The Newcomen engine and its role in Britain’s industrial revolution

News Story

Towering 9.5m high and weighing 20 tonnes, the Newcomen engine in our collection is a part of the story of the industrial revolution in Britain.

Thomas Newcomen developed this type of engine in 1712 in response to the problem of water in mines, which limited the volume of minerals that could be extracted. The Newcomen engine was used to pump the water out. This made it possible to mine deeper and reach more of the minerals that were key to the industrialisation of Britain. Coal in particular was vital to the massive increase in manufacturing by machine that happened during the 18th and 19th centuries.

There were at least 100 engines of this type in use across Europe by the time Newcomen died in 1729. The engine was the precursor to James Watt's steam engine.

How does it work?

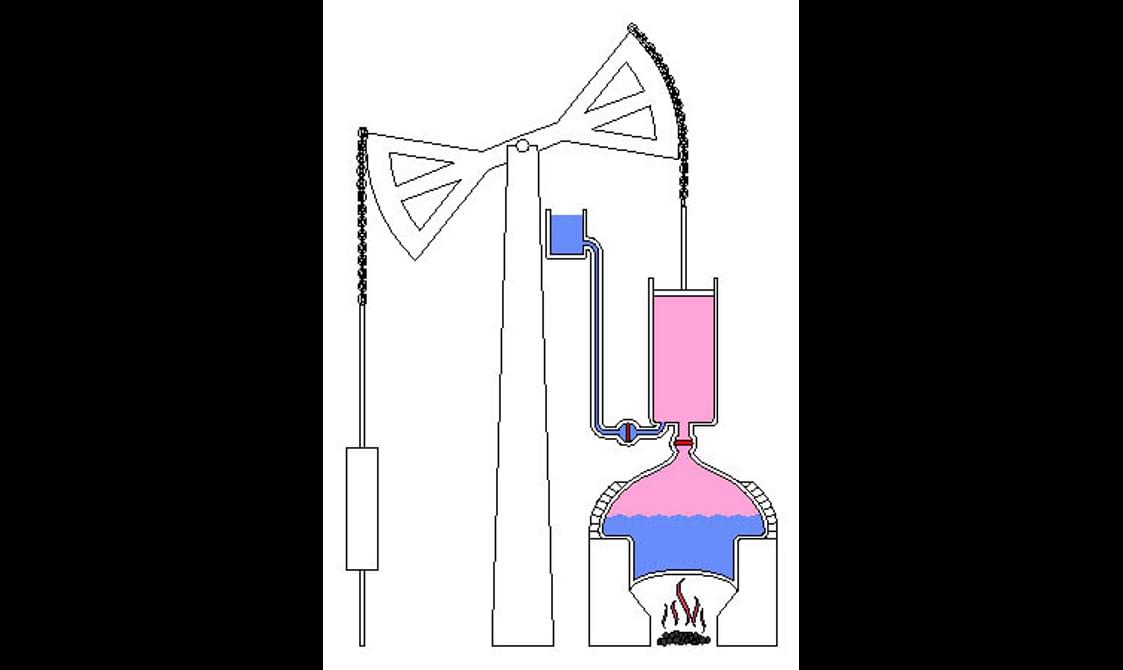

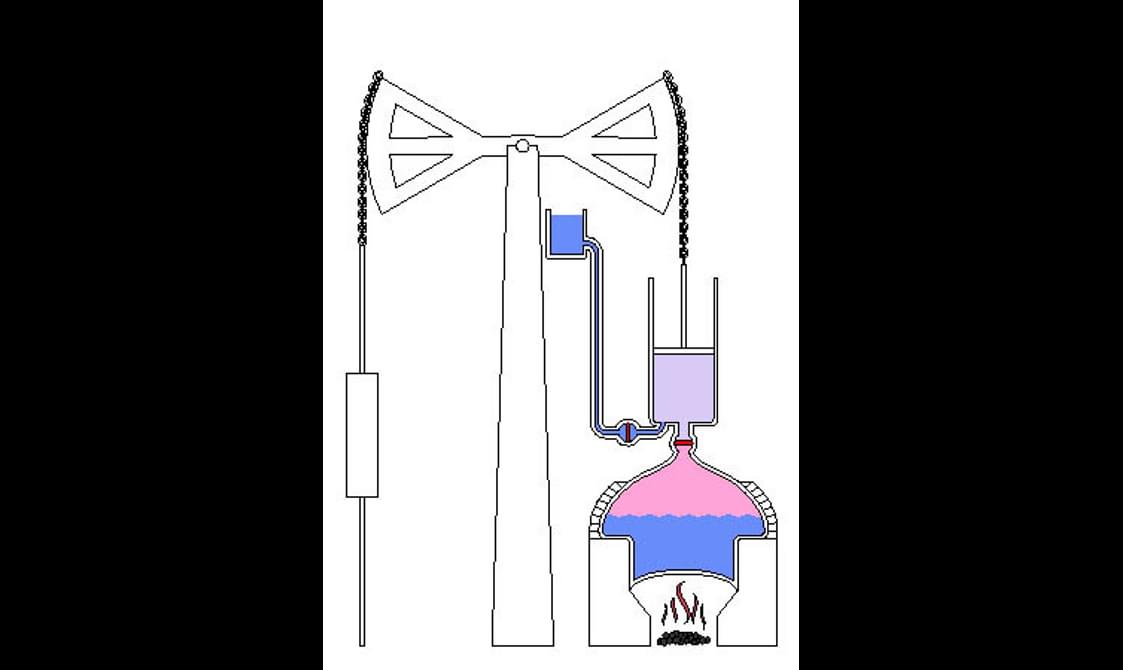

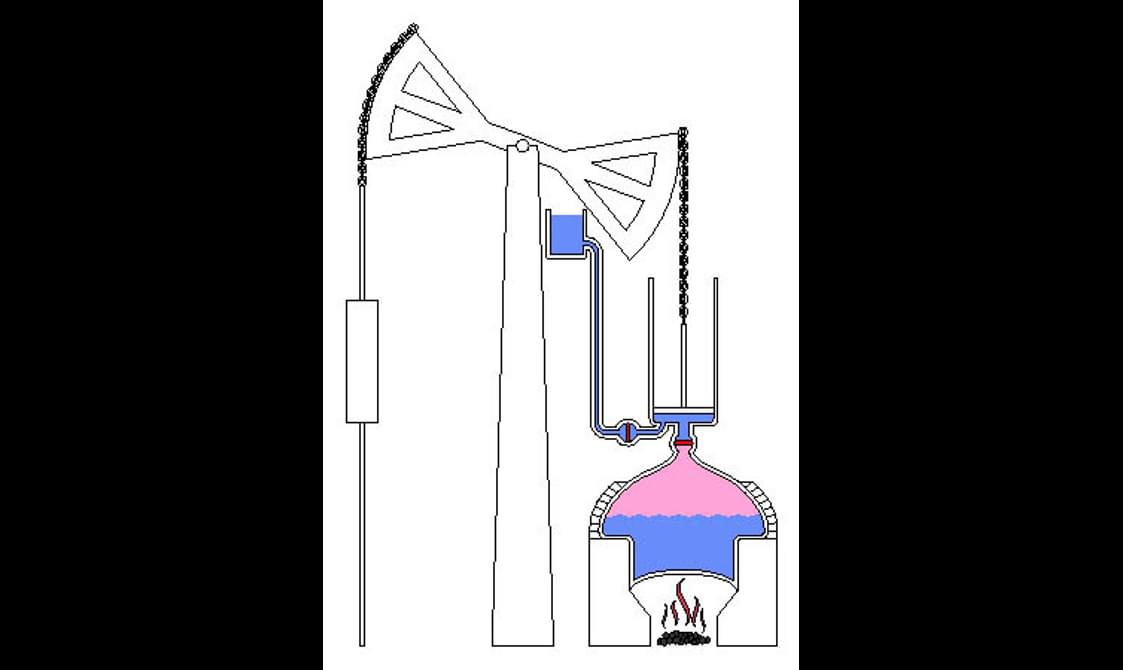

The Newcomen engine utilised a piston working within an open topped cylinder. The piston is connected by chains to a rocking beam. At the other end, the beam is connected to the pumps in the mine by a rod.

