Object handling

This training sets out our guidelines and best practice for handling museum collections.

| This training is for | Level | Length | How to complete the training |

|---|---|---|---|

| People working with museum collections | Beginner | 1-2hrs (approx) | Follow the sections below in order, read the added resources, watch the videos and then move onto Object Packing |

When and why do we handle collections?

Objects are at the highest risk of damage when they are being handled or moved.

Wherever possible, limit the extent and frequency of handling and moving objects. For example, if an examination of a collection or object is required, conduct it in the store and examine the object in situ.

Try to combine multiple consultations, or consider digitising the object or creating a facsimile.

When you do need to move an object (ie, you're creating an exhibition, photographing the collection or moving an object to improve storage), safe handling and moving is necessary.

Why is good practice important?

Objects are fragile for many reasons: owing to their age, their past use or even their manufacture.

They are also often the only surviving examples of their kind and it is the role of the museum to preserve these objects for as long as possible.

Good object handling practices should be applied to all objects in a museum's collection to minimise the risk of damage during consultation, moving and handling.

Damage

Damage can be divided into two categories:

- accidental damage which is visible immediately such as tears, breaks and bends, and;

- cumulative damage which develops over time, such as corrosion, fracturing and accumulation of dirt.

Damage often occurs in areas of objects that are weak. However, not all weak areas are immediately visible.

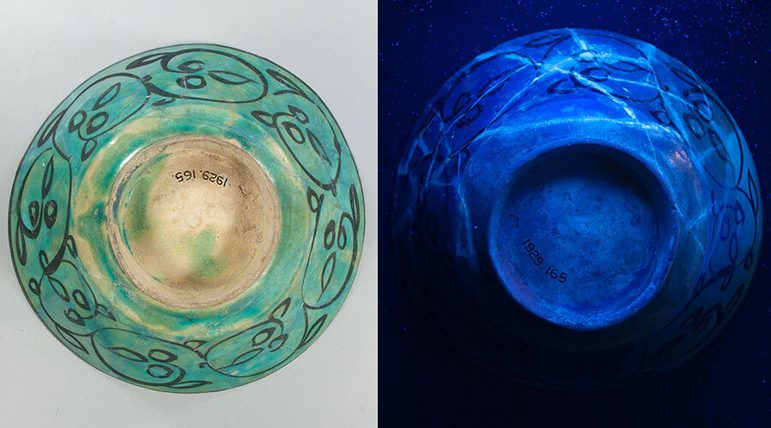

For example, apart from some crazing to the glaze, the green ceramic in the image looks relatively intact. However, placed under UV light the historic adhesive fluoresces, illuminating old repairs and making visible areas of vulnerability in the ceramics.

Preparation

Preparation for handling and moving an object or collection is crucial as it mitigates the risks of moves going awry and causing damage to objects. Accidents often happen when collections are being moved in a hurry or to an unfamiliar location.

When moving objects in any setting there are six key elements that should be considered in advance:

1. Destination Where is the object going? Is there a suitable space clear to set the object down? Do you need to add protection to the surface to cushion the object? If the object is to be set on the floor, have you got suitable equipment to do so?

2. Route What is the best route to take the object? (Remember, the shortest may not be the best). Do you have assistance to open doors? Are all potential obstacles cleared away?

3. Timing How long will this move take? Are you aware of all restrictive scheduling (for example, when does the building close, are any fire drills planned)? Do you have a contingency plan if the move overruns?

4. Equipment Do you have the correct equipment for the job? How heavy is the object – can you and/or the equipment you intend to use safely lift the object?

5. Object Have you inspected the object(s) prior to the move? Are you aware of its condition? Have you consulted all relevant documentation for advice of weaknesses or hazards present?

6. You Have you removed all jewellery or lanyards that might get caught on, scratch or damage the object? Do you have the right gloves? Do you need Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)?

Gloves

The right gloves protect objects from dirt and oils from your skin, where they can cause damage. They also protect you from poisons and hazards which are present on some collections.

Powder-free nitrile gloves are the most suitable for working with collections. However, all gloves will limit your dexterity, so a good fit is essential. Heavy-duty work gloves with nitrile coatings are appropriate for use with more robust objects where the object’s surface is rougher and may snag or split disposable nitrile gloves.

It is not recommended that cotton gloves be used when handling collections as they do not provide a complete barrier between your skin and the object.

It is also common for the fibres to get caught and snag where they come into contact with the surface of collections.

While the use of disposable nitrile gloves increase waste there are glove recycling schemes available to reduce environmental impact.

Image gallery

Guidance for handling objects by material

We've created the guide below detailing the measures you should consider when handling these common materials. However, this guide should be used as a minimum standard of handling collections: all objects should be considered individually, and specialist advice sought if the object appears particularly fragile or not as expected.

