The history and revival of Indonesian pink barkcloth

News Story

Pink-dyed barkcloth from Central Sulawesi captivates with its vibrant colour. Discover the cultural role, production, and modern adaptations of barkcloth in this part of the Indonesian archipelago.

Where is Central Sulawesi?

The island of Sulawesi forms part of the Greater Sunda islands along with Sumatra, Java, and Borneo. It is the fourth largest island in the Indonesian archipelago and the eleventh largest island in the world.

Sulawesi has a long colonial history. It was named ‘Celebes’ by the Portuguese in the early 16th century. The Dutch and English followed in the early 17th century, and the island was part of the Netherlands East Indies between 1905 and the Second World War. At this time it was occupied by Japan. Sulawesi finally became part of the newly independent nation of Indonesia in 1950.

Mountains covered in clove plantations in Toli-Toli, Central Sulawesi.

The island has an unusual shape and is often compared to an orchid. It has vast lengths of coastline and a mountainous, volcanic interior. This topography has meant that the inland and highland populations remained isolated until the 20th century. Colonial-led missionary activity saw these areas become predominantly Christian. In contrast, people living in lowland and coastal areas had access to long-distance trade networks and are predominantly Muslim.

The role of barkcloth in Central Sulawesi

Over centuries, different regions in Sulawesi have developed distinctive and varied forms of traditional dress that continue to be worn today for special occasions such as weddings. The barkcloth garments in our collections come from the highland communities of Central Sulawesi. Here barkcloth was commonly used for everyday and ceremonial clothing until the end of the nineteenth century.

Multi-layered skirts, tunic-shaped blouses, and loincloths for daily use were made from a plain, brown barkcloth that was durable and warm. In contrast, clothes for special and religious occasions were made from soft, fine, white barkcloth. They were painted with bold, symbolic designs and bright colours. Our collections contain intricately patterned sigas (men’s headdresses) and halili (women’s blouses). These were designed to be worn at feasts and important life events.

Image gallery

Siga or men's headdress of barkcloth, painted with a brightly coloured pattern, worn at feasts. Asia, South East Asia, Indonesia, Central Sulawesi, Kulawi or Bada, early 20th century. Museum reference V.2019.34.23.

Tali or headdress of barkcloth worn at the back of the head. Asia, South East Asia, Indonesia, Central Sulawesi, Kulawi or Bada, early 20th century. Museum reference V.2019.34.20.

Siga or men's headdress of barkcloth, painted with a brightly coloured pattern, worn at feasts. Asia, Southeast Asia, Indonesia, Central Sulawesi, Kulawior Bada, early 20th century. Museum reference V.2019.34.25.

Halili or women's blouse of black barkcloth decorated with coloured patches and embroidery. Asia, Southeast Asia, Indonesia, Central Sulawesi, Kulawi or Bada, early 20th century. Museum reference V.2019.34.30.

Siga or men's headdress of barkcloth, painted with a brightly coloured pattern, worn at feasts. Asia, South East Asia, Indonesia, Central Sulawesi, Kulawi or Bada, early 20th century. Museum reference V.2019.34.24.

They are decorated in different ways. Some are painted with dye, others sewn with applique, and some embellished with sequin-like flakes of a mineral called mica. Styles varied between regions, but often included geometric motifs and symbols of buffalo horns, four-petalled flowers, diamonds, and suns.

Colours and patterns are thought to have been associated with important ideas, such as courage, vitality, and prosperity. The cloth also contained important spiritual and protective values. Men’s headdresses often denoted rank and status. Women wore particular garments for transitional life events, such as childbirth or periods of mourning. The barkcloth tradition of Central Sulawesi is notable as being one of the most refined barkcloth production systems ever developed.

How was barkcloth made in Central Sulawesi?

Barkcloth making is a tradition that dates back 4,000 years. Making barkcloth, known as ranta or fuya, was a long process that took several weeks. It was completed mainly by women. The process started with identifying suitable trees, often a variety of ficus, and stripping lengths of inner bark from branches and trunk. The bark was boiled, beaten, soaked and left to ferment for several days. This process rendered the bark pulp sticky and malleable. This substance was then beaten vigorously to fuse it into a smooth cloth-like material.

