Inventors of photography: Exploring Victorian photographic techniques

News Story

Discover how Victorian inventors and entrepreneurs succeeded in capturing the very first images.

What is a daguerreotype?

Nowadays we often refer to any old-looking, sepia-tinted photograph as a ‘daguerreotype’. But the word daguerreotype in fact refers to a specific photographic process. It was invented by the flamboyant Parisian inventor and entrepreneur Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre (1787-1851).

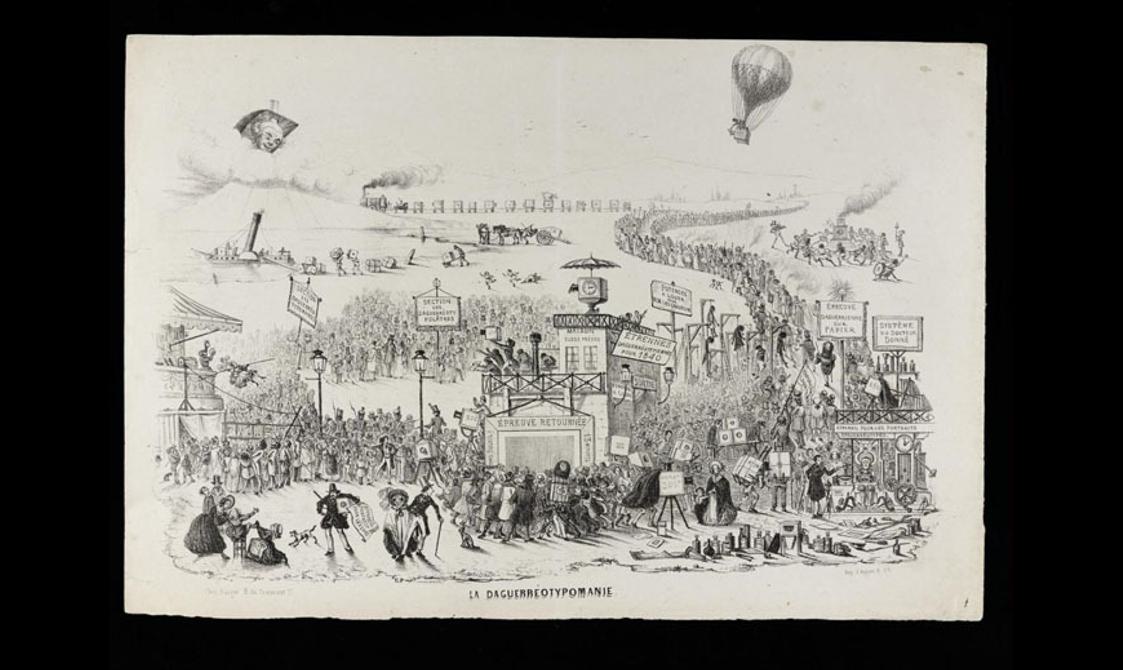

Daguerre was the first person to publicly announce a successful method of capturing images. His invention was an immediate hit, and France was soon gripped by ‘daguerreotypomania’. Daguerre released his formula and anyone was free to use it without paying a licence fee. Everywhere except in Britain, where he had secured a patent.

