The significance of the Maharaja Duleep Singh's jewellery to the Indian and Sikh community

News Story

Maharaja Duleep Singh's jewellery

This jewellery once belonged to the Maharaja Duleep Singh, who became the last ruler of the Sikh Empire at only five years of age in 1843. As the youngest son of Maharaja Runjeet Singh (1780-1839), he inherited a large personal collection of rare diamond and emerald necklaces, bracelets, earrings, rings, and tiaras.

Pendant of gold inlaid with rubies and emeralds, beneath the central rock crystal a depiction of the Hindu goddess Durga, preceded by Hanuman, formerly in the possession of Maharajah Duleep Singh (1838-1893), northern India, probably Rajasthan, 1800 – 1850. Museum reference A.1911.471.

This jewellery is of special significance to all Indians, demonstrating the incredible skills of the artisans who created them, but also as a reminder of the British rule and colonialisation of India, and the wars, miseries and exploitation that came with it.

Duleep Singh was taken away from his mother and brought to Britain when he was 16 years old under the wings of the British Raj, who had stripped him of his Sikh and Indian identities.

During a tour to the National Museum of Scotland to view the jewellery the link to their colonial past was a topic of discussion.

The history of objects is important and we must talk about it. It was interesting to learn about the colonial history.

Members of the Networking Key Services group

A smaller group of us did some further investigations into the details of the jewellery and its connection to the British Empire.

The jewellery was bought by Major Donald Lindsay Carnegie at an auction from the son of the Maharaja, and was then bequeathed by him to the National Museum of Scotland in 1911.

The earrings are one of the pieces of jewellery in this collection. The Maharaja Duleep Singh was very fond of wearing jewellery even when he moved on to dressing up in European outfits. However, these earrings likely belonged to a woman, possibly his mother.

The exquisite earrings from the Duleep Singh collection, probably belonging to the Maharaja’s mother, northern India, mid-19th century. Museum reference A.1911.467 and A.1911.467 A.

Box for betel (pan-dan) decorated with a floral pattern, northern India, 19th century. Museum reference A.1911.464.

The other piece of jewellery is a pendant decorated with Indian rubies, emeralds and gold, depicting the Hindu deities Durga and Hanuman. For Sikhs, Hindu deities symbolise the bond and understanding between different cultures.

The third piece of jewellery is a box made to hold paan, or betel leaf. Traditionally, paan is chewed after a heavy meal to help digestion and to freshen up the mouth. The box is made of gold and has the intricate teardrop shape of a buta. Although it is well known that Sikhs do not chew paan, it is possible that as the Maharaja moved away from his culture and religion, he adopted the diverse traditions of other cultures. The theory could be that paan-dan box was a gift to him or to his father and was part of the treasury confiscated by the British.

The efforts of National Museums Scotland are highly appreciated for displaying the jewellery in the museum, looking after it, and giving wider global communities the opportunity to know about the history of Indian royalty. Major Donald Lindsay Carnegie also needs to be acknowledged for bequeathing the jewellery to the Museum. The pieces of jewellery are rare and of hugely high value, not only as a legacy of Maharaja Duleep Singh, but as a showcase for the intricate designs demonstrated in the incredible skills of the artisans who created them.

Sikh identity and belonging

Not only is the shiny valuable jewellery pleasing to the eye, but every item has historical significance. We started to research our history and explore questions like: To whom does the jewellery belong? How did the son of Maharaja Duleep Singh, Victor Duleep Singh, inherit it and why did he sell it? The main answer we know now is that the jewellery is one example of the colonial history of wars, miseries and exploitation outlined in the history books we consulted. The book ‘The Maharajah’s Box’ published an extract of Duleep Singh’s letter to The Times (p.36):

Instead of carrying out the solemn contract by the British Government at Bhyrowal; his Lordship (Lord Dalhousie) sold almost all my personal, as well as private property, consisting of jewels, gold and silver plate, even some of my wearing apparel and household furniture, and distributed the proceeds, amounting as prize money among those very troops who had come to put down a rebellion against my authority.

The book ‘The Maharajah’s Box’ published an extract of Duleep Singh’s letter to The Times (p.36).

The Times claimed “For a long time he (Duleep Singh) preferred a claim for the Koh-i-noor, of which he alleged that he had been wrongfully despoiled (The Maharajah's Box, p.36)”.

Maharaja Duleep Singh was the son of Maharaja Runjeet Singh, the king of the Sikh Kingdom of Lahore, who was called ‘sher-e Punjab', or 'The Lion of Punjab' for his bravery. He was the only king in India whom the East India Company was unable to dethrone because his army was trained by the best tutors from France, Germany and Russia. The East India Company forever had their eyes on the kingdom.

