An unsolved mystery: The coffins found on Arthur's Seat

News Story

Satanic spell, superstitious charm or echo of Edinburgh’s grisly underworld history? We examine the strange tale of these tiny coffins, discovered on Arthur’s Seat almost 200 years ago.

A baffling mystery

In late June 1836, a group of boys headed out to the slopes of Arthur’s Seat in Edinburgh to hunt for rabbits. What they found there has remained a baffling mystery ever since.

In a secluded spot on the north-east side of the hill, the boys discovered a small cave. Concealed inside, hidden behind three pointed slabs of slate, were 17 miniature coffins.

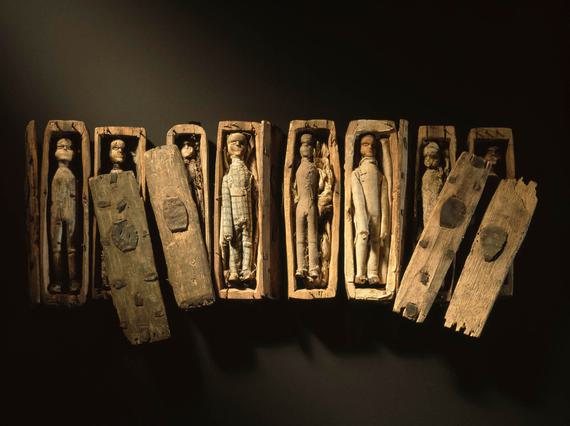

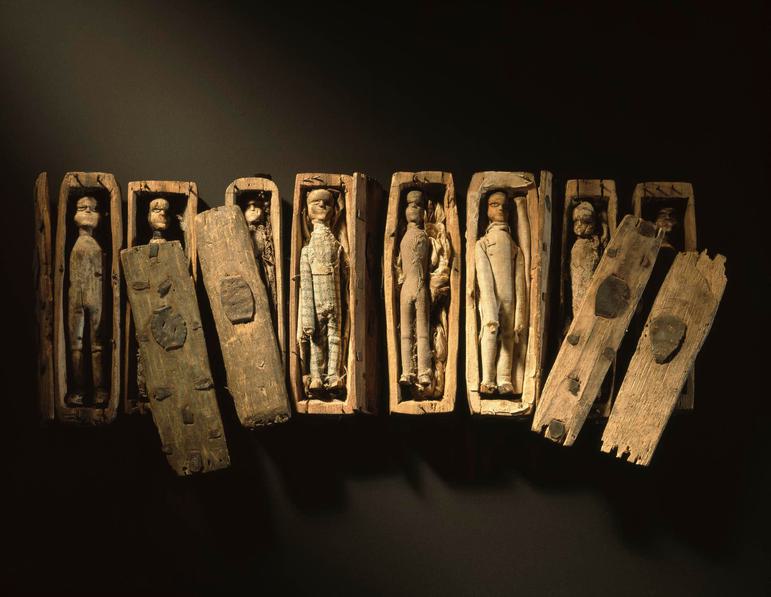

Eight of these coffins survive to the present day, and are on display in the National Museum of Scotland. Few objects in our collection excite as much intrigue.

Who made the intricate carved figures? Who did they represent? Who hid them on Arthur's Seat… and why?

Mystic coffins

Arthur’s Seat is the distinctive volcanic hill that rises up beyond Edinburgh’s Old Town. It's a place steeped in history and mystery.

It's been suggested as a possible site for King Arthur’s Camelot, and home to the Celtic Votadini tribe in 400AD. Over the centuries it’s been the scene of a medieval miracle, an 18th-century murder and a fictional encounter with the Devil.

But its strangest story began in June 1836, when a group of boys out rabbiting on the north-east side of the hill made their bizarre discovery.

Neatly arranged

The tiny coffins were arranged under slates in three tiers: two tiers of eight and one solitary coffin on the top.

Each coffin - only 95mm in length - contained a little wooden figure. The figures were carved and dressed in clothes that had been stitched and glued around them.

The collection of coffins with their lids and carved figures, found in a rocky niche on the north-eastern slopes of Arthur's Seat, Edinburgh, in June 1836.

Reports of witchcraft and demonology

What were they doing there? The newspapers of the time fell on the story, and each had a different theory.

