Highland Style: Tartan trends in Georgian Britain

News Story

Highland dress is among the most recognisable symbols of Scotland. It has historical roots in the display culture of medieval Gaelic society.

During the 18th and 19th centuries this living tradition was reinvented to suit the social, cultural, and political landscapes of Georgian Britain. Learn how Highland dress evolved into what we know today.

Originally ceremonial Highland dress was the preserve of clan chiefs and their retainers. It was regarded as a marker of wealth, power, and sophistication within medieval Gaelic society. By the early eighteenth century, improved travel and commercial ties across Scotland had fostered a general preference for Lowland fashions that transcended geographical and cultural boundaries. Despite this, Highland dress costume remained an important aspect of aristocratic display in the Highlands. It spoke to the ingrained warrior traditions of the region.

‘Piper to the Laird of Grant’ by Richard Waitt, 1714. Piper William Cumming belonged to a family of trained musicians who served the Lairds of Grant. Pipers were an important part of the retinue of retainers meant to communicate the status of a clan within a region. Suits of Highland dress acted as livery, worn to signify loyalty, wealth, and a shared sense of kinship.

A controversial Romance

Association between the plaid, weaponry and tartan of the Highlanders with the Jacobite rebel army after the 1745 rising led to its restricted use from 1747. The Act of Proscription which came into force for parts of Scotland in 1747 aimed to stop Highlanders from using the weapons and dress of war which were so deeply associated with their culture. This caused the form, function, and symbolisms of the costume to change irrevocably.

The ban applied only to civilian men and boys, and only restricted the use of particular clothes: plaid, trews, philibeg, and tartan outer coats/cloaks. At the same time, the kilt and plaid were retained for use by Scottish soldiers serving in the British army. This effectively transformed what had been a marginalised regional dress into a glorified symbol of the state. With this successful rehabilitation, the ban on civilian use of Highland dress was eventually lifted in 1782.

Painting, full length portrait of an Officer believed to be of the 81st (Aberdeenshire) Highland Regiment, oil on canvas, artist unknown, c. 1780. Museum reference M.1965.196.

Inspired by the Romantic movement that was popular in Europe, Highland aristocrats, gentlemen, and military officers formed a number of lively clubs and societies across Britain. They contributed to preserving the cultural traditions of the Scottish Highlands.

Members of these clubs re-envisioned Highland dress costume for the modern age, but with an eye towards the past. They looked to the material worlds of previous generations for inspiration, incorporating what they observed in surviving objects, portraiture, and oral tradition.

The subsequent ‘revival’ of Highland dress at the turn of the 19th century was not without controversy. There was disagreement on what constituted an authentic Highland costume and who had the ancestral right to wear it. What one deemed accurate, others saw as a series of embellishments that wilfully burlesqued the character and habits of a region.

Costume plates from A New Geographical Dictionary by John Barrow (1759-60). The Dictionary contained over 140 engravings, including maps, perspective views of places, structures, and ancient ruins, and several plates depicting the traditional costumes of various regions around the world. Although the Dictionary contained detailed maps of Scotland, Ireland, England and Wales, only the regional dress of the Scottish Highlands was described and illustrated in detail. Restricted since the last Jacobite Rising of 1745–46, Highland dress was a subject of popular fascination in Georgian Britain.

It also proved increasingly difficult to ignore the emerging hypocrisy. Highland elites outwardly celebrated the clan society of their forefathers, while also enacting schemes of economic and agricultural improvement on their lands that upturned the lives of their tenants. In this fraught context, the elaborate costumes of members of Highland clubs and societies during the closing decades of the Georgian era came to represent an uneasy meeting of excess and loss, of material fact and historical fiction.

This coat of Royal Stewart tartan was worn by a member of the Highland Society of London in the early 19th century. Following the repeal of the Highland dress ban in 1782, Highland clubs and societies worked to transform the costume into a patriotic symbol of Scotland. They positioned it as a living link to a bygone past, promoting the dress as a national costume. Museum reference H.TTA 15.

From the late 17th to mid-18th century, tartan emerged as a symbol of Jacobite sympathy and anti-Union feeling. This suit of Highland clothes was acquired in Edinburgh by English Jacobite Sir John Hynde Cotton in 1744. Quality tartan costume which pre-dates the last Jacobite Rising of 1745–46 is exceedingly rare, due to the Highland dress ban that followed in its wake. Museum reference K.2003.16.1-3.