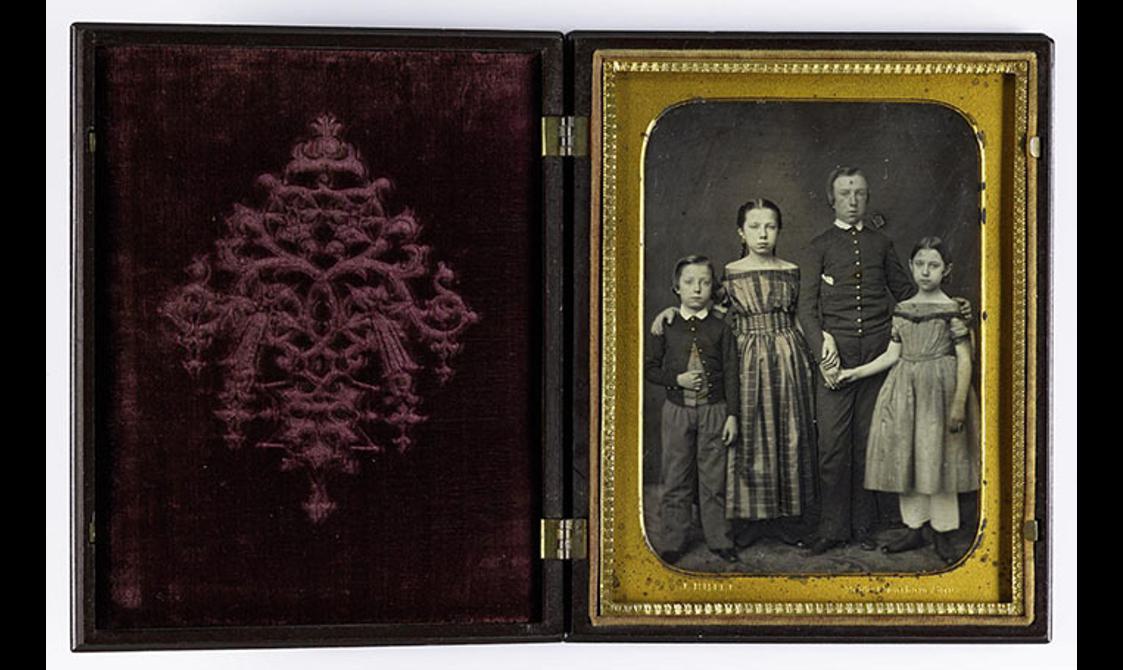

A daguerreotype is a single reversed image, made as a direct positive onto a silvered copper plate. Its reflective surface is an easy way to tell the difference between a daguerreotype and an early photograph taken using a different technique. The image is made of a combination of silver and mercury, resting on that plate. It is extremely vulnerable to damage, and can easily be brushed off, even after being ‘fixed’. Because they were so fragile, they were usually protected with a cover-glass and held in small leather-bound cases as treasured objects. In this way they were similar to miniature painted portraits.

The film clip below shows the reflective surface of a daguerreotype.

The daguerreotype process only creates one image at a time. Multiple copies of the same picture could only be produced by taking several photographs, or by engraving directly from the daguerreotype plate.

Image gallery

Daguerreotype of two boys and two girls, by Julius Brill of New York, 1852-60. From the Howarth-Loomes Collection at National Museums Scotland. Museum reference T.2023.44.2.135.

Daguerreotype camera designed by Marc Antoine Gaudin (1804‑1880) of Paris in 1841 and made commercially by the instrument‑maker NMP Lerebours (1801‑1873).

Black and white lithograph entitled La Daguerreotypomanie. From the Howarth-Loomes Collection at National Museums Scotland. Museum reference T.2023.44.8.90.

What other processes were invented?

Daguerre was not the only person experimenting with photographic techniques in the early 19th century. Across the channel, English landowner, scholar, and scientist William Henry Fox Talbot (1800-77) had produced his first successful negative, in the summer of 1835.

After further work, he discovered the possibility of developing an invisible latent image. This meant shorter exposure time. He patented his improved process in February 1841 which was known as the calotype. It is the ancestor of nearly all photographic methods using chemistry. Digital photography wouldn't emerge until the late 1990s.

Carte-de-visite of seated William Henry Fox Talbot holding the lens of a camera, by John Moffat, Edinburgh, 1864. Museum reference T.1937.93.

