Understanding how Margaret Tytler’s Indian models were created

News Story

Who was Margaret Tytler?

Margaret Tytler (1785 – 1822) was one of the few European women during the 18th and 19th centuries whose achievements are recorded and celebrated even today. Born and brought up in Scotland she lived in India from 1812 to 1822, where she died at the age of 37.

Her remarkable collection of models embodies the vision and enterprise of a 19th century woman entrepreneur who appreciated the value of tools from the Indian subcontinent.

Members of the NKS group discuss Margaret Tytler's model of Indian bellows.

While exploring the Scottish South Asian links via objects displayed, the South Asian community group who was engaging with museum collections participated in a fruitful discussion about and interest in colonial history. Some of the comments from the group participants included “It is fascinating and enlightening; all the information is new to me”, “Our purpose should be to explore Indo-Scottish links”, and “I would like to be part of the colonial history group.”

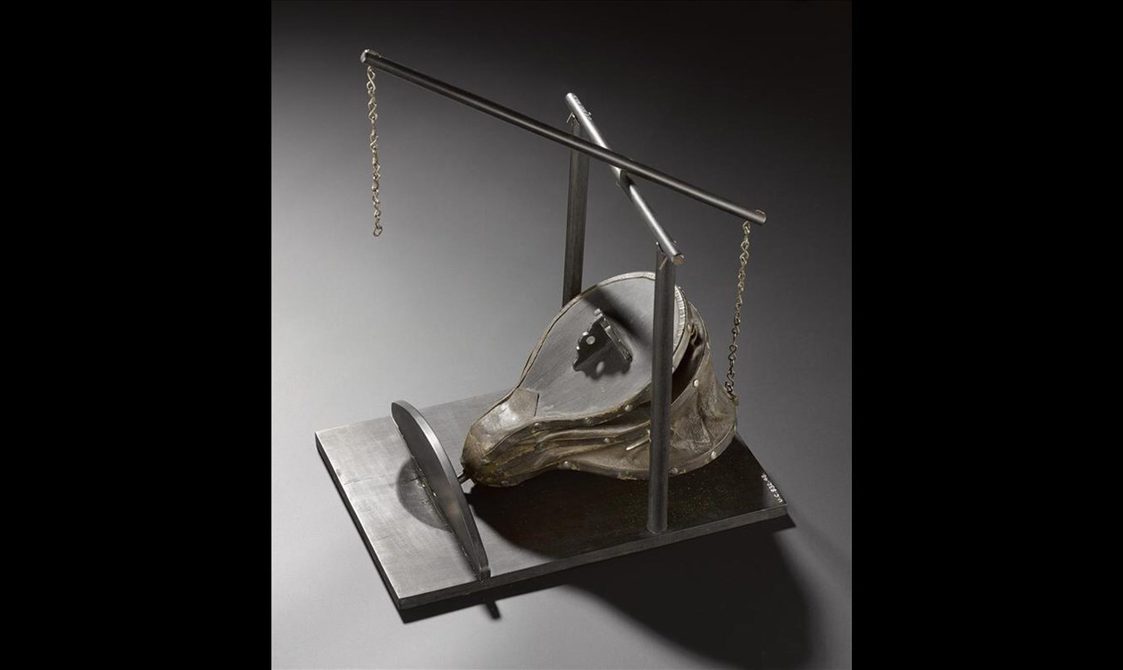

In particular, Margaret Tytler’s model of Indian bellows and its label caught everyone’s attention. The label was written by a previous group of Networking Key Services who supported people of South Asian origin during a previous collaboration with National Museums Scotland. This discovery prompted the group to research and write more about Margaret Tytler and her links with India via her work for the South Asian Stories project.

Image gallery

Model of a blacksmith’s bellows introduced by the British, made to a scale of 3 inches to 1 foot, ebony, stained wood, leather, metal, India, Bihar, Patna, 1815-21. Museum reference A.UC.832.48.

Model of an apparatus for making butter, made to a scale of 2 inches to 1 foot, ebony, stained wood, ceramic, cane, India, Bihar, Patna or Tirhut, 1815-21. Museum reference A.UC.832.17.

Model of a loom for weaving woollen carpets, made to a scale of 2 inches to 1 foot, ebony, stained wood, fibre, wool, metal, India, Bihar, Patna, 1815-21. Museum reference A.UC.832.45.

Model showing oxen treading out corn, made to a scale of 2/5 of an inch to 1 foot, stained wood, ebony, fibre, India, Bihar, Patna and Tirhut, 1815-21. Museum reference A.UC.832.11.

Acknowledging the skills and industry of 19th century India in Scotland

While in India, Margaret lived in Patna, Bihar and later in Tirhut where she worked on producing more than 80 models of Indian agricultural and other manufacturing tools that played a hugely significant role in different production processes. She perceived these tools as part of the innovative production processes, and felt that the ideas could be taken to Scotland as a learning for the development of economy.