The birth of modern Highland dress tailoring

While many aspects of Highland dress culture were viewed as distinctly Scottish, it was not isolated from the wider landscape of European fashion. Despite its characterisation as ancient by those who sought to preserve and promote its use throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, there was much about the Georgian style of Highland dress that was materially modern.

It was a reactive and highly adaptable mode of ceremonial costume. It altered to reflect the cultural preoccupations and sartorial preferences of its wearers. The adaptiveness of Highland dress ensured its survival as a living tradition well beyond the Georgian period, cementing its place within the pantheon of Scotland’s national iconography.

The early 19th century saw an evolution in elite male tailoring. Inspiration came from archaeological discoveries made in Italy and Greece at the close of the 18th century. British tailors began to cut, piece, and manipulate cloth in ways that played with the athletic and statuesque qualities of the human form. In fashionable menswear, inventive shaping techniques were employed to give the illusion of fuller chests, broader shoulders, toned thighs, and slim waists.

Kilt suit belonging to William Blackhall of Blackfaulds, West Lothian, c.1822. Blackhall’s fashionably cut suit of Highland dress is composed of four tailored pieces: a coat and waistcoat of Glenorchy tartan and a box-pleated kilt and fringed shoulder plaid of Cumming tartan. Museum reference A.1993.208 A; A.1993.208 B; A.1993.208 C; A.1993.208 D; A.1993.208 E.

Kilt suit of Mackintosh clan tartan, c.1820. Museum reference H.TTA 20 A.

Woollen fabrics came into favour. Their natural strength and flexibility complemented the vogue for form-fitting garments. The resulting silhouette sought to celebrate a classical ideal of the 'masculine' shape. These changes were recorded in professional tailoring manuals and further refined by the invention of the measuring tape. Now a standard piece of equipment, its introduction in the late Georgian period enabled tailors to take swift and accurate measurements of their clients for the first time.

It was during this era of innovation that a more formulaic approach to Highland dress outfitting began to appear. The voluminous swathes of the belted plaid gave way to the structured little kilt. Even as they worked to modernise it, tailors sought to reference the medieval origins of Highland dress. They emphasised its status as a regional, martial costume.

They achieved this by incorporating fabrics and motifs that spoke to a romanticised vision of clanship. This was famously popularised in the early 19th century by the state visit of George IV to Edinburgh in 1822, as well as the literary cannon of Sir Walter Scott.

Certain features of cut, construction, and accessorising became accepted practice within a relatively short period of time. Family tartans, heraldic buttons and badges, and military embellishments such as bullion ribbon and braiding took centre stage. These elements still lie at the core of how Highland dress is imagined and marketed today.

