The controversial letters associated with the Mary, Queen of Scots Casket

News Story

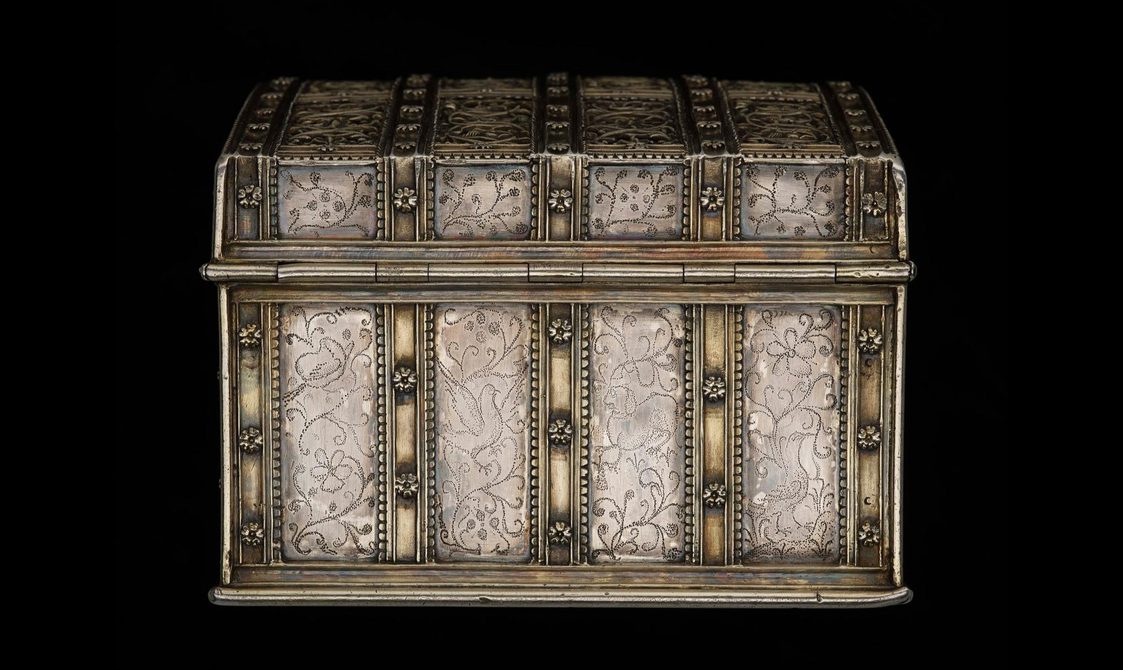

The Mary, Queen of Scots Casket is one of Scotland’s most cherished treasures, thanks to its long-standing association with the controversial queen.

