The enigmatic origin of a beautiful igneous rock

News Story

Standing nearly two metres tall with a busy patterned surface, the orbicular granodiorite is as striking as it is rare. There are thousands of areas of igneous rocks across the earth, but we only know of less than 200 occurrences of this type of rock. These include sites in Finland, Chile, the Channel Islands and France, as well as Australia.

From Australia to Scotland

Boogardie Station is a small settlement in the outback of Western Australia. With the nearest city Perth over 550 km away, it’s safe to say that it’s fairly remote. But this region of Australia is really important geologically as it contains ancient parts of the earth’s crust. In fact, some material mined from the quarry there is over 2.6 billion years old.

Australia is one of the few places on earth where orbicular rock is found. Luckily, a superb sample of rock from Boogardie Station found its way to Edinburgh. This rare specimen stands 1.7m high, weighs a hefty 870kg, and as far as we know, it is the largest of its kind in the UK.

Emily Brown, assistant curator of earth systems at National Museums Scotland, with a piece of orbicular granodiorite.

What’s so special about orbicular granodiorite?

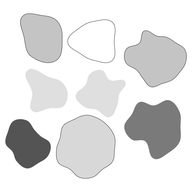

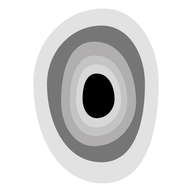

Granodiorite is a kind of igneous rock containing quartz, plagioclase feldspar, and some other minerals in lesser quantities. It forms from the cooling and crystallisation of magma (molten rock) deep within the Earth’s crust. Usually it forms a plain grey speckled rock. But sometimes, granodiorite is found full of these mysterious concentric orbs. This is orbicular granodiorite.

How is it formed?

Scientists have yet to agree on how these orbs are formed, but a few theories have been suggested. It could be related to the rate at which the magma cooled while it was solidifying underground. Magma that cools slowly tends to grow larger crystals than quickly-cooling magma, which tends to form smaller crystals.

Formation of the orbs could also be related to the amount of water in the magma. Water affects the crystallisation temperature of magma, as well as the way is can flow and deform when partially solid. We can tell the orbs were still squashy and pliable after they formed because they are not perfectly spherical.

Another possible factor is the way the solid particles cling together as they grow. This concept is called nucleation and it’s the same process that controls the growth of hailstones in a thundercloud. If it is more efficient for new crystals to grow on already-existing solid particles than on their own in the liquid magma, they may clot together and form these large round masses.

However the orbicular granodiorite forms, it must require very specific and uncommon conditions. This is why it is so rare and specimens like this spectacular one are so unusual!

A vlose up of orbicular granodiorite.

See this mysterious rock for yourself

The orbicular granodiorite (museum reference G.2008.19.1) is on display in the Restless Earth gallery at the National Museum of Scotland. This gallery shows the series of events and processes that transformed the Earth from a barren, rocky planet to the diverse planet we know today.