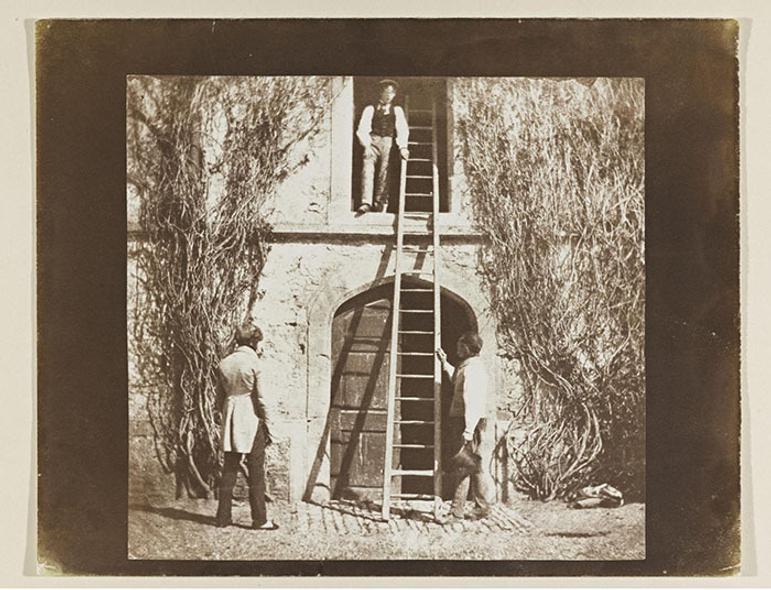

The calotype negative was made by projecting an image through a lens on to a piece of chemically sensitized paper fixed inside the camera. Here it formed a latent image on the paper, unseen by human eye. When developed, this produced a negative image. In turn, this negative was placed in the printing frame with a second piece of sensitized paper beneath it and exposed to sunlight. This produced a positive image, which had to be fixed with chemicals.

Calotype images are not as pin-sharp as daguerreotypes. But they had one great advantage: more than one image could be produced from a single negative. Yet both processes were cumbersome and very expensive. What was needed was a faster, cheaper method to really fuel the fire of Victorian photomania.

The Ladder, Plate XIV from Talbot’s Pencil of Nature, the first book to be illustrated with photographs. Salt print from a calotype negative. Museum reference T.1937.92.14.

Early calotype camera with lens dating from c. 1840, used by Talbot. Museum reference T.1936.21.

How did photography become cheaper?

And so we come to 1851, when London-based sculptor Frederick Scott Archer (1813-57) announced his new form of photography; the wet collodion process. This combined the best of Daguerre and Talbot’s methods. But it was easier and cheaper than either, enabling it to become a commercially viable method. The public loved it, and Archer’s process became the foundation of photography for the next 140 years.

A glass plate is coated with the wet collodion solution containing light-sensitive silver salts and exposed whilst the plate is still wet. Photographs have to be taken within 15 minutes of coating the plate so a portable dark room is needed. However, the exposure time is less than for daguerreotypes and calotypes. This made outdoor photography easier. A sharp glass negative image is created that captures microscopic detail. Positive copies can be made from this, usually of albumen prints on paper. These prints are sharper than those created by Talbot’s calotype process and less liable to fade.

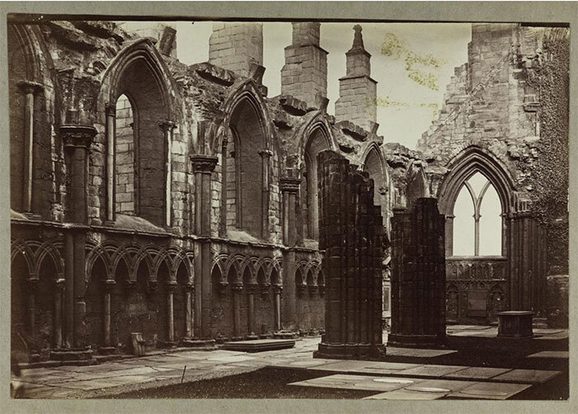

Wet collodion glass plate negative print of ruined abbey. Photographer and date unknown.

Wet albumen print of ruined abbey. Photographer and date unknown.

How was Archer’s method used?

Photographers and manufacturers continued to experiment. They created new ways of using Talbot and Archer’s techniques.

Ambrotypes (or wet collodion positives) were formed by painting the back of the glass negative image with black paint, or placing a piece of black card there. The negative could be placed into a protective case. This resembled that of the daguerreotype, with which it is sometimes confused. The ambrotype, however, lacks the mirror-like surface of the daguerreotype.

In this example of an ambrotype (wet collodion positive), half of the black backing has been removed to demonstrate the effect of a dark background under the bleached negative. From the Howarth-Loomes Collection at National Museums Scotland. Museum reference T.2023.44.1.13.

