Key in a search term below to search our website.

Key in a search term below to search our website.

Discover how an extra-terrestrial exhibit was made ready for display in the National Museum of Scotland.

Date

Approx. 800,000 years old

Found

2004 at Muonionalusta (north east of Kitkiojarvi), Pajala Kommun, Norrbotten, Sweden

Made from

Metal, 91.5% iron and 8.5% nickel

Weight

170kg

Museum reference

On display

Earth in Space, Level 1, National Museum of Scotland

Did you know

The Muonionalusta meteorite is highly magnetic.

When you engage with an exhibit in a museum, you learn where it’s from and the part it plays in history, culture or nature. It may link in with other exhibits to tell a more wide-ranging story. But often the story of the object’s journey before its inclusion in the museum is equally fascinating.

As Peter Davidson, Curator of Mineralogy explains:

“Our Earth in Space gallery will explore the origins and growth of the Universe and the place of the Earth through exciting static and interactive displays on subjects such as ‘matter’, ‘space’ and the ‘origins of life’. We will use meteorites to show that matter from Space is the same as matter on Earth. We wanted to find a large meteorite which could go on open display so that visitors can touch a real extra-terrestrial object, feeling both the strangeness and familiarity of these rocks from space.”

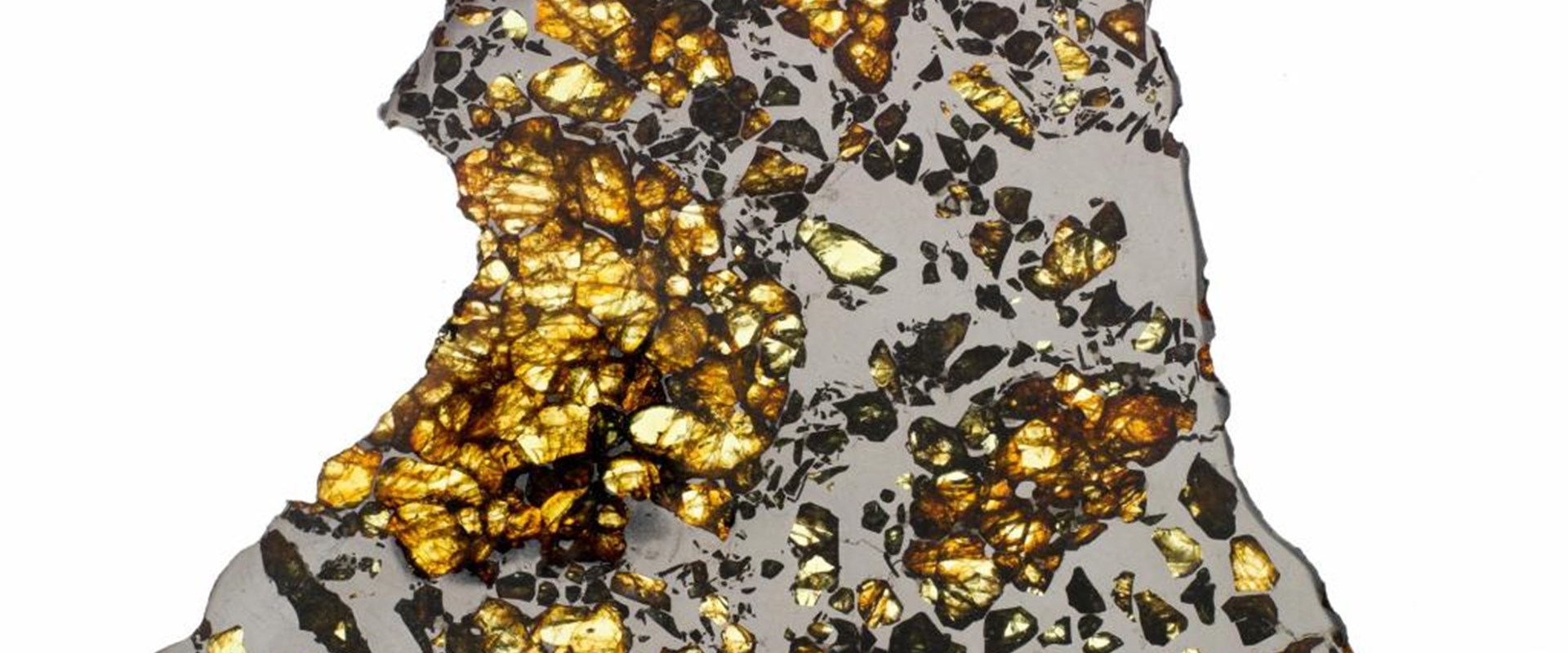

And so a fragment of the Muonionalusta meteorite was collected from a dealer in Denmark. It takes its name from the parish around the village of Kitkiojöki in northern Sweden, where a number of large meteorite fragments have been found since 1906. This piece was uncovered in 2004 and weighs a hefty 170kg. It was part of a much larger meteor which broke up as it entered the Earth’s atmosphere about 800,000 years ago.

Earth in Space tells the story of the three main meteorite types: irons, stony-irons and stony. The names reflect their compositions: mainly metal for irons, principally rock for stony meteorites and a mixture of the two for stony-irons. The Muonionalusta meteorite is an example from the iron group.

Iron meteorites are thought to have formed at the core of a small planet or large asteroid and may be similar to the material at the core of the Earth. Staff at the National Museums Collection Centre found the meteorite to be highly corroded and their primary concern was to halt the corrosion before too much damage was done. They placed it in a protective polythene enclosure with dry silica gel. However, corrosion continued to develop so it was agreed there was a need for a specific project between the Natural Sciences curators (Peter Davidson and Vicen Carrio) and the Conservation and Analytical Research Department (Theo Skinner, Jane Clark, Lore Troalen and a student from Paris Sorbonne University, Gaëlle Giralt).

It’s very common for archaeological iron artefacts buried in soil or found underwater to suffer from active corrosion. Treatments to stop such corrosion have been studied extensively. However there has been less research carried out into the corrosion of meteorites and what has been done relates to smaller scale specimens. Fortunately the conservation workshop at the Collection Centre had the capability to deal with large-scale object conservation.

The question remained: which stabilisation treatment to use? Jane Clark, Artefact Conservator explains:

"We decided on alkaline sulphite treatment because of its proven efficiency and affordability. The meteorite was then immersed for several months into a treatment bath."

Lore Troalen, Analytical Scientist, continues the story, saying:

"In order to understand the nature of the corrosion, flakes of corroded metal from the meteorite surface have been scientifically investigated by means of elemental and structural analysis. This is helping to assess the efficiency of the stabilisation treatment and to decide on the final display plans for the conserved meteorite so that it can star for many years to come as the only out-of-this world hands-on display in the National Museum of Scotland."

The Muonionalusta meteorite really has two stories to tell: one about meteorites and the other about the skill of the geologists, scientists and conservators who worked together to prepare it for its first public appearance.