"Satanic spell-manufactory!" cried 'The Scotsman' the first paper to report the tale, in an article published on 16 July 1836: "Our own opinion would be – had we not some years ago abjured witchcraft and demonology – that there are still some of the weird sisters hovering about Mushat’s Cairn [sic] or the Windy Gowl, who retain their ancient power to work the spells of death by entombing the likenesses of those they wish to destroy."

A month later, the 'Edinburgh Evening Post' were a little more measured. They claimed the coffins represented: "An ancient custom which prevailed in Saxony, of burying in effigy departed friends who had died in a distant land."

The 'Caledonian Mercury' added that: "We have also heard of another superstition which exists among some sailors in this country, that they enjoined their wives on parting to give them “Christian burial” in an effigy if they happened [to be lost at sea]."

Yet if this is the case, why so many similar coffins? Nobody had any answers.

What happened next?

The Arthur's Seat coffins passed into the hands of private collectors. They reappeared in 1901, when eight were donated to the Museum of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, and from there to National Museums Scotland.

What happened to the remaining nine? 'The Scotsman'reported that "a number" were destroyed by the boys, although we don’t know how many. No more have come to light since.

On surveying the evidence from 'The Scotsman', 'Edinburgh Evening Post'and 'Caledonian Mercury', cuttings from which were donated with the coffins, the Society concluded that "the intention [of the coffins] seems to be to symbolise honorific burial".

But the mystery has not been allowed to rest there.

A vanishing man

Five years later in 1906, 'The Scotsman' published another bizarre story about the coffins.

A "lady residing in Edinburgh" had told the paper that her father ("Mr B.") had sometimes been visited at his business premises by a "daft man". The man had once drawn on a piece of paper a picture of three small coffins, with the dates 1837, 1838 and 1840 written underneath.

"In the autumn of 1837, "'The Scotsman'explains, "a near relative of Mr B’s died; in the following year a cousin died and in 1840 his own brother died. After the funeral, the daft deaf mute appeared again, walked into Mr B’s office and 'glowering' at him vanished never to return."

"Is it not just possible," the article goes on to ask, "that this man was the maker of the Arthur’s Seat coffins, "driven mad by the loss of his treasures" ? Or was the whole story "nothing but coincidences"?

It's a very strange twist to the tale.

The Arthur's Seat coffins.

Seafaring talismen?

Fast-forward to 1976 and Walter Hävernick, the Director of the Museum of Hamburg History, had come up with a new theory.

It's a German seafaring superstition to keep mandrake roots or dolls in tiny coffins as talismen. So, Hävernick suggested that the coffins were a hoard of lucky charms. He thought they were hidden in the hillside by a merchant, to be sold on to sailors.

The use of charms persisted in Scotland well into the 19th century. But, no evidence of this particular seafaring tradition has been found in Scotland.

The Scottish charms below can be seen alongside the Arthur’s Seat coffins in the National Museum of Scotland

Examining the evidence

The coffins were only analysed in more detail in the 1990s, by Professor Samuel Menefee and Dr Allen Simpson, a curator at the museum. Both were Visiting Fellows at the School of Scottish Studies at the University of Edinburgh.

Here’s what they discovered:

- The figures all appear to be made by the same person. Although, it’s possible the coffins were crafted by two different people.

- Some of the materials and tools used – iron embellishments, nails, a sharp, hooked knife – indicate the coffins could have been made by a shoemaker.

- The figures seem to form a set, and their upright bearing, flat feet and swinging arms suggest they may have been toy soldiers. Their eyes are open, making it unlikely they were originally designed as corpses.

- Some of the figures are missing their arms – perhaps removed so that they would fit in the coffins.

- The fabric the little bodies are dressed in dates from the early 1830s, so they hadn’t lain buried for more than six years.

So we know where the bodies came from, and we know when they were buried.

But what do they represent?

The Arthur's Seat coffins.

Stepping back in time

Edinburgh had much to boast about in the early 19th century. It was celebrated as the seat of the Scottish Enlightenment, and had been transformed by the creation of the Georgian New Town. In 1822, Edinburgh was graced by the first visit of a reigning monarch since 1650.

Yet the city also had a dark side. There was a sharp division between the elegant, well-to-do New Town and the more densely populated, overcrowded Old Town.