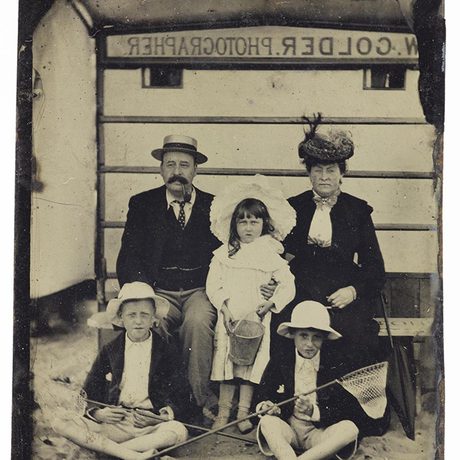

The tintype, or ferrotype, process was a cheaper development of the wet collodion method. It produced a single, positive image on a tinned or enamelled iron support. Often these were embellished with colour, sometimes to the extent that the image no longer looked like a photograph.

Despite the poor quality of the many of the images that resulted from using this process, tintypes enjoyed a long run of popularity. They were still being produced well into the twentieth century, especially by beach photographers. The finished photograph could be handed to the customer within minutes. Prices were seldom above 6d (about £2 today).

Image gallery

Stereo-mania

Also in 1851, the scientist Sir David Brewster (1781-1868) presented lenticular stereoscopy to the world for the first time at the Great Exhibition in the Crystal Palace, Hyde Park, London.

The word stereoscopy derives from the Greek stereos, meaning ‘firm’ or ‘solid’, and skopeō, meaning ‘to look’ or ‘to see’. Any stereoscopic image is called a stereogram.

Originally, ‘stereogram’ referred to a pair of stereo images which could be viewed using a stereoscope. Most stereoscopic methods present two slightly differing images separately to the left and right eye of the viewer. These two-dimensional images are then re-combined by the brain to give the viewer the perception of 3-D depth.

Both stereo-viewers and images were an instant success with visitors. They were enchanted by the new three-dimensional effect.

David Brewster’s lenticular stereoscope was developed by a number of manufacturers hoping to benefit from the huge demand for the images. Hundreds of thousands of stereoscopic images were sold in a major craze which reached every middle-class Victorian drawing-room. Special cameras were developed to make the images, and a variety of viewers produced to keep up with demand. Portraits, scenery, comedic scenes and images of far flung places were all particularly popular.

Image gallery

Hand-held stereoscope on a stand, American, c.1900. From the Howarth-Loomes Collection at National Museums Scotland. Museum reference T.2023.44.10.31.