Although she requested in her will that the models should be passed on to the University of Edinburgh as a learning and comparitive studies tool, her collection in London was displayed more as ethnography learning rather than tools for the development of agriculture and manufacturing. Her interest in the culture and lifestyle of people in India was a major highlight. No doubt, while there she was inspired by the culture and lifestyle and manufacturing techniques in India, and commissioned models of unique Indian manufacturing tools to illustrate the art and manufacture of India. Yet, her vision was to bring learning from other cultures’ production processes and technologies to benefit productivity in Britain.

The models produced range from Indian bellows, a saw, oil mill, weaving looms and blacksmith tools, to models of tools for churning butter and making ropes. The models, indeed, demonstrate the local technology for production purposes. She needs to be applauded for recognising the unique and progressive manufacturing techniques and skills of local artisans in India.

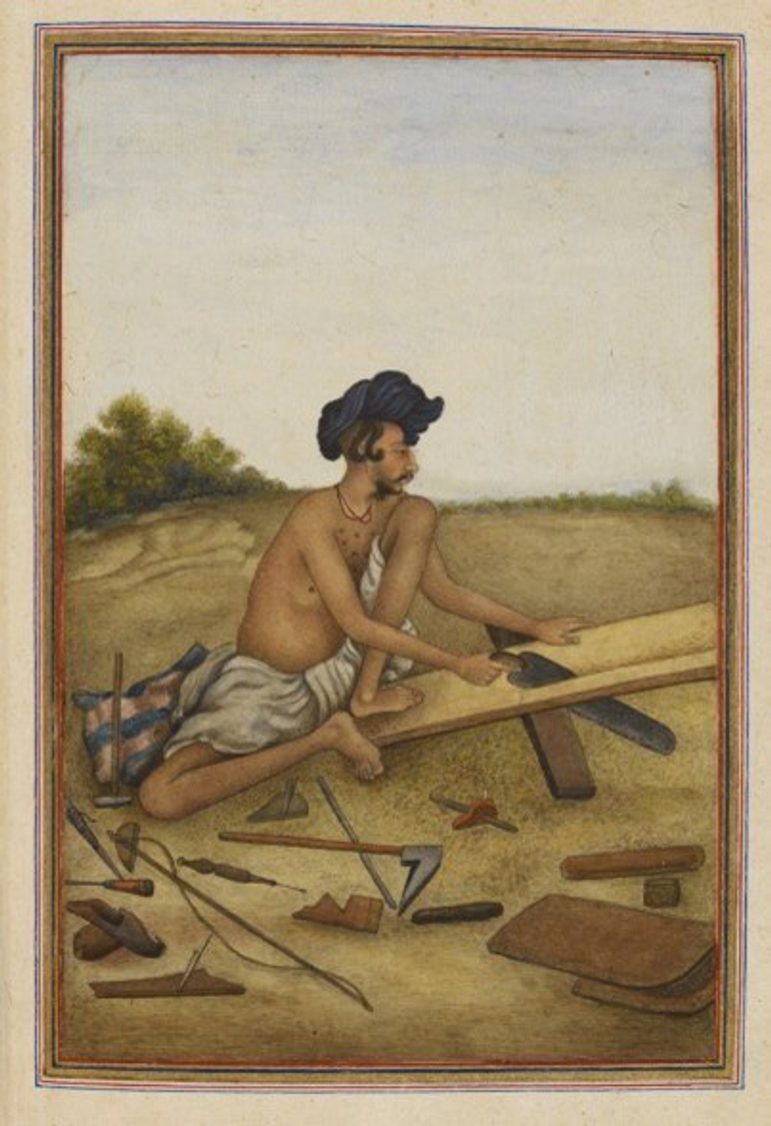

However, it’s important to give a thought and huge credit to the local artisans who helped make these models. Though Margaret Tytler’s interest in science and mathematics ensured the precision of the models, the highly commendable skills of local artisans have made a huge contribution in making the project successful.

Indian craftsman at work, north India, early 19th century.

Local artisans in the 18th and 19th centuries belonged to the working class and did not receive much importance in society and their skills were not appreciated. Nevertheless, living in the 21st century where human rights are of paramount importance globally, it’s never too late to give a standing ovation to these artisans who created these beautiful models under the guidance of Margaret Tytler.

A selection of models can be found in the Collecting Stories gallery at the National Museum of Scotland.

Written by

Members of the Networking Key Services group

In 2022 South Asian community groups supported by Networking Key Services (NKS) visited the National Museum of Scotland to view the galleries and interpret objects from the South Asian and Scottish collections.