Click to expand each section below:

Ceramics and glass

Preparation

When handling ceramics and glass, first check for existing fractures and damage as these will indicate the especially weak and fragile areas of the object. Ensure your work surface is padded either with a piece of plastazote, or a layer of bubble wrap/jiffy foam under a sheet of acid-free tissue paper.

It is important to wear gloves especially with non-glazed ceramics as their porous surface is particularly susceptible to oils and dirt from your skin. Wearing gloves with glazed and glass objects also limits the need for additional surface cleaning which could eventually cause cumulative damage to the object.

How to handle

When lifting and handling ceramics and glass, cradle even the smallest object with two hands. Remove any loose parts (most commonly lids) and treat them as a separate object.

Beware

Do not lift by handles, knobs and rims as these are areas of weakness – weaknesses caused by the manufacturing process or cumulative damage whilst the object was in use.

Crizzled glass will shatter with only a light tap, so be extra careful when setting down on a surface.

Metals

Preparation

Always wear gloves when handling metals as oils from your skin can promote rapid tarnishing. It is important also to change gloves when handling different metals as microscopic particles can be transferred from one metal to the other and will also increase the tarnishing rate.

How to handle

When handling metal objects, be aware they can often be more vulnerable than they appear. For example, tin and lead are particularly soft metals and are susceptible to denting and scratches. In addition, be aware of soldered joints and decoration which are often innate weaknesses in the structure of the object.

Textiles

Textiles can be more fragile than they appear. They can become brittle and faded with age, particularly those that have been subject to prolonged exposure to light. Silk is particularly vulnerable, in part due to the common use of weighting agents in manufacture. Over time these various agents weaken the silk fibres making them susceptible to splitting along folds and during handling.

Preparation

Generally, it is not advised that gloves are necessary during handling. Clean hands with the improved dexterity offered by not wearing gloves is often the preferred practice. The common exception to this is textiles with metal thread or detailing, here gloves are necessary to protect the metals from corrosion.

Textiles can be more fragile than they appear. Textiles can become brittle and faded with age, particularly those that have been subject to prolonged exposure to light. Silk is particularly vulnerable, in part due to the common use of weighting agents in manufacture. Over time these various agents weaken the silk fibres making them susceptible to splitting along folds and during handling.

Handling guidance

When handling textiles, always assess the object for fastenings, beadings and sequins which can catch on textiles creating pulls and damage. Avoid such damage with good, careful handling and by maintaining an awareness of where these points of risk are. Where required, you can wrap such fastenings and beadings in acid-free tissue to protect the fabric from anything which may catch.

If the textile is particularly large or long, you may need to carry it over both arms to provide adequate support. If you are doing this, make sure you don’t have any buttons or decorations on your own clothes that may catch or snag the textile. Alternatively, use two people to handle the textile.

Handling stored textiles

Some textile garments are suitable to be stored on padded hangers, particularly those from the twentieth century. Where garments are stored like this is possible to handle them whilst on their hanger: lift from rail by the hanger hook (not the shoulder where the garment is sitting); and carry by the hook; if necessary, draping over an arm to ensure the garment does not drag on the floor.

Older, more fragile textiles are often stored boxed and are suitable to be moved in their box. See the Object Packing guidance for more information on how to pack textiles in boxes.

Flat textiles, such as tapestries, are often stored rolled on acid-free cardboard tubes, again they can be moved on their roll. The move will require a person at either end of the roll: either a pole can be pushed through the middle of the tube or it can be lifted from the end of the tube itself (be careful to ensure there is exposed tube at the end of the roll and you will not be touching the textile itself).

Furniture

Preparation

As one of the bulkier and heavier types of museum collections, furniture is often difficult to handle and move, and is therefore more at risk of damage.

Be aware of old repairs and weak joints as well as structural weakness caused by historic infestations of furniture beetle.

Handling guidance

When handling and moving furniture, consider how it is assembled. Check if the object is designed to separate into pieces, as many large cabinets and dressers often do. Although be sure of this, as a misguided attempt to separate parts may result in fixings or dowels getting damaged.

When lifting furniture, lift from the lowest load bearing point. This is often the legs or the rails supporting the seat of the chair or top of a table. Inspect the object first to consider which parts seem structurally stable and resilient to handling. Do not lift by handles or by ornate fixtures as they have not been designed to bear the weight of the object. When inspecting inside drawers and cupboards it is advisable to limit the use of handles and knobs, lifting out and supporting draws and cupboard doors by the body where possible.

When moving items of furniture and wood, secure moving parts like doors with unbleached cotton tape to stop them swinging open during the move. Padding corners beforehand will also limit damage caused by any accidental bumps. Consider moving the object on a pallet or other device to limit reliance on personal strength during the move.