After the death of Maharaja Runjeet Singh, his son Duleep Singh was crowned king at the age of five. The kingdom was taken over by the British in a war against the Sikhs, and Duleep Singh was taken away from his mother for the fear of her influencing her son against the British. He was guided under the wings of the British Raj, with the Scottish surgeon John Login as his guardian, who heavily influenced him towards Christianity. His mother was taken hostage and imprisoned without any trial as ‘a political offender’.

The kingdom’s treasury was taken over by the British Government, but some of the jewellery was given back to Duleep Singh over a period of time. Perhaps, the jewellery mentioned here is part of the collection returned to him as a gift from his own treasury.

Duleep Singh was brought to Britain when he was 16 years old. He lived on a pension for most of his life, given to him by the British Government out of his own treasury confiscated by the East India Company. He was introduced to the Bible and was indoctrinated in Christianity. He converted to Christianity at the age of 14 when he was a minor. When Duleep Singh left for England, he was presented with a Bible by Lord Dalhousie with a message on it that read: ‘In the Bible he will find the word of God that is an inheritance richer and greater than any materialistic Kingdoms’. The irony here is that Lord Dalhousie possibly overlooked the preaching of the Bible himself when looting wealth that didn’t belong to him. The famous diamond currently set in the crown of Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother - the Koh-i-noor - was one of the items that is claimed to have been gifted by Duleep Singh to Queen Victoria – although this was done when the Maharaja was a minor.

During his teenage and early twenties, he lived in various locations in Scotland in Perthshire, including Castle Menzies and houses in Auchlyne and Aberfeldy. He was known at that time for his love of the classic Highland lifestyle – shooting parties and dressing in Highland costume.

Duleep Singh died at the age of 56 and his son Victor Duleep Singh may have inherited some of his jewellery. He sold the jewellery because he was in debt.

Lingering questions

Here are a few questions considered by the group for others to consider:

- Duleep Singh, the son of one of the richest kings in India died almost in poverty. Further, his son Victor Duleep Singh sold the jewellery to pay off his debts. How did all this happen? Were these unfortunate situations that arose because of wars, miseries, atrocities and the colonial system enforced by the British?

- Maharaja Duleep Singh was born as a Sikh and died as a Sikh, although he has been buried as a Christian in Suffolk. It is worth noting that he converted to Christianity when he was a minor, a term used today would be, indoctrinated. Should he not get a Sikh funeral?

- Maharaja Duleep Singh’s kingdom and treasury was signed over to the British when he was a minor. Does this make it legal?

We met with Friederike Voigt, Principal Curator of the South Asian collections, to explore some of Duleep Singh’s collection not on display. This was an opportunity to get close to a piece of our Sikh history and heritage.

Members of the Networking Key Services group viewing a bracelet once belonging to the Maharaja Duleep Singh.

This led us to a discussion about Duleep Singh’s dual identity as both Indian/Sikh and British and to consider our own Sikh-Scottish identity, reflecting on how complex this can be, feeling both at home yet sometimes displaced in both Scotland and India. It also made us consider how intrinsic one's cultural background is to one's identity, and how one can’t easily change this to suit another environment or culture. It must have been very hard for Duleep Singh to have his Sikh and Indian identity taken away from him at such a young age.

The Duleep Singh collection can be found in the Artistic Legacies gallery at the National Museum of Scotland.

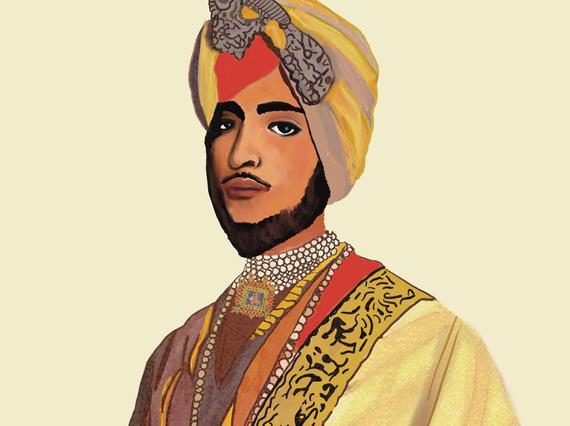

Cover illustration © Malini Chakrabarty

Written by

Members of the Networking Key Services group

In 2022 South Asian community groups supported by Networking Key Services (NKS) visited the National Museum of Scotland to view the galleries and interpret objects from the South Asian and Scottish collections.