Image gallery

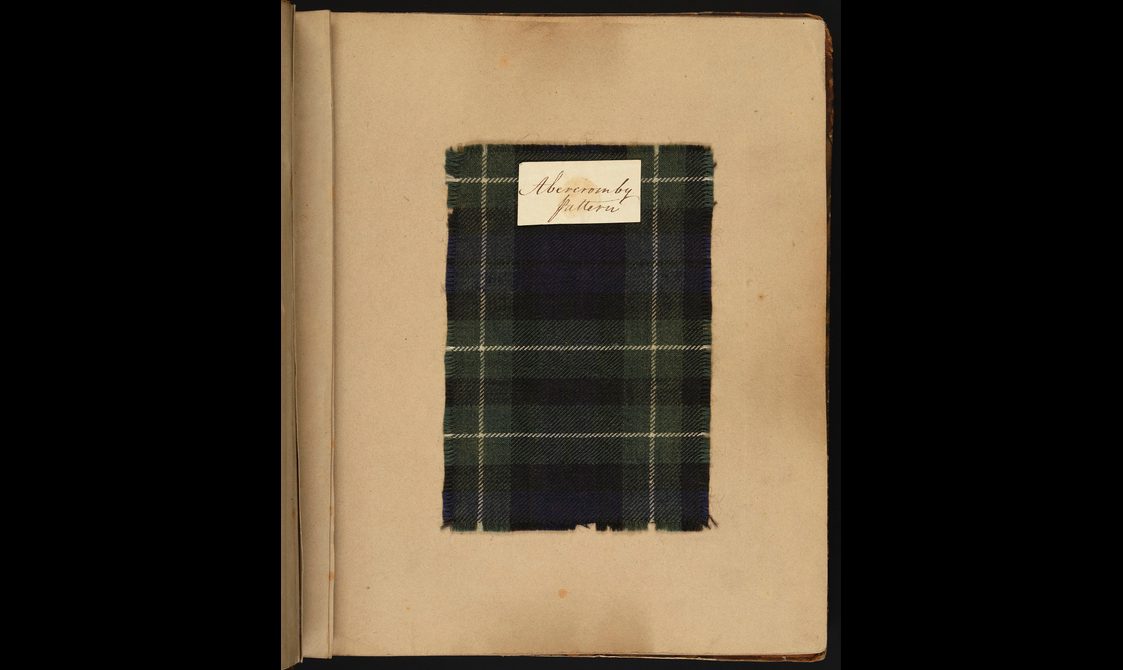

A sample of ‘Abercromby’ tartan, c.1822. Collected by the English antiquarian Sir Samuel Rush Meyrick, it is a commemorative tartan created in honour of General Sir Ralph Abercromby. Museum reference H.TTB 8.

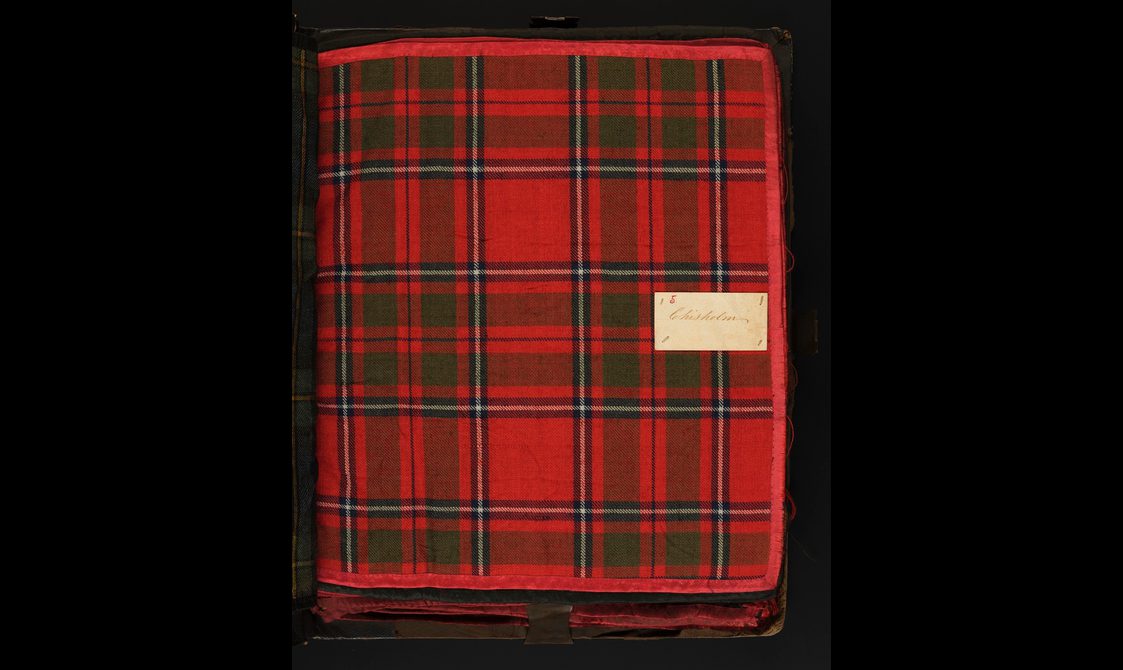

A sample of Chisholm clan tartan, from a bound collection of 58 clan setts dating from the early 19th century. Each sample in the volume is edged with silk and meticulously labelled, suggesting it once belonged to a textile merchant or manufacturer. Museum reference H.TTB 11.

