Romans in Scotland: Major archaeological sites

News Story

Archaeological finds from Rome's invasions of Scotland can be found throughout the country, from the Solway Firth to Shetland. The most prominent sites, however, are in southern Scotland, including Trimontium, the Antonine Wall and Traprain Law.

Trimontium

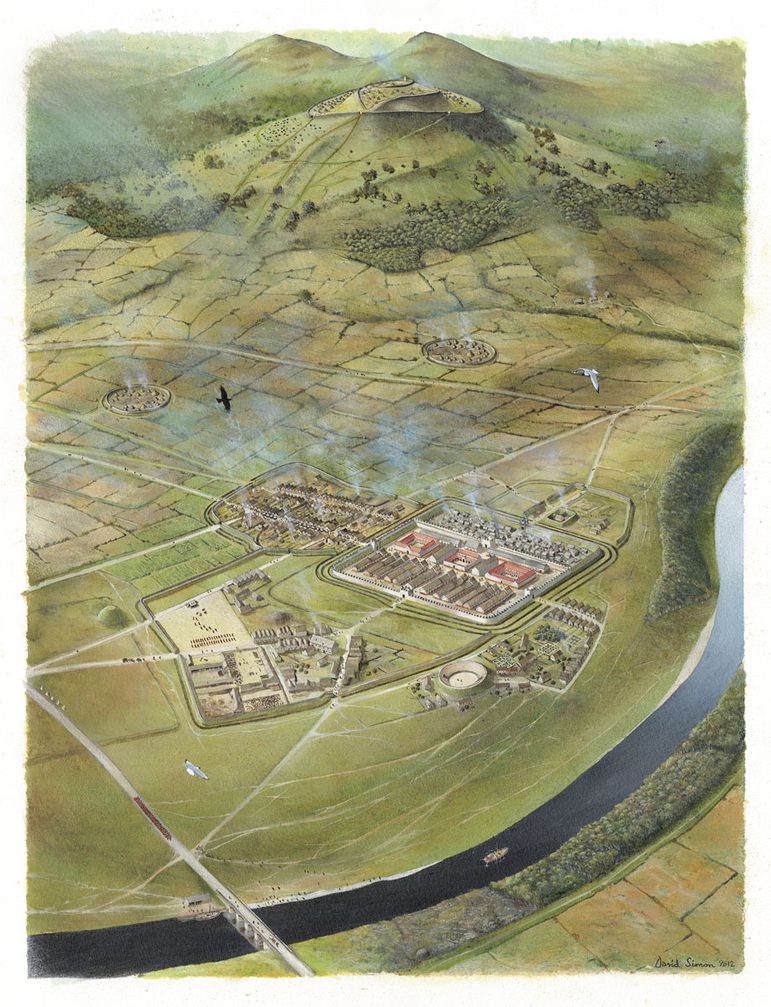

Trimontium was a major Roman fort at Newstead, near Melrose in the Borders. Its Roman name comes from the three hills of the Eildons, the dominant landmark in the area. The site was well-chosen: it sits on the river Tweed at a key crossroads where the main road north from York crossed an east-west road running from coast to coast.

As the Roman occupation of Scotland varied, so did Trimontium’s role. At times it was a frontline defence for the Empire, at others a major supply base behind the shifting frontier. It was home to a powerful garrison of at least 500 cavalry, perfectly suited for the rolling Borders terrain. On occasion a detachment of legionaries provided a back-up of heavy infantry.

Trimontium was more than just a fort. Defended annexes protected a civilian community which had travelled with the troops. The families lived here along with traders and craftworkers, for this was also an industrial complex. Furnaces and kilns smoked as iron was smithed, pots were fired and glass jewellery was made. Overall, more than a thousand people would have called Trimontium home.

After the Romans left, the massive ramparts and ditches were levelled by generations of ploughing, but casual finds gave clues to its location. From 1905-1910 James Curle, a Melrose solicitor, led excavations to rediscover the fort. This revealed its history and recovered an exceptional range of finds from pits dotted around the site. These had once been wells. When they were abandoned, material was deposited in them. The waterlogged conditions preserved organic remains such as leather, textiles and wood, which would normally rot away, and kept iron tools so fresh that they could still be used today.

