Uniquely Scottish: 5 highlights of the silver collections

News Story

Scottish craftsmen in the Renaissance and Early Modern periods (c.1450-1750) produced a wealth of silver artefacts. Although their work was largely influenced by contemporary British and European fashions, the country’s silversmiths also created designs that were unique to Scotland.

Some of the objects survive in prolific number and are instantly recognisable. Many are still used today as national icons. Others are among the earliest and rarest survivals of the Scottish silversmiths’ craft.

Lyndsay McGill, Curator of Renaissance and Early Modern History, explores five highlights from the Museum's silver collection.

1. Mazers

Mazers are communal drinking vessels that were popular during the second half of the sixteenth century. Traditionally, they were made of a wooden bowl, usually maple, with an applied silver rim.

In Scotland there was demand for the mazer bowl to be mounted on a silver or silver-gilt stem several inches high. While England and Europe continued to favour those without a stem, the ‘standing mazer’ became a speciality of Scotland. Today, only nine Scottish mazers are known to survive and of those, seven have stems.

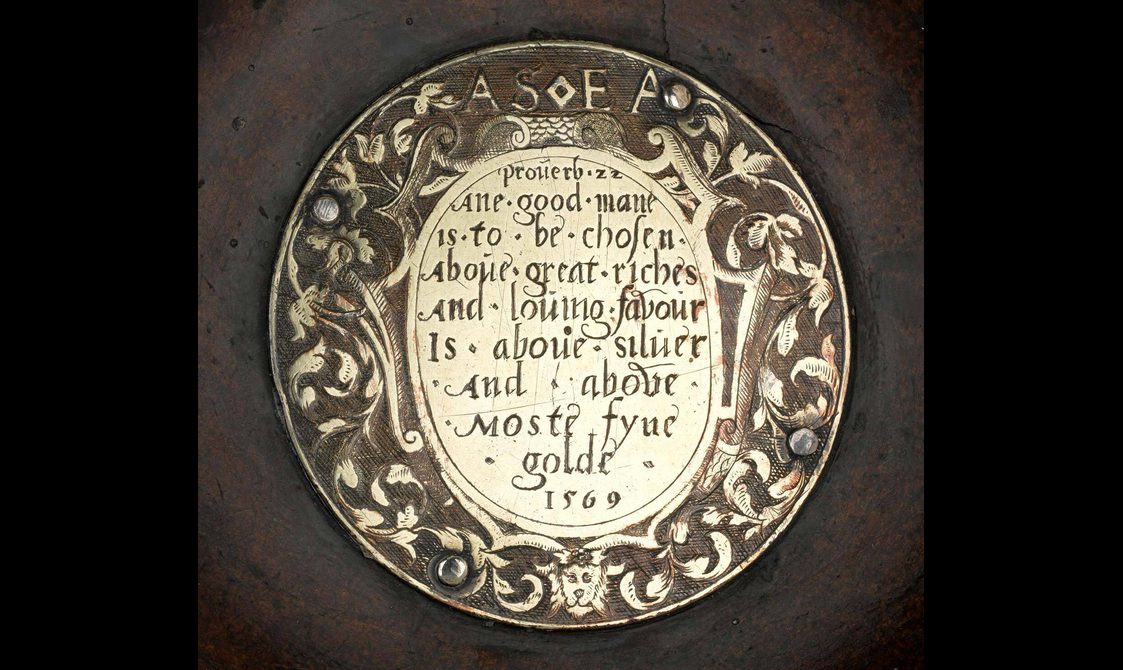

The Galloway mazer is one of the finest surviving mazers. It was made by James Gray, a silversmith working in the Canongate (now part of Edinburgh). There are engraved arms on the rim together with the initials ‘AS EA’. These represent Archibald Stewart and Ellen Acheson who married in 1569, the year the mazer was created. The cup was probably commissioned to celebrate their marriage. In the same year, Stewart was also admitted as a burgess of the town. Ten years later he became the Lord Provost of Edinburgh. Through his nephew, his family went on to inherit the Earldom of Galloway.

Image gallery

2. Quaichs

Quaichs are quintessential Scottish drinking vessels. The name comes from the Gaelic cuach, meaning 'cup'. Originally produced in wood, they were often built in sections or staves. They were then bound with withies (strips of willow) with the handles carved as an extension of the stave, or they were simply turned on a lathe.

During the mid-17th century, silversmiths turned their skills towards the wooden quaich. They began adding silver mounts in the form of rims, feet, and fitted plates to the tops of the handles or the centre of the bowl. By the 1660s, silversmiths were making quaichs entirely of silver.

Significantly, they continued to produce them in the same style as the traditional wooden ones. They imitated the joins of the staves and the withies by engraving the silver. They also replicated the box-like handles, or lugs, and stayed away from flat handles like those seen on British and Continental wine tasters.

The shallow bowl raised on a foot rim and thick downward turning or flared lugs is different to other vessels. So while national drinking vessels exist in other countries, the quaich is a uniquely Scottish phenomenon.

Image gallery

Quaich by Matthew Colquhoun, Ayr c.1685. Museum reference K.2005.345.

Wooden staved quaich with silver mounts possibly by Alexander Fraser, Inverness, c.1680. Museum reference K.2006.434.