The Mary, Queen of Scots connection

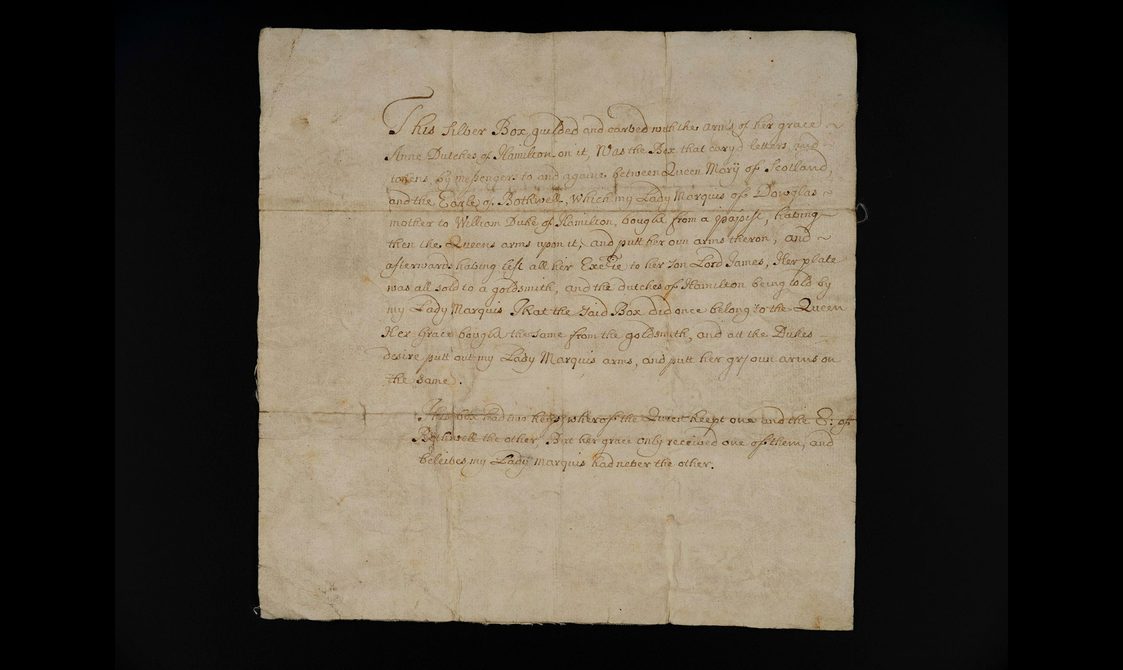

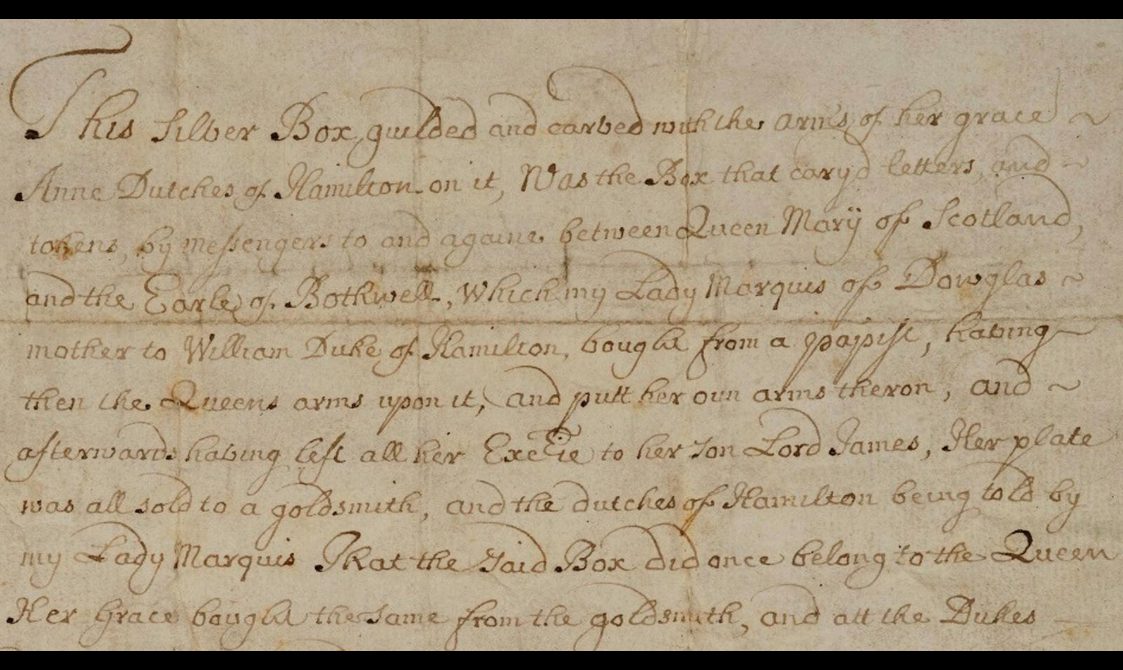

For over 300 years, a handwritten letter telling the history of the casket has been stored within it. This note records that the casket was bought by Anne, Duchess of Hamilton. She been told by its previous owner, Mary, Marchioness of Douglas, that the casket had belonged to Mary, Queen of Scots. It is this long-attested association with one of Scotland’s most famous historical figures that gives the casket its special significance.