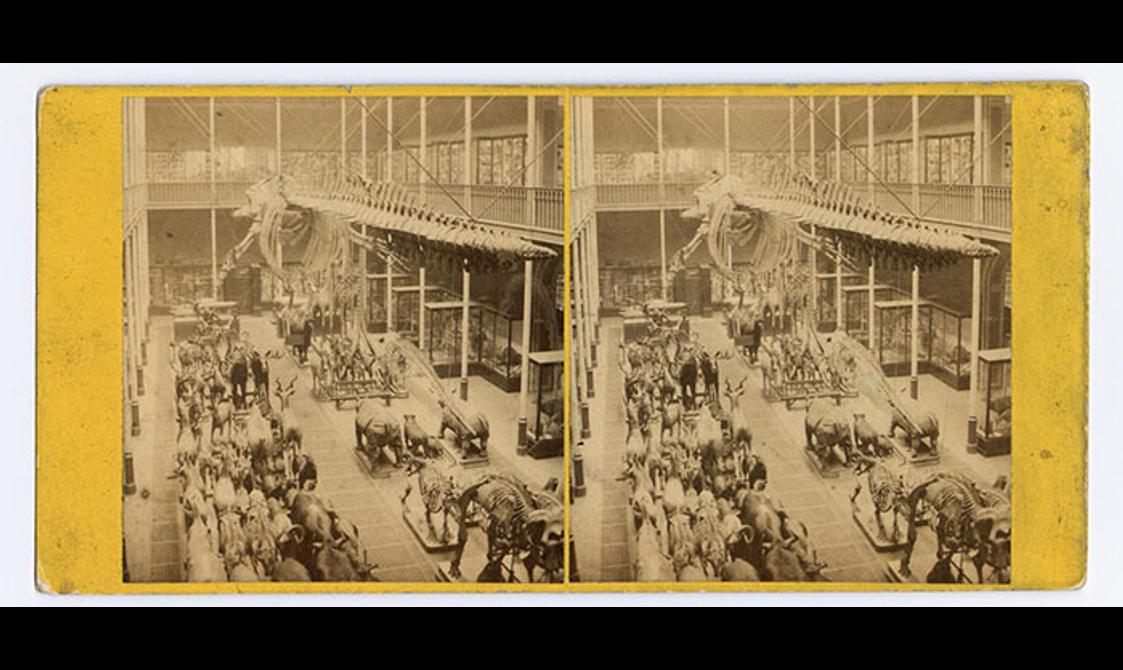

Stereocard of the Art and Science Museum, Edinburgh (now the National Museum of Scotland) by H Gordon of Aberdeen. The image shows a ground floor gallery and a balcony of natural history specimens, both taxidermy and skeletal. Museum reference D.2015.4.

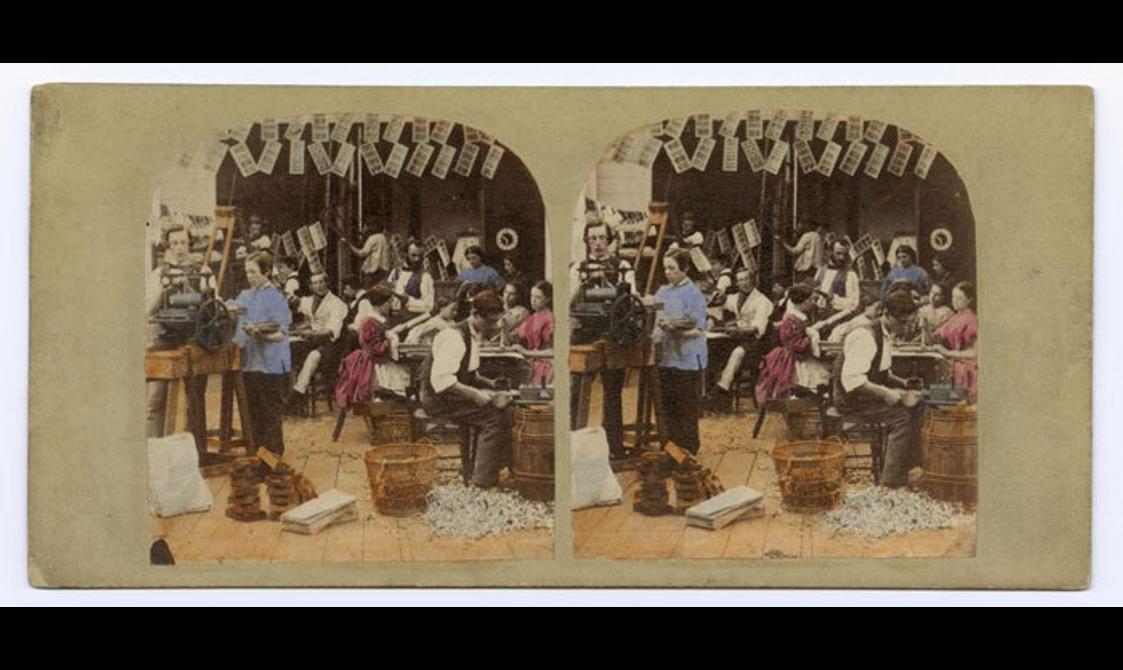

Stereocard entitled 'The Making of Stereographs', by an unknown photographer, 1860. From the Howarth-Loomes Collection at National Museums Scotland. Museum reference T.2023.44.6.16.401.

