Jacobites and tartan: Symbolism and style

News Story

Tartan has long been one of the most recognisable symbols of Scotland. The cultural significances of tartan are often reflections of and responses to the social context in which it was produced and worn. The 18th century tartan garments explored below held symbolic values in respect to the social and political upheavals of the Jacobite risings.

During the early 18th century, tartan cloth and clothing was associated with Scots, and warrior Highlanders in particular. When Charles Edward Stuart, popularly known as ‘Bonnie Prince Charlie’ arrived in Scotland in 1745 to attempt to reclaim his father's throne, he wore tartan at the head of his army. The cloth became an emblem for the Jacobites.

'I am come home'

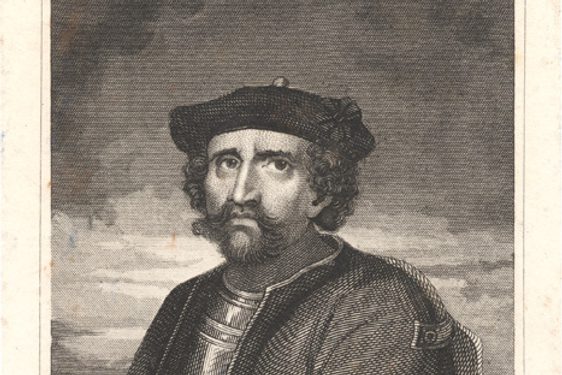

Charles Edward Stuart was born in Rome on 31 December 1720. He was the grandson of the deposed Catholic King James VII and II, who had fled to France from the Protestant William of Orange's invading army in 1688.

He came to Britain in 1745 as Prince Regent, to claim the three kingdoms for his father James VIII and III. In July 1745, Charles set sail from France and landed on the Isle of Eriskay in the Outer Hebrides. He raised his father’s Royal Standard at Glenfinnan on 19 August 1745 and gathered an army of several hundred men, mostly Highlanders.

This challenge to restore the Stuart dynasty has become known as ‘The Fourty-Five’. Personable and energetic, the prince became the focus of the Jacobite cause. To the British government and its supporters, however, he was the ‘Young Pretender’, a rebel usurper. George II and his government posted a £30,000 reward for Charles’ capture.

This elegant tartan frock coat was in the possession of a Jacobite-supporting family for many years. The family had direct links with the prince, and family provenance says it was understood to have worn by Charles during his time in Scotland. Recent examination suggests however that the cloth is early 19th century. Tartan was an important part of an image cultivate by Charles during his life, and since.

Short tartan frock coat with velvet collar and cuffs and lined in wool twill and linen, c.19th century K.2002.1031.