Handwriting analysis has shown that the letter was written by David Crawford, secretary to Duchess Anne. He wrote the letter before the duchess’s death in 1716. Crawford wrote that “the Duchess of Hamilton being told that by my Lady Marquis that the said box did once belong to the Queen Her Grace bought the same from the goldsmith” after the marchioness’s death in 1674.

Image gallery

The provenance note in highly legible, italic cursive handwriting.

A closeup of the provenance note detailing the association with Mary, Queen of Scots and the silver casket's alleged provenance.

The Marchioness of Douglas had left it to her younger son, James, who promptly sold it. On hearing this, the Duchess of Hamilton, who had married the marchioness’s older son William, retrieved it from the goldsmith.

The note shows, therefore, that the casket has been believed to have been owned by Mary since at least the mid-1600s. Ever since, it has been carefully preserved by the Dukes of Hamilton who have treasured it as a relic of the queen.

Over the centuries, its association with Mary and the belief that she owned, touched, and used this casket, has given it a reverential quality. It is a physical connection to the long dead queen, an enduring reminder of Queen Mary’s dramatic life.

The 'Casket Letters'

The casket is also associated with a momentous period in Mary’s life. The provenance note records that it “was the box that carried letters and tokens by messengers to and again between Queen Mary of Scotland and the Earl of Bothwell”. Bothwell was Mary’s third husband. She married him after the murder of her second husband Henry, Lord Darnley, in 1567. The note demonstrates the belief that this casket contained the infamous ‘Casket Letters’.

Shortly after Mary was overthrown by the rebellious Confederate Lords in June 1567, a silver-gilt casket was seized by the Earl of Morton from one of Bothwell’s servants. He brought it before the Scottish Privy Council in Edinburgh and forced its lock to examine its contents. There is no record from then of what it contained.

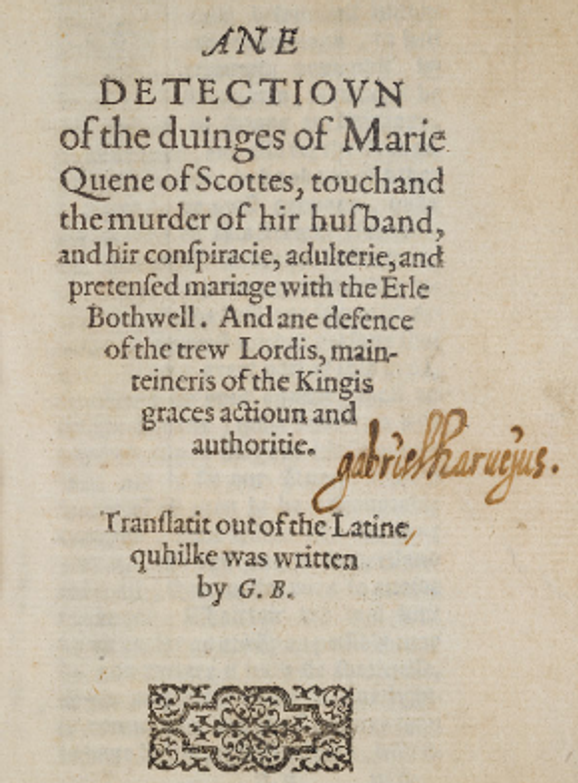

The ‘Casket Letters’ and the accusations against Mary were published by George Buchanan in his 1571 book. It was titled 'Ane detectioun of the duinges of Marie Quene of Scottes: touchand the murder of hir husband, and hir conspiracie, adulterie, and pretensed mariage with the Erle Bothwell'.

