The life, death, and legacy of Mary, Queen of Scots

News Story

Arguably the most famous and controversial figure in Scottish history, Mary Stewart has become something of an enigma. Intrigue and romance have often obscured the hard facts of her life and reign.

The only daughter of the late James V of the ruling Stewart dynasty, Mary became Queen of Scots at only six days of age. She reigned from 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567. After 19 years as a prisoner of her cousin, Elizabeth I of England, Mary was executed on 8 February 1587.

Unlike Elizabeth, there was never any doubt that Mary would be a queen. Born in the middle of the momentous 16th century, Mary was to play her own significant part in this dramatic era. The expectation that she was born to rule extended to her burning ambition to be named as Elizabeth’s heir to the throne of England. This desire came to dominate Mary’s relationship with Elizabeth, and would prove to be a dangerous obsession which would bring about her death.

In my end is my beginning

Towards the end of her life, during her time in captivity as Elizabeth’s prisoner, Mary embroidered the following epitaph-like motto: “In my end is my beginning”. This has proved to be somewhat prophetic. More than 400 years after her death, Mary’s legacy still provokes passionate and heated debate. Was she a willing agent or a wronged victim in some of the more controversial episodes of her life?

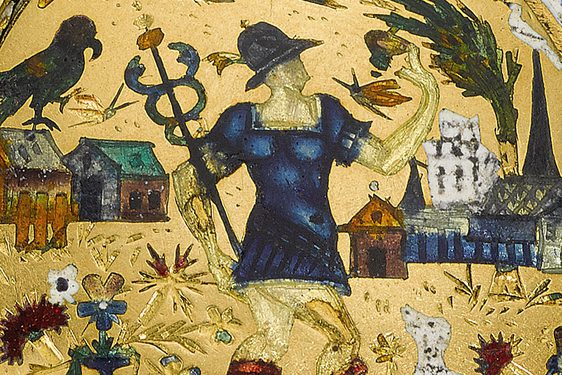

The Blairs Memorial Portrait of Mary, Queen of Scots.

Auld and New Alliances

Early-modern Europe was dominated by large dynastic monarchies. These dynasties would seek alliances with each other to further their power. Marriage was a key element in cementing these alliances, and Mary was no exception. Despite the fact that Scotland was the poorer relation of the major European powers, Mary was important dynastically. She was used as a marriage pawn, first with England and then, more successfully, with France.

Renaissance and Reformation

Mary’s Europe was undergoing two far-reaching changes to society; the Renaissance and the Reformation. The Renaissance had a huge impact on art, architecture, literature, philosophy and science, and mainly affected Europe’s literate elite. The Reformation was a dramatic revolution in religion. These movements influenced not only everyday life, but also dramatically transformed European geopolitics. The continent was now divided into two hostile camps: Catholic and Protestant.

In Scotland, France and England, Mary was a contemporary of some of the most influential personalities of the Renaissance era. Along with Catherine de Medici, Mary Tudor, and Elizabeth I, Mary was one of a small group of women, Renaissance queens who – in an era still largely dominated by men – wielded considerable power.

Costume and jewellery

Penicuik Locket, Mary Queen of Scots. Museum reference H.NA 422.

Mary was a striking woman who knew how to present an eye-catching and regal appearance. Tall, beautiful, and graceful, with auburn hair and a fine, pale complexion, even one of her archenemies, the Protestant Reformer John Knox, described her features as “pleasing”.

Raised in one of the most sophisticated and glittering courts in Europe, she had access to the very latest Renaissance fashions. She loved fine clothing and amassed a sumptuous wardrobe of elegant and fashionable gowns and a spectacular collection of jewellery.

Jewels were essential currency for a 16th-century monarch: they displayed the majesty of monarchy and could be sold to raise cash to pay armies or debts. The gold necklace, locket and pendant, known collectively as the Penicuik jewels, are exquisite examples of some of the finest pieces of jewellery associated with Mary.

A murder and a marriage

The Memorial of Lord Darnley, 1567-68

In the small hours of 10 February 1567 an enormous explosion destroyed the lodgings at Kirk o’ Field in which Darnley, Mary’s husband and King Consort, was staying. The bodies of Darnley and his servant were found in the rubble of the building. Darnley had been murdered in mysterious circumstances, and Mary herself was implicated in the plot.

The prime suspect was the man who was to become Mary’s third husband: James Hepburn, Earl of Bothwell. How Mary dealt with this incident sealed her fate.

Mary left Edinburgh with Bothwell after Darnley's death in contested circumstances. Bothwell would later be tried for murder, but was exonerated. However, suspicions about Mary's involvement in Darnley's death led to her losing support, and ultimately the Scottish crown. In 1568 the Casket letters - which implicated Mary in the murder of Darnley - were cited to assert her guilt.

Having been captured by enemies in 1567, Mary was held prisoner until she was implicated in the Babington plot against Elizabeth I in 1586. In 1587 Mary was convicted of treason and executed.

Rejoice don’t weep

These words of comfort were spoken by Mary to one of her servants as she faced execution.

In a sense Mary won through in the end; her son James VI of Scots became James I of England on the death of Elizabeth in 1603. Thus, every reigning British monarch since then has been descended from Mary, rather than from Elizabeth, who died childless. So perhaps we can indeed agree with Mary’s prophetic epitaph: “In my end is my beginning”.