Artist's depiction of the Roman fort at Trimontium near Melrose in the Scottish Borders.

Today, these discoveries form the core of the Roman displays in the National Museum of Scotland, and a display about the site at the Trimontium Museum in Melrose.

The Antonine Wall

Hadrian’s Wall is not the only Roman frontier in Britain! Shortly after Hadrian died in AD 138, his successor Antoninus Pius decided to abandon his predecessor’s frontier and reoccupy southern Scotland. This served two purposes – a military victory would help to secure his position as emperor, and solve continuing trouble on this restless northern frontier.

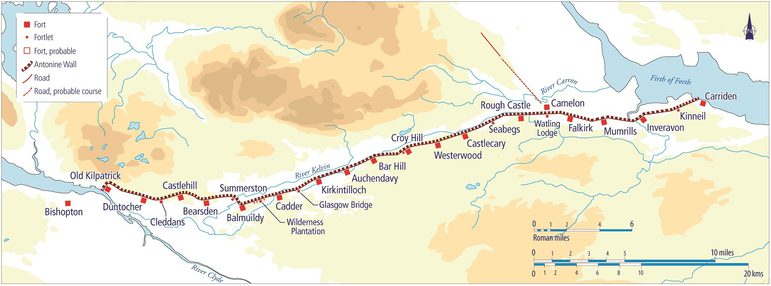

Map of the Antonine Wall in the mid-2nd century AD, showing the locations of forts at regular intervals along it.

The army re-occupied southern and central Scotland, and built a wall of earth and turf across the narrowest part of the country from the Firth of Forth to the Firth of Clyde. This acted as a barrier to prevent raiding and control movement. Today we call this the Antonine Wall.

Defensive pits known to the Romans as lilia at Rough Castle, Falkirk

At the major fort of Camelon, immediately north of the wall, Roman Scotland runs right up against the modern world.

The Wall was built by troops from the three legions stationed in Britain, the 2nd Augusta (based at Caerleon in South Wales), 6th Victrix (from York), and 20th Valeria Victrix (from Chester). It was hard work, with a massive ditch up to 12m wide and 3.5m deep in front of a Wall some 3m high. They also built a road to the rear of the Wall, to make communication easier.

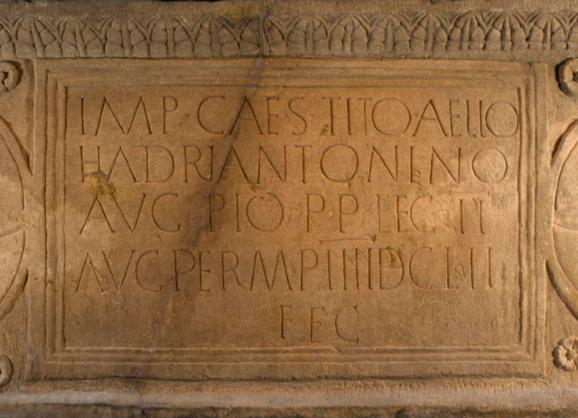

To commemorate their efforts, the legionaries erected sculptures at the ends of the sections they built, recording every hard-earned pace of the construction. At the ends of the Wall, more spectacular slabs were erected. At the west end, on the Clyde at Old Kilpatrick, the goddess Victory is shown in the pose of a river goddess. At the east end, at Bridgeness, a monumental slab carried a large inscription flanked by panels showing events from the army’s work.

The Wall was manned by troops based in forts along its length, with further well-defended forts to the north as far as Perth. Behind the Wall was a network of supporting garrisons, holding down the freshly-conquered areas.

National Museums Scotland holds major collections from forts in the eastern half of the Wall – Croy Hill, Castlecary, Rough Castle, and Mumrills, as well as Camelon, a major strongpoint just north of the Wall. These shine a light on life for this army of occupation. A rich set of inscriptions tells us where the units were originally raised: Nervians and Tungrians from Belgium, Vardullians from northern Spain, Thracians from Bulgaria, and Hamians from Syria, along with legionaries from Italy and Austria.

