena for ceremony and status over thousands of years. Here we highlight five objects that evoke the story of Kilmartin Glen.

1. A symbolic carved stone, Ri Cruin

Kilmartin Glen has a dense concentration of Late Neolithic Atlantic rock art. This art is often composed of intricate linear and circular designs pecked into rocky outcrops and monumental stones. Other designs are much rarer, though depictions of Early Brone Age metal objects were carved into cist slabs and covered by burial cairns.

One of the most curious is the Ri Cruin ‘halberd pillar’. This narrow vertical slab (or ‘pillar’) stood at the eastern end of a cist, one of three covered by a large cairn. At the opposite end of the cist was a slab decorated with carvings of axeheads. The ‘pillar’ was decorated with a series of overlapping carvings variably considered to be a boat or a hafted halberd (an Early Bronze Age curved blade mounted at a right-angle to a long haft).

The original pillar was destroyed in a fire. However, a cast survives in the National Museums Scotland collections. This allowed fresh study and interpretation by Stuart Needham and Trevor Cowie. The study concluded that this pillar comprised an early, rake-like carving that was later converted into an upright halberd. This may have been done especially for burial and might communicate the importance of the person buried.

The Ri Cruin pillar is the only one of its kind from north-western Europe.

2. A Late Bronze Age offering: the Torran hoard

Around three thousand years ago, people offered up a group of bronze tools and weapons high on a slope, probably in a rock shelter, at Torran, a few kilometres north of Kilmartin Glen. The hoard originally included two spearheads (one now lost), rings, a knife, axeheads, and a socketed gouge.

Many Late Bronze Age hoards are considered to have been abandoned or designated ‘scrap’. But all of the artefacts from Torran were buried complete and functional. Some showed signs of use. One of the axeheads hints at Irish connections; another connects with Yorkshire traditions. Could these really be scrap?

Instead, this appears to be a significant collection of weapons and tools. Perhaps they were prized by the people who used them and offered to the land or to prehistoric deities. Hoards of metalwork were gathered and buried across Europe at this time for many different reasons. The Torran hoard was probably an expression of the wealth and beliefs of those living here.

3. Imported glass

This pale blue shard of translucent glass may not look like much from a distance. Up close, however, its constellation of bubbles and softly undulating surface reveal it as one of the rarest types of early medieval finds in Scotland.

It comes from a delicate form of drinking vessel produced on the Continent in the sixth to eighth centuries AD. It could either be from a palm cup or bell beaker, both of which had rounded ends. In other words, these were cups for feasting, and could not be put down until they were drained!

Finding imported Mediterranean and Continental glass and ceramic from power centres like Dunadd is significant. It provides critical evidence that kings of Scots, Picts, and Britons had long-distance networks in the so-called ‘Dark Ages’. These trade links supplied the elite with luxury goods like wine, spices and rare dyes.

Dunadd has one of the largest assemblages of imported Continental ceramic in Britain. This includes extremely fragile sherds of glass from vessels that came with them. One can imagine the colour of wine as seen through a cup lit by the hearth fire, and with some imagination, get a glimpse into the smells and tastes of an eary medieval royal feast.

Glass vessel fragment from Dunadd hillfort, Argyll. Museum reference X.1996.293.1324.

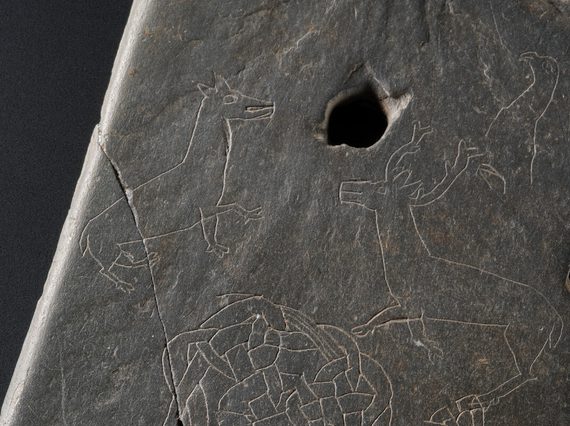

4. A mysterious decorated slate plaque

This intriguing plaque of slate from the early medieval hillfort of Dunadd remains a mystery. The decoration on the front face has both animals and interlaced knotwork. They are of a style that dates to the ninth or tenth centuries, a period when Dunadd was going out of use.

It is a ‘motif piece’ for working out patterns, of a kind with notable parallels from Viking Dublin. It is also notable that this type of slate is not local to Dunadd.

Despite its function as a ‘scratch pad’, the perforation shows that at a certain point it was suspended from a cord. It may have been worn as an amulet. Perhaps the sign of the cross in the interlace knots, or the carvings of animals, were seen as having some protective power.

Among the images and symbols are raptors in flight, deer in motion, and several attempts at a complicated knotwork cross.

5. A bird-headed brooch mould

This is one of a large assemblage of clay moulds found in the early medieval hillfort of Dunadd. This one was used to cast a penannular brooch of 28mm diameter, with decorated hoop and terminals in the shape of bird heads. Penannular brooches were used to fasten cloaks, but were also badges of elite status in the early medieval period. They were produced in hillforts like Dunadd and given as gifts from lords to their clients.

Brooches with bird-headed terminals are rare in Scotland. But they were popular in 7th-century Anglo-Saxon Northumbria. However, this brooch is unique in having an interlace-decorated hoop. This is something seen only in the finest Pictish and Irish brooches of the 8th century.

The workshop finds from Dunadd show examples of creative mixing and melding of art styles in the early medieval period. It is likely that the lords of Scots, Picts, Britons, and Anglo-Saxons who converged here for feasts and assemblies brought their craftspeople with them, exchanging ideas. Even though we only have debris from casting rather than the finished products, it is clear the Dunadd workshops attracted the most talented metalsmiths of the day.