The ‘Casket Letters’ and the accusations against Mary were published by George Buchanan in his 1571 book, 'Ane detectioun of the duinges of Marie Quene of Scottes: touchand the murder of hir husband, and hir conspiracie, adulterie, and pretensed mariage with the Erle Bothwell'.

Following Mary’s flight to England in 1568, the casket was produced at a hearing against her at Westminster. It was found to contain letters alleged to be between Mary and Bothwell, and some love sonnets.

This hearing had been ordered by Elizabeth I to investigate accusations against Mary of conspiring with Bothwell to murder Lord Darnley. The ‘Casket Letters’ were used as evidence of Mary’s guilt, and of an adulterous relationship with Bothwell while Darnley was alive. They were revealed by Mary’s half-brother James, Earl of Moray. His own interests would prosper if Mary was found guilty. Although nothing was ever proven, Mary remained in English captivity until her execution in 1587, nearly nineteen years later.

It cannot be categorically proven or unproven that the Mary, Queen of Scots Casket belonged to Mary, or that it was the ‘Letters’ Casket. However, the Dukes of Hamilton have believed for at least 340 years that the casket was the ‘Letters’ casket, as did the Marchioness of Douglas before them.

It is this historical belief in the casket playing such a prominent role in Mary’s downfall that gives it an extra layer of meaning. It connects those who see it today to those disastrous moments in Mary’s life over 450 years ago.

Image gallery

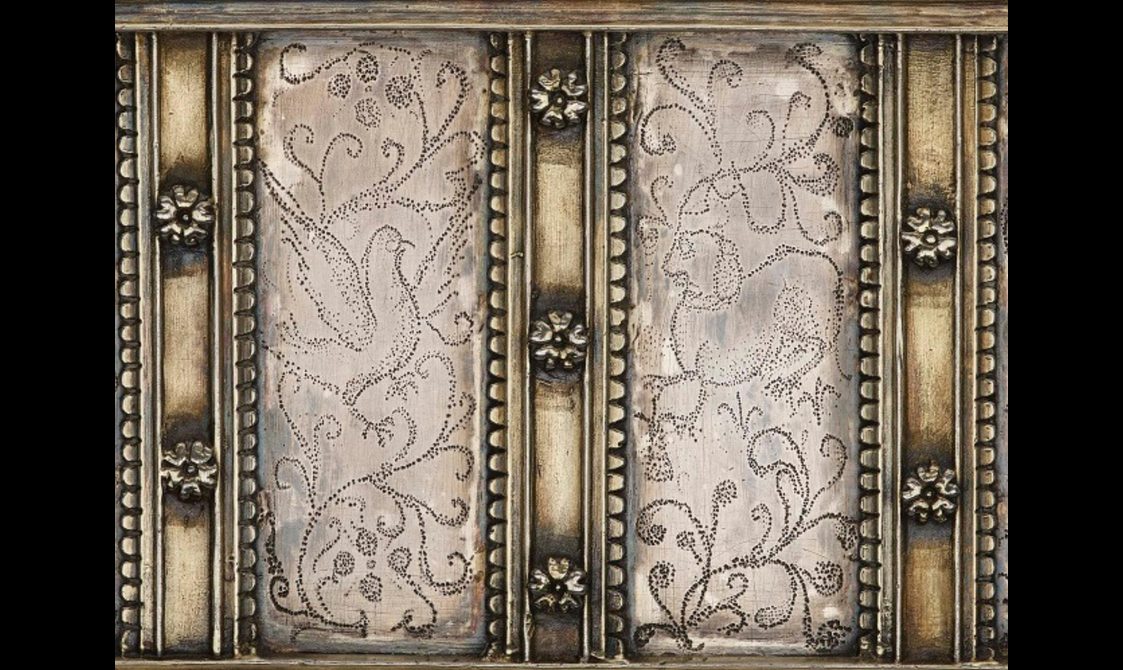

Pin-pricked designs on the casket's side.