A symbol of opposition

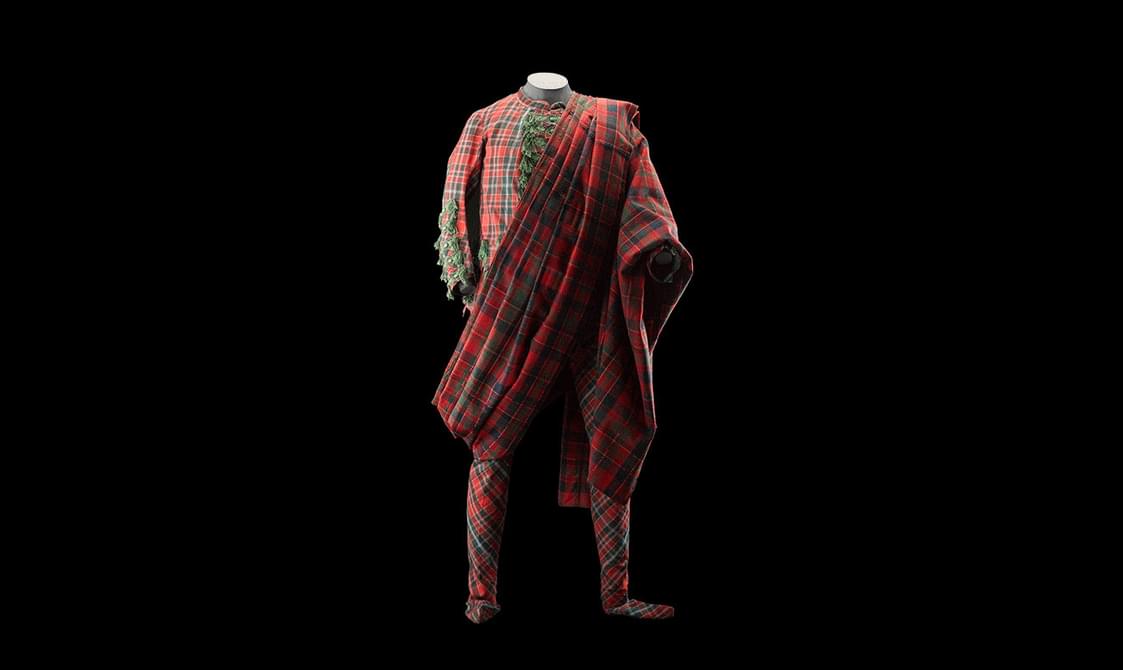

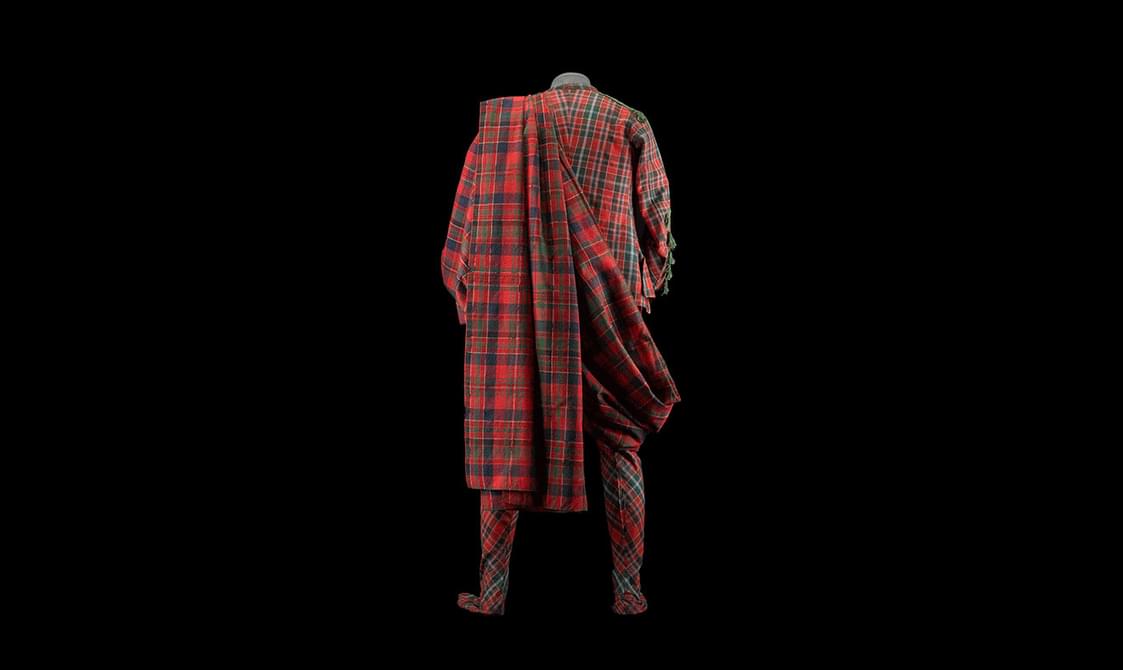

The suit below is a rare and special example of a non-military tartan dating to the mid-eighteenth century.