Beware

Gilding and upholstery are particularly prone to damage and should be touched as little as possible. Synthetic twentieth-century upholstery foam is particularly prone to degradation. Because of this, it is best to avoid placing pressure on upholstery in order to avoid the object become misshapen.

Frames

Handling guidance

Lift frames vertically, particularly if they are glazed. This not only makes them easier to manoeuvre but limits the risk that they will collapse from their own weight.

You should also carry frames from below as lifting from above will put excess strain on joints.

Always use enough people to safely lift the object – often two people are required with a third to assist with manoeuvering and setting the object down.

Paper and photographs

Preparation

Like textiles, it is not imperative to wear gloves when handling paper as the improved dexterity afforded by not wearing gloves is more advantageous.

However, it is necessary to wear gloves when handling photographs due to the chemical make-up of the photographic layer and on some shiny or waxed papers which can be susceptible fingerprints.

Handling guidance

When handling these objects do not touch the image, be it pencil, chalk, paint or photographic, as these are particularly susceptible to damage – especially that of a cumulative nature.

Pick-up by the edges and support on acid-free card wherever possible to limit direct handling. If an item is rolled, do not attempt to unfurl it unless absolutely necessary and consult a paper conservator if you have any doubts about the objects fragility and suitability to being unfurled.

Stone

Stone objects can look robust but are particularly susceptible to damage and chipping when being moved and lowered.

Preparation

Like with any material, stone objects vary hugely in size. Treat small objects like you would ceramics and glass. Treat larger items with similar care: pad around edges and use lifting equipment to limit the risk of damage from poor manual handling.

Handling guidance

Where flat stone objects are being carried and not being laid flat on a surface for moving, ensure they are being carried vertically (like frames, above) as they can break under their own weight.

Bone and ivory

Preparation

Wear nitrile gloves to prevent finger marks and sweat deposition. These materials are easily chipped so they should be packed or protected when you are moving them, placed on a padded surface for storage or consultation.

Humidity

These materials are particularly vulnerable to changes in relative humidity. Wearing gloves will protect from localised changes in relative humidity (heat and moisture from the hands are sufficient to warp thin ivory). Ivory is a hygroscopic material: it absorbs or releases moisture with changing humidity, swelling or shrinking in response to variations in moisture content. Fluctuations in RH can cause cracking and warping. Ivory is also easily stained and must not be left in contact with iron, copper, brass or coloured materials.

Leather

Preparation

Always wear gloves when handling leather as it is particularly susceptible to mould and your hands will provide the micro-organisms to initiate mould growth. Leather can become brittle with age so always exercise caution.

Beware

If leather has lost its flexibility do not be tempted to try and bend it back into shape - consult a conservator for advice. You must also be careful of the object’s surface as leather is often soft and easily scratched. Be careful of any decoration and avoid touching gilding wherever possible.

Handling guidance

When consulting leather bound books never put your finger over the top of the spine and pull; you may break the spine and the headband. If there is space, put your hand right in and push the book out from behind. If there is no space, push two of the books on either side of the book you want, further into the shelf and then grip the book lightly between thumb and fingers around its spine and draw out.

Always grip the book firmly with your fingers completely around the spine. Never pack books away tightly as this may damage the spines.

Accidental damage

Accidents happen, and objects get damaged. If you find, or are party to collections damage, it is important to take measures to stop further damage. Follow your institution's processes for reporting and managing damage and if you are collecting the damaged object, undertake the following steps.