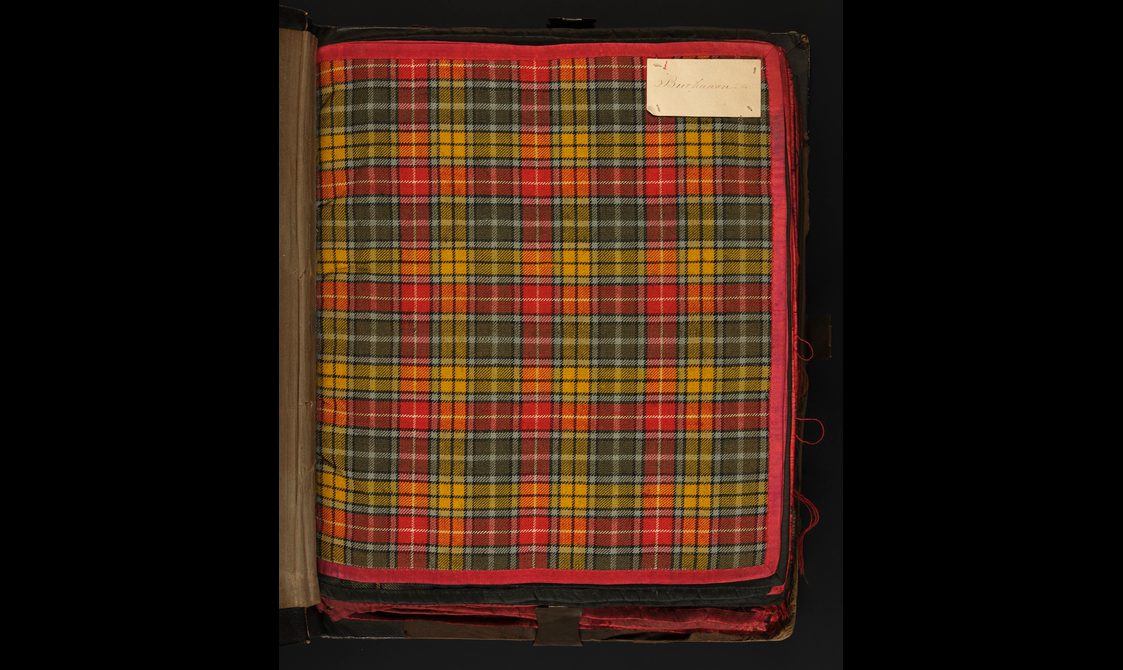

A sample of Buchanan clan tartan, from a bound collection of 58 clan setts dating from the early 19th century. Each sample in the volume is edged with silk and meticulously labelled, suggesting it once belonged to a textile merchant or manufacturer. Museum reference H.TTB 11.

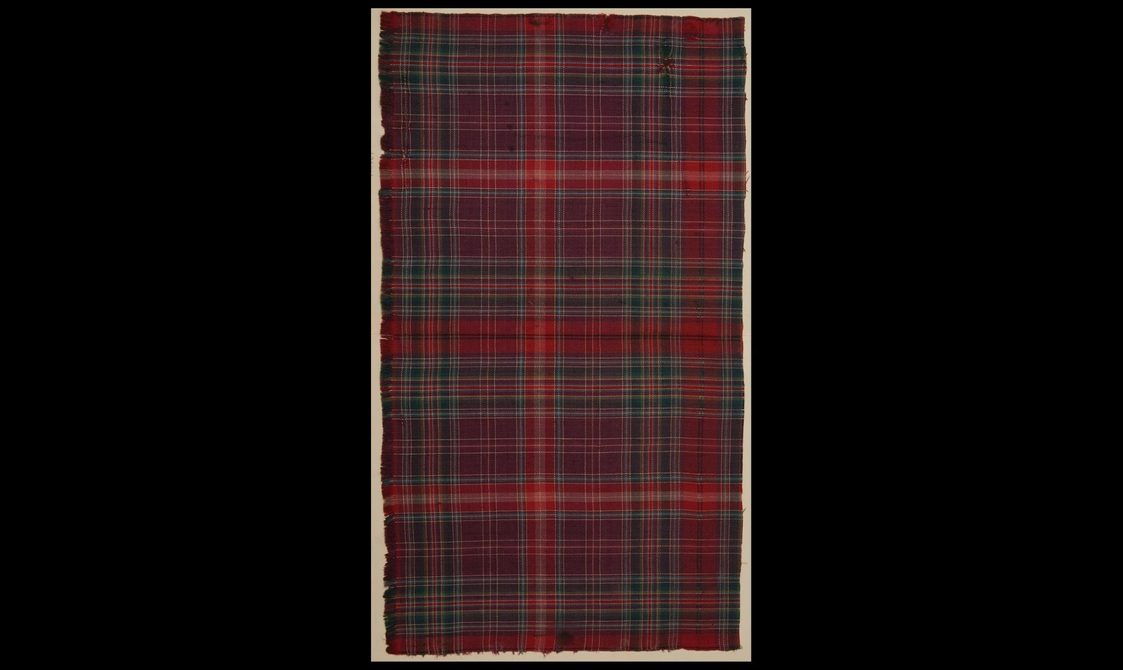

A piece of ‘fancy’ tartan, c.1790. The pattern uses 8 solid colours to create a busy cloth of 36 interweaving shades. Museum reference H.TTC 1.1.