The suit once belonged to Sir John Hynde Cotton (1686 – 1752). Sir John was an English Tory MP and a Jacobite. He had been a constant opponent of the Prime Minister, Sir Robert Walpole, whose son, Horace Walpole, noted that Cotton ‘had wit, and the faithful attendant of wit, ill nature’. He became a government minister briefly in 1744, but was also communicating with the exiled Stuart court.

Image gallery

Sir John came to Edinburgh in July 1744, which is probably when he acquired this vibrant tartan ensemble. The suit consists of trews (trousers), a jacket, and plaid (a length of cloth wrapped around the body). The finely woven cloth uses mainly red and green to make five different patterns of tartan.

Cotton may have commissioned the outfit himself, with the specific intention of identifying himself with the Jacobite cause, or it may have been a gift. Either way, it had to be enlarged before it would fit. Sir John Hynde Cotton was a large man, standing at an imposing 6 feet 4 inches tall. The writer William Cole described him as 'one of the tallest, biggest, fattest men I have ever seen'.

An impressive uniform

The tartan uniform below was probably owned by Stuart Threipland of Fingask. These garments were worn by members of the Royal Company of Archers. The Company was originally established in 1676 to promote the sport of archery in Edinburgh. It was revitalised in 1713 and a new, all-tartan uniform created. Tartan was fashionable at the time as an expression of anti-Union and pro-Jacobite sentiment, and many of the company were known Jacobites, including the Threipland family.

Today, the Royal Company of Archers forms the King’s Bodyguard in Scotland. Duties include attendance at the annual Royal Garden Party at the Palace of Holyroodhouse and at investitures. The Company also still operates as an archery club.

Fashioning support

Women too used clothing to demonstrate their allegiance to the Stuarts. In 1746, a group of ladies in Edinburgh planned to celebrate Charles Edward Stuart’s birthday wearing tartan dresses and white ribbons. At news of this, authorities were concerned at this show of support for the Jacobite prince.

Silk gown embroidered with flowers, said to have been worn by Margaret Oliphant of Gask, c.1745. Museum reference A.1964.553.

This beautiful silk gown (museum reference A.1964.553) was reportedly worn by Margaret Oliphant of Gask, a firm Jacobite, when she was received at the Palace of Holyrood House in 1745. While the dress was most likely adapted for the occasion, rather than made for it, the embroidered white roses in the design may have taken on a new significance as they were another emblem of loyalty to the exiled Stuarts.

A tartan ban for some

After Charles Edward’s final defeat at Culloden in 1746, new laws were introduced to the Highlands with the aim of disarming the population and crushing future chances of rebellion. In addition to making it illegal to carry and own ‘warlike weapons’, the 1747 Act of Proscription banned civilian men in Scotland from wearing ‘Highland Clothes’ and from using Tartan for coats. The government saw the power of dress to unite Jacobites, and Highlanders in particular, and banned it in an effort to restrict its rebellious use.

“no man or boy, within that part of Great Briton called Scotland, other than shall be employed as officers and soldiers in his Majesty's forces, shall on any pretence whatsoever, wear or put on the clothes commonly called Highland Clothes (that is to say) the plaid, philibeg, or little kilt, trowse, shoulder belts, or any part whatsoever of what peculiarly belongs to the highland garb; and that no tartan, or partly-coloured plaid or stuff shall be used for great coats, or for upper coats”

It is important to note that this applied only to civilian men and boys. Women, and soldiers of the British army were exempt. While Highland dress and tartan had become a symbol of Jacobitism, it also held meaning as the ancient dress of the warrior, and Highland elite – which is why it was used by Charles Edward Stuart in the first place. Scottish military regiments continued to use this dress and some of their commanders even had their portraits painted in it.

By the later 18th century, tartan was firmly identified with Scottish participation in the British military and colonial exploits, but retained its long and layered history. The Act was repealed in 1782.

Uniform of the Royal Company of Archers is on display in the Scotland Transformed gallery at the National Museum of Scotland.