3. Thistle cups

Thistle cups existed for a relatively short time. They date from approximately the 1680s to 1720s. They take their name from their thistle shape which is an inverted bell-shaped body with a flared lip, together with raised lobed decorations on the lower part of the cup. These features are believed to be reminiscent of a thistle-head. All these components together make a distinctly Scottish form of cup. The name is a later invention, used by dealers and collectors as a way of identifying them.

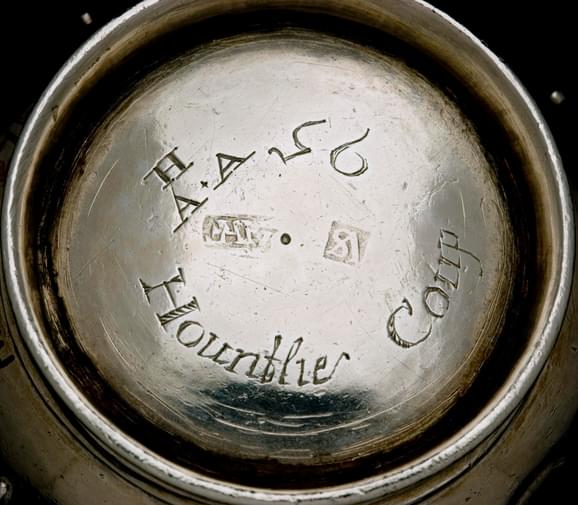

There is evidence that these cups were highly thought of. This cup was used as a horse racing price in 1695 as indicated by the engraving on its base which says 'Hountlie Coup / 95’. The Huntly Races in Aberdeenshire were horse racing events held once a year in September from 1695 to 1749 which coincided with the local fair. The Scottish Parliament granted that the fair be called ‘Charles Fair’ in honour of the deceased Charles II. The landowner, George the 1st Duke of Gordon, followed by his son Alexander the 2nd Duke, were Catholics. They continued to support the exiled House of Stuart and the races became an occasion where Jacobite supporters could meet covertly.

The engraving at the inner base of the Huntly Race thistle cup. Note also the faint assay mark at the centre.

The Huntly Race thistle cup, by William Scott II, Banff, 1695. Museum reference H.1996.275.

4. Ovoid urns

The creation of these wonderful ovoid urns occurred during the 18th century. Luxury beverages, such as tea, coffee, and hot chocolate, were becoming sought after drinks. As the demand for these grew, so did the work of the silversmith. People required new equipment like hot water kettles, spoon trays, milk jugs, and sugar bowls.

These urns have been a source of debate with some suggesting that they were teapots. However, there are now more convincing arguments for them being used for coffee. The spouts are strategically placed a little up the body which would allow coffee grounds to settle in the base and the liquid to be drawn off without disturbing the sediment. In addition, there are records of very large coffee pots being produced.

This coffee pot is mentioned in the account ledger of the maker John Rollo. It states that in December 1735 'The Honble Andrew Wauchope of Niddrie Esq' paid ‘£23.5.8' for 'one Coffe poot 62 ozn 2dr’ and that he paid ‘To Duty £1 11s’ and ‘12s’ for 'Ingraving round the mouth'.

Today this coffee pot weighs 61.11oz, which is less than the original 62oz and 2 drops. The discrepancy in weight can be accounted for the normal loss of silver which occurs over centuries of polishing.

To date, we know of only seventeen examples of ovoid coffee pots. All have Edinburgh hallmarks except one from Dundee. These surviving coffee pots date from 1719 to 1768.

Ovoid urn by John Rollo, Edinburgh, 1735-36. Museum reference K.2009.3.

5. Heart brooches

Heart brooches have existed in Scotland since at least the medieval period. While they are not unique to Scotland, they have become deeply associated with this country. They appear to have been a popular form of jewellery, indicated by the large number that survive.

While variations of the heart brooch exist, it can be argued that certain design features are classically Scottish. Certain features that were popular with the Inverness silversmiths became common across Scotland. This includes a crown, which was stylised as either a ‘bird-head’, ‘spectacle’ or ‘flared’ design. Small projections at the shoulders and near the base feature, as well as a chevron-style bar within the lower portion of the heart. Clasically Scottish heart brooches also tend to have a a three-lobed tip at the bottom.

Heart brooches in Scotland are often referred to as ‘luckenbooths’. The word refers to the locked booths or shops that formed the goldsmithing and jewellery quarter in Edinburgh’s Old Town. These were next to St Giles Kirk, and it is believed that many of these brooches were made here. However, it can be argued that Inverness and Aberdeen produced more heart brooches during the 18th and 19th centuries than Edinburgh. In 1817 the Edinburgh luckenbooths were torn down to widen the High Street. No heart brooches were produced in these shops after that date.

Indeed, the name ’luckenbooth’ was not known to have existed prior to the late 19th century. It may have been created by Victorian antiquarians and collectors as part of their growing classification of historical objects. Or sellers might have concocted the name as a powerful marketing tool, using heritage as part of their sales pitch.

Image gallery

Heart brooch, gold, 18th century. An inscription on the other side reads, ‘WRONG NOT THE ♥ WHOS JOY THOU ART’. Museum reference H.NGA 73.

Heart brooch showing typical Scottish features by Inverness maker Daniel Ferguson c. 1862

Single Heart Shaped, Gold Brooch Surmounted By A Crown Of Birds' Heads, By Alexander Stewart, Inverness, C. 1796 1800. Museum reference H.1991.2.