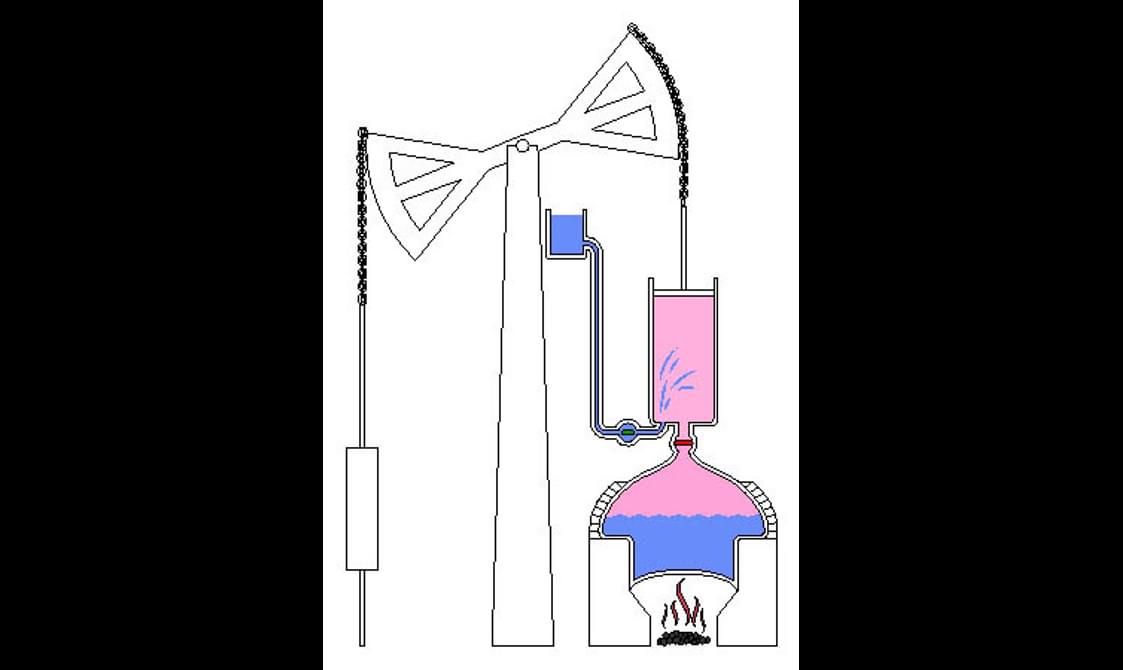

On the outboard stroke, the cylinder is filled with steam from the boiler and then cold water is injected into the cylinder to change the steam back to water and create a vacuum. When water turns to steam it expands 1500 times, so a contained volume of steam, if condensed back to water, will create a vacuum. The piston is pushed down by the weight of the atmosphere and, via the rocking beam, raises the plunger in the water pump.

Image gallery

1. The boiler heats water to make steam that fills the cylinder, pushing the piston up and lowering the plunger in the water pump.

2. Cold water is injected into the cylinder, cooling the steam and turning it back into water.

3. The water drains from the cylinder, creating a vacuum.

4. The weight of the atmosphere pushes the piston back down which raises the plunger in the water pump.

What is the history of our Newcomen engine?

Caprington Colliery opened in Ayrshire in the mid-seventeenth century. A colliery is a coal mine and its associated surface buildings. There were constant problems with drainage in the mine as it was located in the low-lying Irvine valley, so an engine was commissioned to pump water out. The Carron Company, Falkirk, first supplied parts for a Newcomen Engine to Sir William Cunninghame of Caprington in 1781. However, the pumping shaft collapsed in 1828 and that mine was subsequently abandoned.

Although Newcomen engines were not as efficient as Boulton and Watt engines, another was ordered from the same firm in 1811 at a cost of £352.42. This may have been because fuel (coal) was in abundance so efficiency was less of a concern.

The new engine was erected on a site near Earlston, on the Caprington estate. It drained the Blind Coal seam at a depth of 50 metres. It worked continuously for ninety years, with a replacement cast iron beam in c. 1837 and several new boilers.

The Newcomen engine in the Scotland Transformed gallery at the National Museum of Scotland.

How did the engine come to the Museum?

In 1901, the engine was replaced by electric pumps and gifted to the Burgh of Kilmarnock by Colonel Cunninghame of Caprington. Andrew Barclay & Sons were commissioned to erect the engine at the Dick Institute. It remained there until 1958, when the structure was deemed to be unstable.

The engine was then put in storage for forty years, until the opening of the new Museum of Scotland in 1998 gave it new life. It was rebuilt inside the Museum during construction. The restored engine boasted new components to replace those that were in poor condition or missing, including the original wooden parts and the engine house. The latter was designed based on existing engine houses from the period, historical documents, and photographs.

The Newcomen atmospheric steam engine (museum reference T.1958.117) can be found in the Scotland Transformed gallery at the National Museum of Scotland. It is operated by hydraulic power and you can see it in motion at various times throughout the day. The display is complemented by a working model of a Newcomen engine.