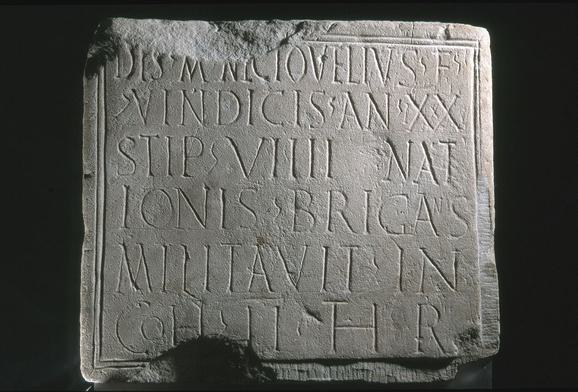

Not all the soldiers hailed from beyond Britannia, however, as units would recruit locally. This was the case with Nectovelius, a trooper buried at Mumrills. His tombstone tells us he served in a unit of Thracians but was himself a Brigantian from northern England.

The grand inscription, in abbreviated Latin, dedicates the slab to the emperor Antoninus Pius, and commemorates the building of 4.652 paces of wall by the 2nd Legion Augusta. Museum reference X.FV 27.

The tombstone of Nectovelius, a soldier in the 2nd Cohort of Thracians, found at Mumrills. The script reads, "To the spirits of the departed. Nectovelius, son of Vindex, aged 29 of 9 years' service, from the tribe of the Brigantes, served in the Second Cohort of Thracians." Museum reference X.FV 16.

Traprain Law

The fertile coastal plain of East Lothian is dominated by the great volcanic outcrop of Traprain Law. This massive hill has drawn the attention of people for thousands of years. It also attracted the attention of archaeologists. Excavations from 1914-1923 by Alexander Curle and James Cree revealed a long history and a wealth of finds, supplemented by subsequent, smaller-scale work.

Traprain Law's distinctive whaleback shape, visible from many miles around, rises up from the fertile fields of East Lothian near East Linton.

The use of this focal hill varied. A scatter of finds shows there was activity in the Neolithic (4000-2500 BC), but its character is unclear. Traprain Law was a place of ritual in the earlier Bronze Age (2500-1600 BC), when it was marked with rock-carvings and used for burials.

This hallowed hill saw a major change in use in the later Bronze Age (1200-800 BC), when it was turned into a substantial defended settlement. Finds show it was a centre of craft and wide-ranging contacts. This was the power-centre of the area.

During the Iron Age (800-1 BC), these power structures broke down, and people moved to smaller-scale hillforts in the surrounding area. Traprain Law remained important as a central place for these groups where festivals and ceremonies would take place.

When the Romans came into southern Scotland, they found people living on the Law once more. Competition had developed among the small-scale communities of the Iron Age, and some groups had grown dominant. It seems they took over Traprain Law as their settlement, and decided to make deals with Rome.

Four late Bronze Age bronze axe-heads found in 2004 on the southern edge of Traprain Law.

Part of the Traprain Law treasure, the largest hacked-silver hoard found either inside or outside the Roman Empire.

The Romans saw these local leaders as a friendly power. There is no Roman military site in the vicinity, and Traprain Law is rich in Roman finds - the bounty from these positive relations with Rome. The people on Traprain chose Roman objects which they could use to show off their privileged status, such as ornate brooches and a rich range of fine glass and pottery vessels.

When the Romans left Scotland and pulled back to Hadrian’s Wall in the late second century, they kept their links with the people on Traprain, who were their eyes and ears in the north. They acted as a buffer between the Roman world and the increasingly hostile northern tribes. This privileged status is seen most spectacularly in the Traprain Treasure, a great hoard of Roman silver which represents gifts and payments from the Roman world for a hundred years or more.

It’s not clear why Traprain fell from use. Activity continued until AD 500 or a little later, but the site then falls silent apart from the realms of mythology, which link it to the legend of St Mungo. His mother, Thenew, was supposedly thrown from the hill by her irate father, King Loth, when she became pregnant. Loth is a fictional figure, but the link to Traprain suggests that the site’s former power still echoed in later centuries.