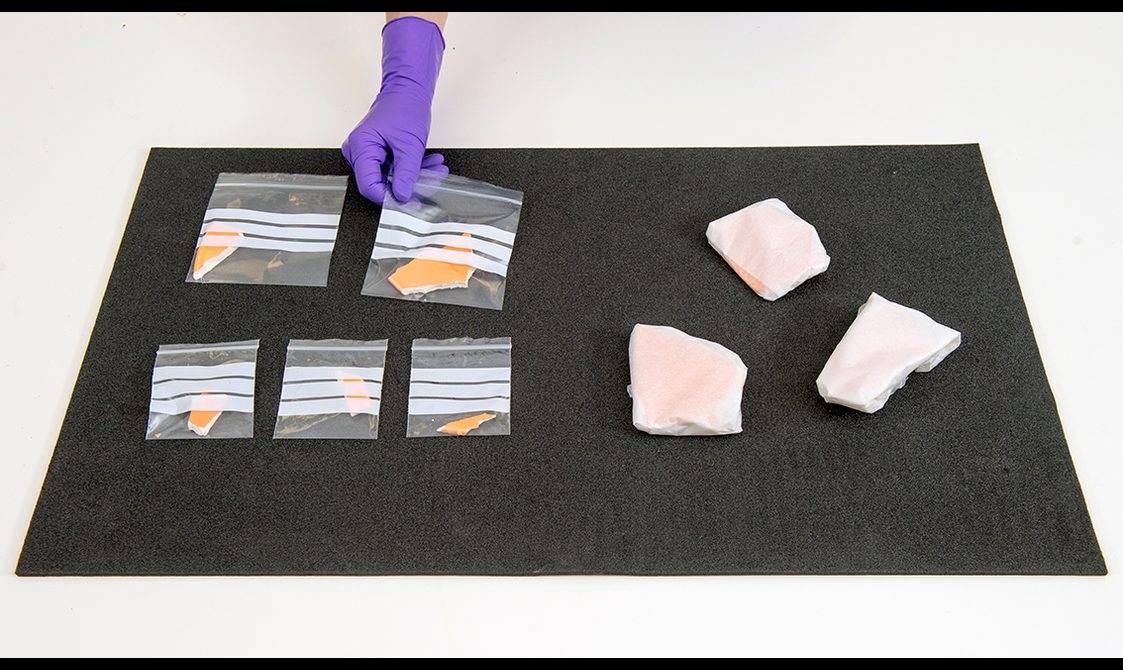

- Cordon off the area.

- Take detailed photos of the object in situ, including any fragments and how they are positioned.

- Collect the largest pieces, being careful to assess for areas of weakness that could become further damage.

- Pack these pieces into a container individually, do not attempt to piece them back together.

- Collect or sweep up smaller fragments and put them in polythene bags.

- Label all bags and containers with the object number and number of parts/receptacles it is now divided into.

Image gallery

Health & safety

Hazards

Hazards are common in museum and can pose a severe risk to health. Below is a list of hazards frequently encountered in National Museums Scotland collections and examples of where they can be found:

- Radiation: found in many of our aircraft instruments, certain geological specimens, and even glass where it has been coloured with a radioactive substance.

- Poisons: mercury is found in barometers and thermometers and was used in mirror manufacture until the 1900s; arsenic was historically used as a dye; many weapons in our world cultures collections have been treated with poisons while in use. Substances such as mercury and arsenic were historically used to treat pest infestations of taxidermy and natural history collections.

- Asbestos: legal to use until 2000, asbestos was used extensively until then. It is most common in - but not exclusive to - our 20th century technology collection. Asbestos dust is the most dangerous, and if inhaled can cause severe health problems.

Gloves and face masks can offer basic protection but offer no protection against radiation and asbestos. Always consult object records for warnings of hazards but be aware they may not have yet been identified. Exercise caution, and if hazards are suspected cease work, consult a specialist, implement and follow risk assessments.

An excellent online training module on hazards in museum collections is available free from the Museum of London.

Manual handling

The handling and movement of large and heavy objects in museum collections requires the implementation of good manual handling practices.

Ensure that the correct Personal Protective Equipment is used, for example safety shoes and heavy-duty gloves.

It is also important to recognise that manual handling limits judgement as your mind is focused on lifting and balancing the load and less so on your surroundings. It is for this reason it is important to have a method statement (like the sample below) and clear plan for the move to ensure all those understand the move before it begins.

Download

Handling guidance

Lift frames vertically, particularly if they are glazed. This not only makes them easier to manoeuvre but limits the risk that they will collapse from their own weight.

You should also carry frames from below as lifting from above will put excess strain on joints.

Always use enough people to safely lift the object – often two people are required with a third to assist with manoeuvering and setting the object down.

The Manual Handling regulations set a maximum load of between 16.5 and 25kg for loads at elbow height.

However, you must reduce these loads by 5kg when carrying in any other position and by 10kg when objects are being carried below elbow height.

Wherever possible use equipment to limit the manual handling required, such as skates, lifting tables, pallet trucks and forklifts. Consider bringing in specialists if the move is particularly large or complex.

This video from the British Museum demonstrates how lifting equipment can be used to move a heavy object and limit manual handling.

Summary

To summarise, when moving an object or collection, make sure you:

- Identify the material or object type(s) you will be dealing with, and

- Consider the six preparation factors in relation to each. It is not uncommon to combine handling techniques as museum collections can vary extensively in composition.

- Think outside the box when considering how to handle and move collections. For example, the use of a mortuary table has been identified as the safest and most efficient way to move our collection of historic coffins.

Further training resources

Object packing

After good handling practices, the next most important skill to apply to consulting and moving collections is good packing. This training sets out our guidelines for the best methods and materials for packing objects.

Object labelling

This training sets out our best practice guidelines for labelling objects in museum collections.

Integrated pest management

This training sets out our guidelines and best practice for integrated pest management.