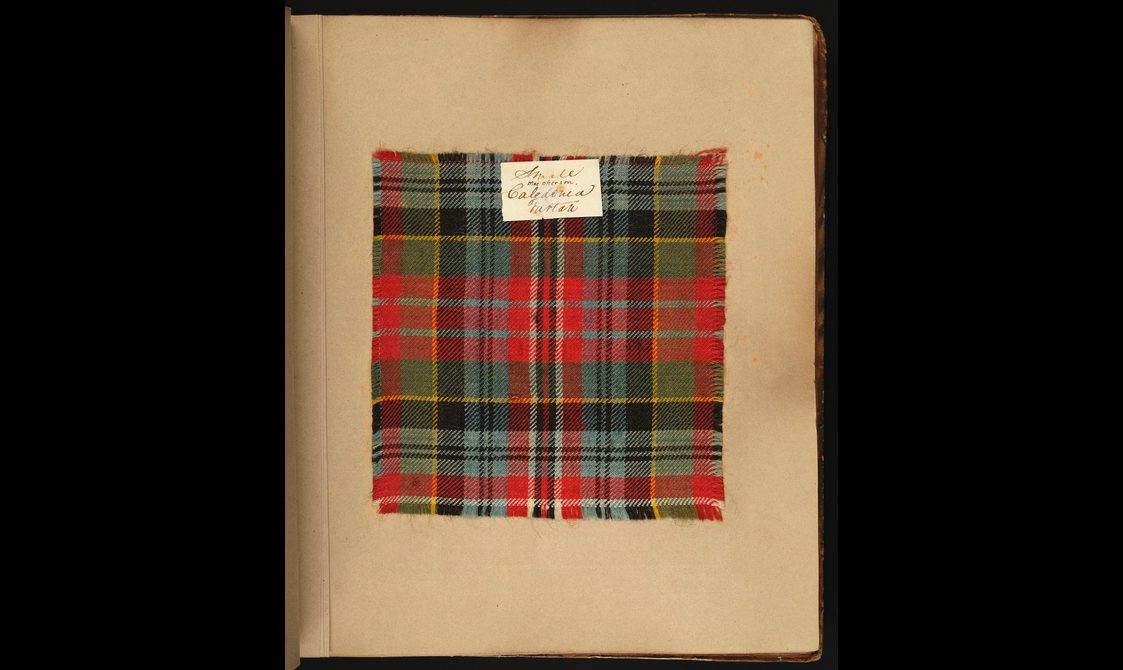

A sample of ‘Caledonia’ tartan, c.1822. Collected by the English antiquarian Sir Samuel Rush Meyrick, this patriotic pattern was claimed as the Macpherson clan tartan by the Chief, Duncan Macpherson of Cluny in 1816. Museum reference H.TTB 8.

Tartan as fashion

Beyond Highland dress tailoring, Scottish tartan emerged as a popular fashion fabric in Georgian Britain. The cloth found its way into a variety of everyday and occasional garments, such as women’s cloaks, gowns, and children’s clothing. Initially regarded as the distinctive cloth of the Highlands, by the end of the 18th century it had garnered a reputation as a desirable Scottish product characterised by its multicoloured elegance.

A heavily embellished silk tartan gown worn by Sarah Justina Davidson of Tulloch. This outfit was part of her wedding trousseau and dates from her marriage to Ewen Macpherson of Cluny in 1832. The silk thread embroidery that adorns both the skirt and the belt is a reference to red whortleberry, a clan plant badge with significance to both the Davidsons and the Macphersons. Museum reference A.1934.387.

A little boy’s Highland-style kilt dress made from Prince Charles Edward tartan and decorated with military braiding, c.1815-20. The cut and construction of this garment incorporates many of the features found in the revival style of adult Highland dress costume, but with an eye towards the practical concerns of child-rearing in the early 19th century. Museum reference A.1994.1334.

As tartan grew in desirability, weavers took inspiration from the ritualised heraldry practiced by Highlanders in the past to fashion an array of setts assigned to specific clans. With a controversial history now more than 200 years in the making, the extent to which clan tartans can be considered a valid avenue of personal, familial, and national expression remains a source of controversy among contemporary Scots.