The barkcloth would be flipped, rotated, and beaten with wooden mallets. The process would often end with small stone beaters to refine the finish. Strips were beaten together to make larger pieces. The finished cloth would be painted with a type of plant sap or resin to preserve and strengthen the surface. Finished cloth could not be washed. Although daily wear could last for seven or eight months, ceremonial clothing only lasted for short periods of time before it disintegrated.

A modern barkcloth producer in Central Sulawesi employs traditional production methods inside a barkcloth workshop.

Think pink

The eye-catching pink colour of the barkcloth pieces in our collection was achieved by using a synthetic organic dye, Rhodamine B. It was invented by Maurice Ceresole (1860-1936) and patented by him in France in 1889.

Be it known that I, MAURICE CERESOLE, doctor of philosophy, a citizen of the Swiss Republic, residing at Neuville, in the Department of the Rhone, France, have invented new and useful improvements in the Manufacture of a New Red Dye-Stuff of the Rhodamine Class.

Maurice Ceresole

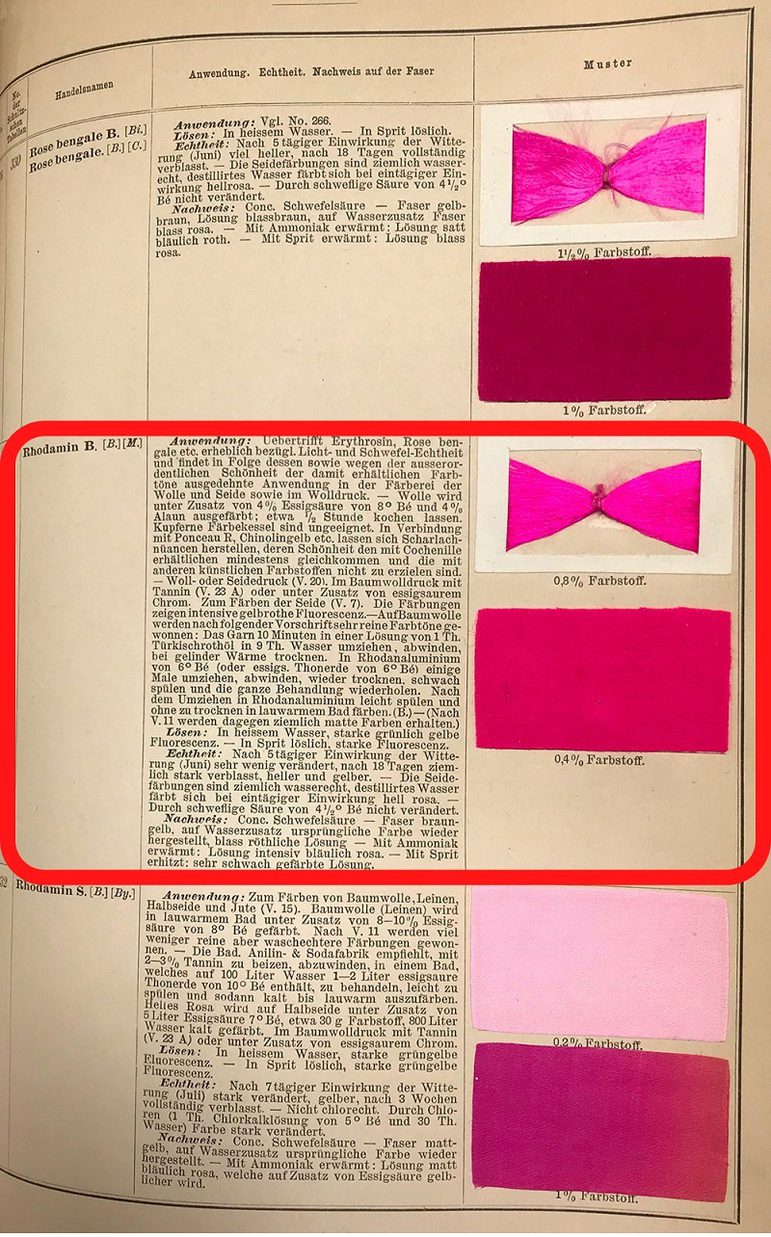

Ceresole’s Rhodamine B created mainly yellowish-red shades. On silk fabrics it showed a “striking fluorescence”. The German chemist, Dr Adolf Lehne (1856-1930) tested the dyestuff for its application in the textile industries at the time. He admired the “extraordinary beauty” of its colours. It might have been a combination of these two qualities which prompted barkcloth makers in Central Sulawesi to test the dye for its suitability on fibrous bark.