The Parisian maker's mark, comprising a crowned fleur-de-lis atop a fire-steel and cross.

A stag and hound form one of the scenes across the casket's surface.

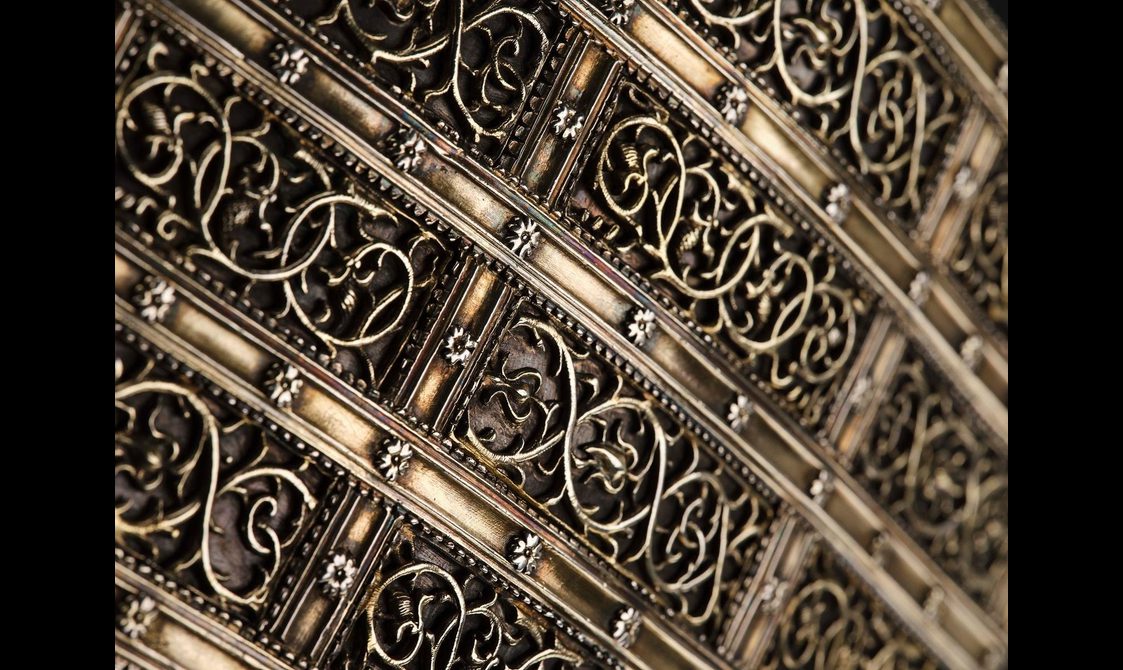

Closeup of strapwork on the casket's lid.

Strap work on the casket's lid.

Closeup of pin-pricked designs on the casket's side.

Relic of an iconic queen

Elizabeth famously called her cousin Mary, Queen of Scots, ‘the daughter of debate’. Mary was a controversial figure in her own lifetime. She stirred up fierce loyalty in her supporters and equally impassioned opposition from her enemies.

Mary continues to inspire similarly strong reactions today. Myth and mystery continue to obscure the reality of who she was, and what she was supposed to have done. The authenticity of the Casket Letters remains hotly debated.

Films, plays, operas, countless novels and whodunnits recount the drama of her life. Items associated with her, or made subsequently in her memory, are numerous. The Mary, Queen of Scots Casket, however, is a particularly magnificent example of an object through which Mary has been commemorated.

Mary, Queen of Scots by François Clouet. Royal Collection of the United Kingdom, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

It tells us of a majestic Mary, Queen of Scots, who was also briefly Queen of France (1559-1560). She was a queen almost from birth, educated to rule. She was furnished with the trappings of a Renaissance monarch who bought, was given, and inherited precious jewels and objects like the casket. The casket reveals a different Mary to the one dressed dolefully in black in posthumous portraits. It shows us a vivacious, youthful, pearl and silk-adorned Renaissance Queen.