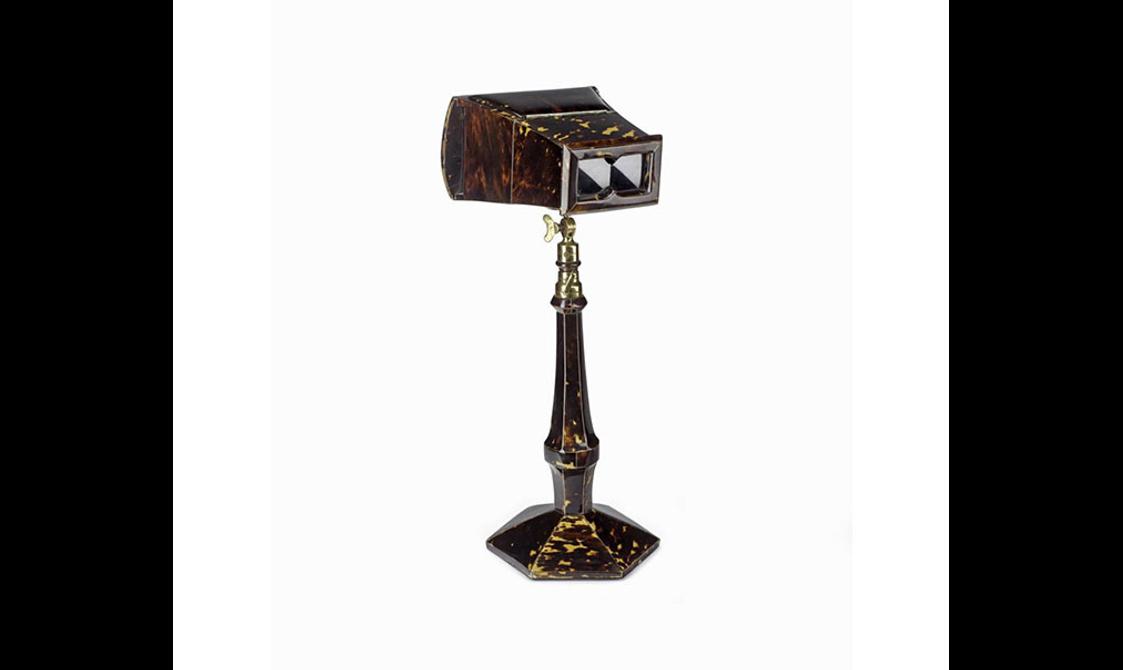

Brewster stereoscope on a tortoise-shell stand, made c. 1860. From the Howarth-Loomes Collection at National Museums Scotland. Museum reference T.2023.44.10.249.

The cartes-de-visite craze

Aspiring Parisian photographer André Adolphe Eugène Disdéri (1819-89) single-handedly created a brand new craze. He realised that he could reduce his costs by taking several smaller negatives on a single plate, this led to the carte-de-visite.

The carte-de-visite was undoubtedly the most popular form of 19th-century photography. It was the Victorian era’s answer to the ‘selfie’. Carte-de-visite fever reached England in about 1857. Unlike earlier forms of photography, it reached almost every level of society.

Carte-de-visite of Her Majesty the Queen, by Cundall, Downes & Co, London, printed on the back: Photographed from life by C Clifford of Madrid, November 14 1861. This was probably the first image of the Queen taken for public distribution. She wrote in her Journal, that for it she 'dressed in evening dress, with diadem and jewels'. From the Howarth-Loomes Collection at National Museums Scotland. Museum reference T.2023.44.4.666.

The Kodak moment

In 1888, George Eastman of the Eastman Dry Plate & Film Company of Rochester, New York, launched a new camera that further widened the market for popular photography. His product was called the Kodak. Eastman wanted something short, pronounceable and unmistakable in a number of languages.

The Kodak camera cost $25 (about £420 today). It came factory-loaded with a sensitised roll-film, enough for one hundred circular images. After these had been exposed, the entire camera was returned to the factory. Here the roll was removed and developed, and the camera was re-loaded with a new roll of film, all for $10 (about £165 today). Eastman advertised this with the successful slogan, "You press the button, we do the rest".

The Kodak camera revolutionised the photographic market. Its simplicity of use and freedom from the mess of darkroom chemistry marked the beginning of photography as a tool and hobby for everyone.

Box Brownie roll-film camera, made by Eastman Kodak Company, New York, c.1900. This is the first in the series of Eastman Kodak’s Brownie cameras. Made of leatherette-covered cardboard and selling for a dollar, it popularised low-cost photography and over 250,000 were sold. Museum reference T.1961.16

The digital revolution

In 1981 Sony revealed the Sony Mavica, the first digital electronic still camera. Decades later, around half the world’s adult population carries a camera in their pocket in the form of their mobile phone.

Photography is more of a sensation than ever. It’s estimated that every two minutes, we take as many photos as were taken during the whole 19th century. What would Daguerre and Talbot have made of that?