Rhodamin B test results (centre) published by Adolf Lehne in “Tabellarische Übersicht über die künstlichen organischen Farbstoffe und ihre Anwendung in Färberei und Zeugdruck” in 1893.

This was not the first time that new dyes were incorporated in the making process of barkcloth in this area. During the 19th century, pink, or crimson was already a prominent colour of locally made barkcloth. Common sources of yellow and orange dyes in Southeast Asia that might have also been used for barkcloth were safflower (Carthamus tinctorius) and the seeds of Bixa orellana, commonly known as annatto.

Annatto is a tree indigenous to Central and South America which was introduced to South and Southeast Asia during the colonial time. The Dutch began to plant annatto trees along the roadsides in Java in 1828 to produce dye for export to Europe. However, this made the orange dye also available in Southeast Asia. Did you know that we still use annatto to colour Shropshire Blue and Mimolette orange today?

The use of natural dyes has been revived in contemporary barkcloth production. Reds and pinks dominate the colour palette. In Bada Valley, located in Lore Lindu National Park, barkcloth makers hand paint the barkcloth with berries from the binahong vines (Anredera cordifolia) to produce a pink colour. It is also used to dye coixseeds or ‘job’s tears’ which are then incorporated into jewellery and accessories. A native plant called llimbi or bola is also used. That dyeing process requires at least one week to attain pink, red, and maroon colours.

Early 20th century decline and modern resurgence

In Central Sulawesi, barkcloth production began to dwindle from the early twentieth century. Imported cloth became more widely available at this time. This woven cloth was often preferred as it was less labour intensive and lasted for longer as it could be washed.

The decline of barkcloth was also due to an increased Dutch colonial presence in the region and the establishment of Christian missions. Pre-existing belief systems and ways of life, including the production and use of barkcloth, were discouraged. Many began to view barkcloth as old fashioned and embarrassing. Although for some its continued production became a symbolic form of resistance against colonial intervention. During the Second World War, Japanese occupation of the island created textile shortages. Many women returned to making barkcloth to clothe their families.

Today, the Lore region of Central Sulawesi is one of the last places that still produces barkcloth in Indonesia. It is predominantly produced by senior women in a few remote communities. Barkcloth is still worn for special occasions such as weddings, and has become recognised and appreciated as a distinctive cultural heritage. Promoted as part of governmental development and tourism projects, makers from Central Sulawesi have exhibited their cloth in national museums and private galleries in Jakarta and New Zealand.

Contemporary barkcloth being made in the Lore Valley, Lembah Bada, Central Sulawesi.

The rich history of Sulawesi barkcloth has also caught the attention of contemporary artists. Inspired by historical collections in European museums, Indonesian-based artist Mella Jaarsma has used barkcloth from Sulawesi to create costumes and installations. For her 2017 project 'I Owe You', Mella learned how to make barkcloth. She located a village in the Lore Valley of Central Sulawesi where colonial missionaries converted villagers to Christianity, suppressing barkcloth production and use. Barkcloth thereby became an aspect of resistance, and is still made and worn there today.

'I Owe You II', costumes by Mella Jaarsma of barkcloth made from lantung tree and digital print on fabric containing speakers.

'I Owe You IV', two costumes by Mella Jaarsma of barkcloth made from mulberry, ficus and malo trees, fibre glass, stainless steel, wood and cotton textiles.

Industrial textile production has contributed to the decline of barkcloth’s traditional use as everyday clothing. However, small scale producers are finding new markets. They promote the value of natural and sustainable materials.

Bali-based Cinta Bumi Artisans partner with barkcloth co-operatives in Central Sulawesi and buy sheets to make into bags and accessories. Their work promotes barkcloth as a positive alternative to the pollution and exploitation of mass produced ‘fast’ fashion.

In this way, the story of Indonesian barkcloth continues as it finds new relevance and value in the contemporary world.