A shortage of bodies

By the early 1800s, Edinburgh was renowned as a centre of medical excellence. Its reputation as a place to study the healing arts was second to none. Key to this education was an understanding of anatomy, but cadavers for dissection were becoming increasingly hard to come by.

With more and more students thronging the anatomy theatres and fewer criminals meeting their end on the gallows - the usual source of bodies for the dissecting table - the supply was no longer meeting the demand.

Unscrupulous criminals saw a gap in the market. The practice of body snatching – digging up bodies from churchyards and selling them to anatomists – became rife across the country.

Grieving relatives, desperate to protect their dead from body snatchers, would encase coffins in locked iron mortsafes for the first six weeks after burial. An iron collar, from Kingskettle in Fife, was found bolted through the bottom of a coffin and around the neck of a corpse in 1820.

Those who couldn’t afford the cost would set up vigil in the graveyard instead.

Yet the corpses sold by the infamous body snatchers Burke and Hare to renowned Edinburgh anatomist and lecturer Dr Robert Knox, came not from grave robbing, but from murder.

Burke and Hare victims?

Some have suggested a link between the Arthur's Seat coffins and the infamous Burke and Hare murders.

There are seventeen coffins, and there were seventeen Burke and Hare victims. The coffins were buried just a few years after Burke and Hare’s sensational story had hit the headlines. Could the coffins be a substitute burial for the poor, friendless souls dispatched by the murderous pair?

While twelve of Burke and Hare’s victims were female, the corpses in the coffins are all dressed as men, but perhaps the figures were simply meant as symbols.

And if they were, who buried them? Someone close to the murders, or a sympathetic onlooker? We’ll never know.

The XVIII mystery

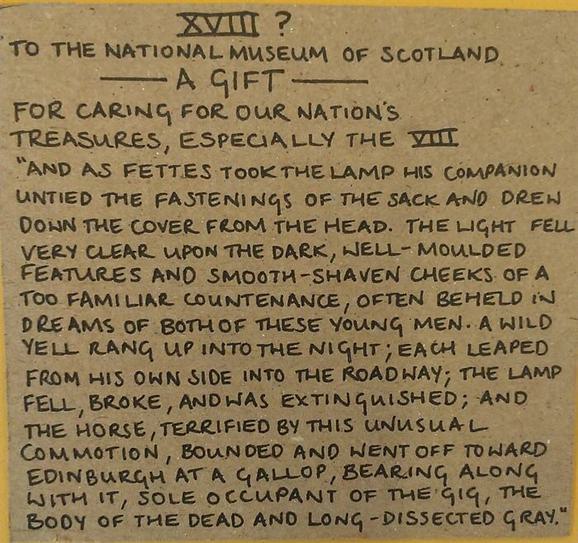

In December 2014, the Museum received a mysterious package: a beautifully-made replica of one of the coffins, cryptically entitled ‘XVIII?’

Attached was a label, quoting the chilling climax of Robert Louis Stevenson’s short story ‘The Body Snatcher’ (1884), which weaves elements of the Burke and Hare story into a chilling supernatural tale.

Coffin number 'XVIII', sent to the National Museum of Scotland in December 2014.

The label attached with coffin XVIII. It quotes Robert Louis Stevenson's short story, 'The Body Snatcher' (1884).

The Falls

Since the coffins found their way into the museum collections, they have been on display almost constantly, and continue to fascinate visitors today.

One such visitor was the author Ian Rankin, who references the coffins in his Inspector Rebus thriller 'The Falls' (2001).

In the introduction to the book, he explains how a member of staff alerted him to their presence:

"Plenty of people over the years have come up to me with their excited notions of plots for my next book. I’ve found precious few of them to be helpful, or viable, but I was intrigued by these ‘little dolls’… which is how I made the acquaintance of the Arthur’s Seat coffins… As soon as I saw them, I knew they would make a great story, especially as no one had come up with an incontrovertible interpretation of their meaning. In other words, there was a story to tell about them…"

In 2006, the novel was adapted for television and replicas of the coffins were made for filming.

Mystery: unsolved

And so the story stands. It's a mystery that will probably never be unraveled, but it's captured the imagination of countless visitors to the National Museum of Scotland.

Dead and buried? Not quite.

The Arthur's Seat coffins are on display on Level 4 of the Scotland Galleries at the National Museum of Scotland.